The former propaganda artist for the DPRK regime now lives in South Korea, after swimming to freedom in the 1990s.

North Korean defector artist Sun Mu’s debut U.S. museum exhibition fixes its axis on lost utopias in halcyon landscapes of childhood and Korean unification. In the 2012 oil painting We Together, on view at Culver City’s Wende Museum, children from the two Koreas run gleefully through a meadow dotted with purple stalks of grass. Another composition shows a boy and girl dressed in as cosmonauts, joined together in a hula hoop.

“If you look at it, this kid is from South Korea, this one is from North Korea,” he tells me. “These children are supposed to have fun together, but they can’t because the country is divided.”

A banner of text cuts through the bottom of the image as in compositions of DPRK propaganda posters and translates to “We want peace,” also the title of the painting. North Korean propaganda posters share the theme of unification, but speak in the triumphalist language of nationalism, while Sun Mu’s compositions are apolitical and focused on the personal realm. A DPRK poster that similarly features a hula hoop functions as political call to action (in this case, “running toward a strong unified country.”)

A bit of Stalinist kitsch: by taking up characteristic tropes of the poster tradition of his homeland, Sun Mu incidentally borrows outfits from the Russians, the cosmonauts’ uniforms an accidental-seeming visual referent to Soviet visions of early space exploration.

The buoyant and sentimental compositions of unification as experienced by children are detailed with care and painted in expressive, saccharine, tones—in stark contrast with the bright bands of red and black the artist uses to capture the intensity of DPRK children and North Korean culture of conformity.

The fascistic salute of uniformed pioneer children in Scenery (2010) is perhaps the most unsettling of these images. Initially, its subjects appear identical or even a single figure reproduced across a canvas. However, as you linger on the figures, tiny variations in their expressions, the shapes of their ties and open mouths become just discernible enough to conjure the eerie specter of a choreographer.

“When I was in North Korea, I was happy as it was,” Sun Mu says of his time as a propaganda artist for the regime. “But now that I’m outside of North Korea, I realize that I actually used these children I was drawing back then as propaganda.”

“I want to keep drawing children, but promoting my own propaganda,” he adds. The artist defines his work as an expression of freedom, and insists that its interpretation is left open to the viewer, a rejection of the DPRK art institution’s central tenet of art being evaluated in terms of its ability to capture objective beauty and transmit an ideological message.

“He is deeply convinced that his artwork has a purpose,” says North Korean art scholar Koen de Ceuster. “Art should not be frivolous, nor simply aesthetic; art has something to say, to add. But what it has to say is for the viewer to pick up.”

The ambiguity of much of the work and its contentious subject matter have garnered controversy both for being too critical of the DPRK and for being insufficiently critical, as the Washington Post points out. The paintings featured in the Wende show were retrieved from China, where they were seized by authorities, a scene depicted in the closing minutes of the 2015 Netflix documentary “I Am Sun Mu.”

This has also been the case in South Korea, where the artist relocated after his defection during the famines of the 1990s by swimming across the Tumen river to China.

“Before I came to South Korea, I thought that it was a country that has no ties to ideology, a country that is really free,” he says. “But when I gave my first exhibition on North Korea I almost got arrested by the police, and so that’s when I realized that we didn’t know each other. I just had this idea of South Korea that was free of ideology.”

Part of what makes Sun Mu’s art engaging is that it is not dogmatic—in particular, it is not a monolithic criticism of the DPRK. The aesthetic marks of the repressive state also force us to confront the uncomfortable allure of the totalitarian seduction.

“His work is often not crudely anti-North Korea, but rather much more nuanced and multi-layered, where he plays with the appeal of the sugar candy primal colors and the upbeat emotions,” says de Ceuster. “But on closer scrutiny, something is amiss and under the apparent ‘happy shiny people’ something deeply uncomfortable lingers.”

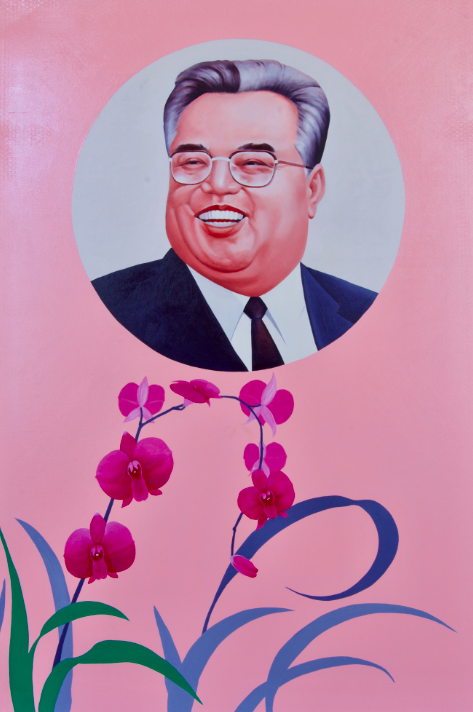

Sun Mu’s work has been widely compared to pop art, and his paintings often satirize the personality cult of the Kim family by placing them in close contact with iconography of consumerism.

“In the United States, they have their own propaganda, just like South Korea has their own propaganda,” he tells me, later noting Trump’s use of defector Ji Seong-Ho as a political prop in his January 2018 State of the Union address. “I want to believe that Trump wants to bring peace in Korean Peninsula,” he says with no intonation of snark. “However, I mostly thought he was using propaganda through [sic] him.”

As Kim Jong-Il once proclaimed, “abstractness in art is death,” the North Korean state is deeply vested in cultivating artists and training them in the tradition of socialist realism and techniques that capture a vision of objective beauty as construed by the ultra nationalist regime and promote its philosophy of Juche (self determination). The more familiar examples of art produced by the regime, its cinema and Arirang Games performance, follow this model.

Wende chief curator curator Joes Segal, too, draws comparisons with the USSR.

“If you look at the role of art in the Western world and under communism, art in the Soviet Union was never meant as decoration,” says Segal. “Is a kind of impulse to make you a better human being, and that could be very horrible, but it could also be inspiring.”

A nostalgic longing for the idyllic naiveté that possesses the world of children meets the lament of a divided Korea and a hope for its unification in the 2011 painting A Letter I Cannot Send (2011), an image of one of the artist’s daughters holds a letter to her grandmother, a woman she is unable to contact from across the DMZ.

“[Painting children] reminds me of when I was living in North Korea, as well as when I look at my children,” Sun Mu says. “I’m waiting for my children to grow up to tell them that I’m a defector,” he admits. “I don’t want them to emotionally hurt about the political situation that is happening in the world.”

This article originally appeared on GARAGE.

VIA VICE