North Korean Defector Artist Sun Mu’s Lost Utopias

The former propaganda artist for the DPRK regime now lives in South Korea, after swimming to freedom in the 1990s.

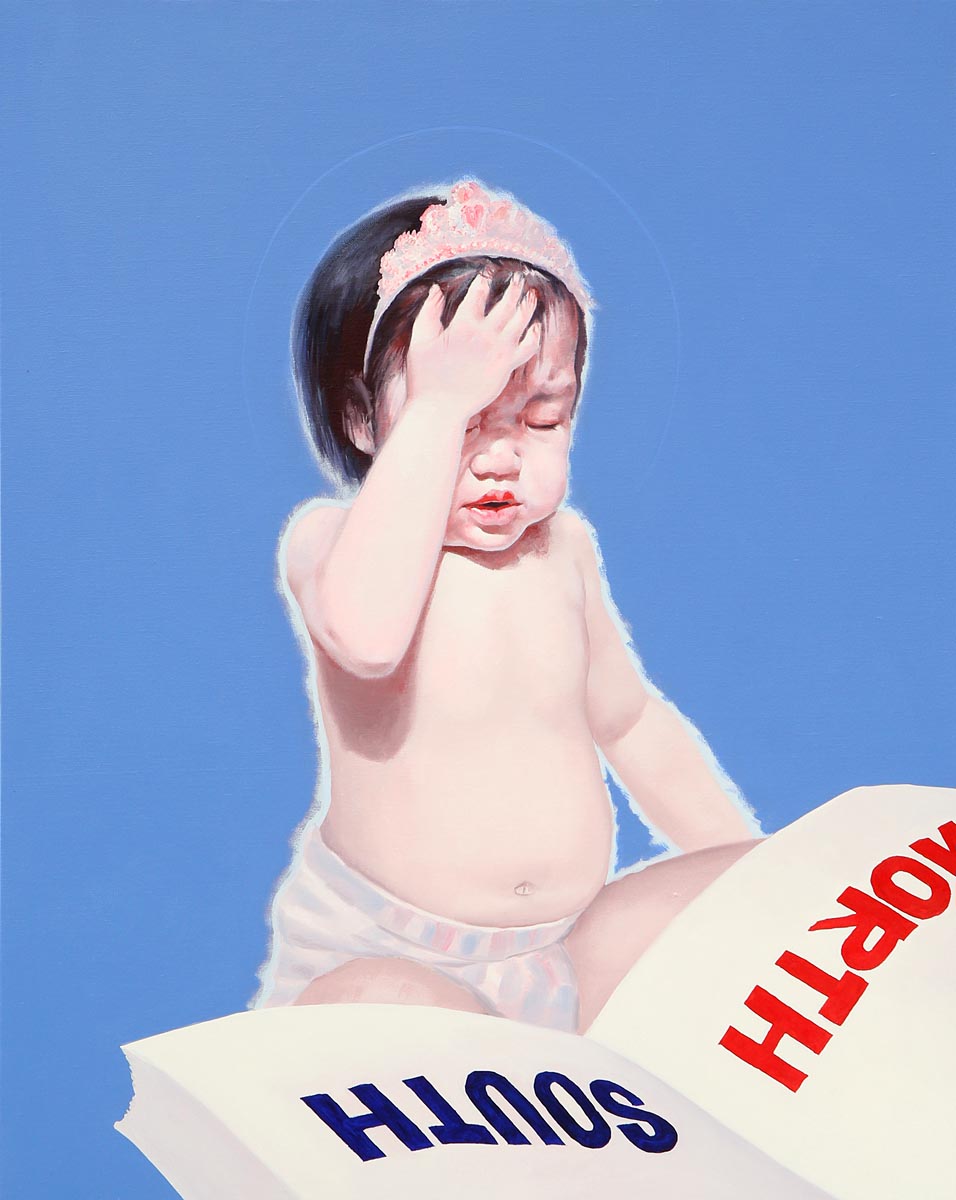

North Korean defector artist Sun Mu’s debut U.S. museum exhibition fixes its axis on lost utopias in halcyon landscapes of childhood and Korean unification. In the 2012 oil painting We Together, on view at Culver City’s Wende Museum, children from the two Koreas run gleefully through a meadow dotted with purple stalks of grass. Another composition shows a boy and girl dressed in as cosmonauts, joined together in a hula hoop.

“If you look at it, this kid is from South Korea, this one is from North Korea,” he tells me. “These children are supposed to have fun together, but they can’t because the country is divided.”

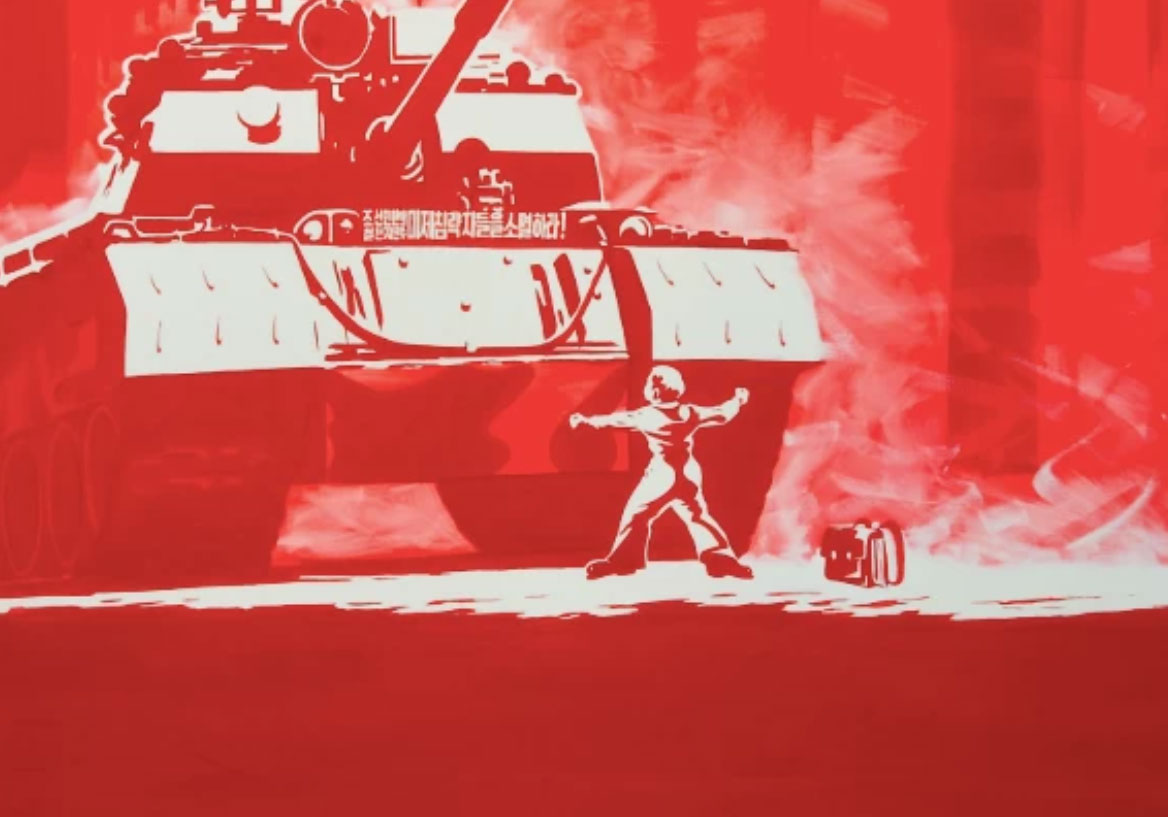

A banner of text cuts through the bottom of the image as in compositions of DPRK propaganda posters and translates to “We want peace,” also the title of the painting. North Korean propaganda posters share the theme of unification, but speak in the triumphalist language of nationalism, while Sun Mu’s compositions are apolitical and focused on the personal realm. A DPRK poster that similarly features a hula hoop functions as political call to action (in this case, “running toward a strong unified country.”)

A bit of Stalinist kitsch: by taking up characteristic tropes of the poster tradition of his homeland, Sun Mu incidentally borrows outfits from the Russians, the cosmonauts’ uniforms an accidental-seeming visual referent to Soviet visions of early space exploration.

The buoyant and sentimental compositions of unification as experienced by children are detailed with care and painted in expressive, saccharine, tones—in stark contrast with the bright bands of red and black the artist uses to capture the intensity of DPRK children and North Korean culture of conformity.

The fascistic salute of uniformed pioneer children in Scenery (2010) is perhaps the most unsettling of these images. Initially, its subjects appear identical or even a single figure reproduced across a canvas. However, as you linger on the figures, tiny variations in their expressions, the shapes of their ties and open mouths become just discernible enough to conjure the eerie specter of a choreographer.

“When I was in North Korea, I was happy as it was,” Sun Mu says of his time as a propaganda artist for the regime. “But now that I'm outside of North Korea, I realize that I actually used these children I was drawing back then as propaganda.”

“I want to keep drawing children, but promoting my own propaganda,” he adds. The artist defines his work as an expression of freedom, and insists that its interpretation is left open to the viewer, a rejection of the DPRK art institution’s central tenet of art being evaluated in terms of its ability to capture objective beauty and transmit an ideological message.

“He is deeply convinced that his artwork has a purpose,” says North Korean art scholar Koen de Ceuster. “Art should not be frivolous, nor simply aesthetic; art has something to say, to add. But what it has to say is for the viewer to pick up.”

The ambiguity of much of the work and its contentious subject matter have garnered controversy both for being too critical of the DPRK and for being insufficiently critical, as the Washington Post points out. The paintings featured in the Wende show were retrieved from China, where they were seized by authorities, a scene depicted in the closing minutes of the 2015 Netflix documentary “I Am Sun Mu.”

This has also been the case in South Korea, where the artist relocated after his defection during the famines of the 1990s by swimming across the Tumen river to China.

“Before I came to South Korea, I thought that it was a country that has no ties to ideology, a country that is really free,” he says. “But when I gave my first exhibition on North Korea I almost got arrested by the police, and so that's when I realized that we didn't know each other. I just had this idea of South Korea that was free of ideology.”

Part of what makes Sun Mu’s art engaging is that it is not dogmatic—in particular, it is not a monolithic criticism of the DPRK. The aesthetic marks of the repressive state also force us to confront the uncomfortable allure of the totalitarian seduction.

“His work is often not crudely anti-North Korea, but rather much more nuanced and multi-layered, where he plays with the appeal of the sugar candy primal colors and the upbeat emotions,” says de Ceuster. “But on closer scrutiny, something is amiss and under the apparent 'happy shiny people' something deeply uncomfortable lingers.”

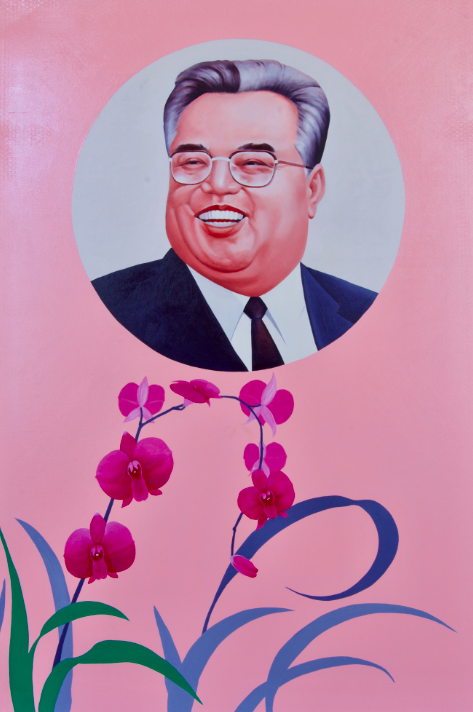

Sun Mu’s work has been widely compared to pop art, and his paintings often satirize the personality cult of the Kim family by placing them in close contact with iconography of consumerism.

“In the United States, they have their own propaganda, just like South Korea has their own propaganda,” he tells me, later noting Trump’s use of defector Ji Seong-Ho as a political prop in his January 2018 State of the Union address. “I want to believe that Trump wants to bring peace in Korean Peninsula,” he says with no intonation of snark. “However, I mostly thought he was using propaganda through [sic] him.”

As Kim Jong-Il once proclaimed, “abstractness in art is death,” the North Korean state is deeply vested in cultivating artists and training them in the tradition of socialist realism and techniques that capture a vision of objective beauty as construed by the ultra nationalist regime and promote its philosophy of Juche (self determination). The more familiar examples of art produced by the regime, its cinema and Arirang Games performance, follow this model.

Wende chief curator curator Joes Segal, too, draws comparisons with the USSR.

“If you look at the role of art in the Western world and under communism, art in the Soviet Union was never meant as decoration,” says Segal. “Is a kind of impulse to make you a better human being, and that could be very horrible, but it could also be inspiring.”

A nostalgic longing for the idyllic naiveté that possesses the world of children meets the lament of a divided Korea and a hope for its unification in the 2011 painting A Letter I Cannot Send (2011), an image of one of the artist’s daughters holds a letter to her grandmother, a woman she is unable to contact from across the DMZ.

“[Painting children] reminds me of when I was living in North Korea, as well as when I look at my children,” Sun Mu says. “I'm waiting for my children to grow up to tell them that I'm a defector,” he admits. “I don't want them to emotionally hurt about the political situation that is happening in the world.”

This article originally appeared on GARAGE.

VIA VICE

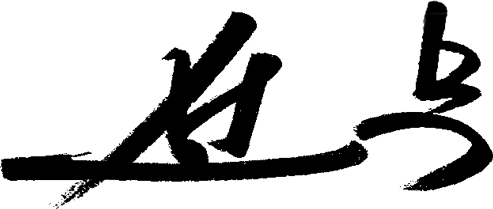

반갑습니다. nice to meet you. 展

매향리 스튜디오는 1968년 미군과 마을주민이 함께 건립한 매향교회 구 예배당을 재생시킨 시설로, 한국 현대사의 상처와 지역의 역사를 예술적으로 해석하는 현대미술 전시를 진행하고 있습니다. 올해는 두번째 전시로 1998년 두만강을 건너 중국, 라오스, 태국 등을 떠돌다 2002년 대한민국에 정착한 선무 개인전을 기획하였습니다. 선무(線無)는 휴전선이 없어지기를 바라는 작가의 예명입니다.

반갑습니다. 문재인 대통령과 김정은 국무위원장 도널드 트럼프 미국 대통령이 매향리 스튜디오에서 만났습니다. 북한에 두고 온 가족을 위해 미디어에 자신의 얼굴을 노출시키지 않는 작가는 이 전시에 대한민국 문재인 대통령, 작가의 고향 조선민주주의인민공화국 김정은 국무위원장, 도널드 트럼프 미국 대통령의 프로필 사진을 그린 대형 초상화 3점을 제작하였습니다.

한반도는 전쟁과 분쟁으로 인해 힘없는 사람이 겪어야 했던 암울한 역사와 분단과 대결의 시대를 끝내려는 전환의 역사가 펼쳐지며 남북정상회담과 판문점 선언, 북미 정상회담이 이어지고 있습니다. 탈북 화가의 붓으로 그려진 3인의 초상에는 인간의 내면, 가치관, 철학, 신념, 냉정함과 치밀함이 드러나는 국가간의 관계와 더불어, 매향리 주민들이 겪어야 했던 암울한 현대사의 상처와 평화의 염원, 그리고 작가의 가족에 대한 애정과 그리움이 담겨있습니다. ● 전시를 시작하는 12월 20일 오후 2시에는 오프닝 특별공연으로 포크록 싱어송라이터 강산에의 무대가 펼쳐집니다. ■ 매향리 스튜디오

his year, the second exhibition of the studio has been planned for the artistic works of Sun Mu, a North Korean defector, who finally settled down in the Republic of Korea in 2002 via China, Laos and Thailand after crossing the Tumen River on the borderline between North Korea and China in 1998. He majored in western painting at school of fine art and graduate school of fine art, Hongik University. ● The artist refrains from exposing his face to media for the safety of his family living in North Korea, and wants to be called 'Sun Mu', the stage name, longing for the demolish of the Military Demarcation Line on the Korean Peninsula. ● The artist painted three large portraits with the profile photos of President Moon Jae-in, Chairman of the State Affairs Commission of the DPRK Kim Jong-un, and President Donald Trump. And they finally got together at the Maehyangri Studio. ● The Korean Peninsula is facing a historic turning point with the inter-Korea summit talks and the Panmunjeom Declaration followed by the DPRK-US summit, which are conducive to the end of gloomy history and the era of division and confrontation ensued from the war and conflicts in the Korean Peninsula. The portraits of the three leaders, along with their relations between nations based on their cool-headedness and meticulous nature, reveal their inner thoughts, values, philosophy, and beliefs while they reflect the grim scars of the modern history and the wish for peace as well as the affection and longing for the artist's family. ● At 2 pm on December 20, Kang Sane, a famous rocker and singer song-writer, will give his special performance for the opening of the exhibition. He participated in Pyongyang Concert held during President Moon's Pyongyang visit. ■ Maehyangri Studio

두개의 심장 / Two Hearts / Zwei Herzen展

두개의 심장 ● 2002년, 대한민국이 붉은악마의 물결로 일렁이던 해에 선무는 남한에 왔다. 마치 북쪽의 집단체조를 연상시키며 모두가 하나 되어 외치는 '대한민국'은 선무에게는 너무나 익숙한 일상이었기에 북이나 남이나 별 다를 것 없는 사람 사는 세상으로 비춰지기도 했다. 다만 감시하는 사람도 없고, 누가 시키지도 않았으며, 더구나 연습된 상황도 아니었다는 것을 깨닫게 되면서 북과 남 사이에 높게 쌓인 벽들이 선무의 눈에 들어왔다. 아직 대한민국에 초짜인 선무에게 한갓 볼 차기 게임을 놓고 밤새도록 광란하며 거리를 무리지어 싸돌아다니는 무정부 상태가 결코 옳을 수는 없었다. ● 선무가 북쪽을 벗어난 것은 세계가 세기말 몸살을 앓고 있던 1998년이었다. 남한 사회에서는 아직도 휴거(携擧)를 두려워하는 이들도 있었으며, 외환위기로 인해 새천년의 기대감이 상쇄되던 때였다. 남한에 들어오기까지 3년 반 남짓한 시간들은 선무에게는 암흑기였다. 아시아의 덜 성숙된 몇몇 국가들을 표류하며 20세기 야만의 질곡을 벗어나지 못한 무지막지하게 팽창된 제도들에 의해 봉인된 삶의 연속이었기 때문이다. 마치 거울로 된 유리방에 갇혀 무수히 반복되어 반사된 헤아릴 수 없는 자신들에 의해 정작 나 자신의 실체가 실종되어버린 기억조차 떠올리기 싫은 유치된 자아의 시간이었던 것이다. 오직 그에겐 동물처럼 생존만이 중요했을 뿐이다. 아직도 이로부터 홀연히 벗어난 것은 아니지만 그나마 그의 인생에서 유리방을 빠져나와 거울을 똑바로 바라볼 수 있는 용기와 여유가 생긴 것만은 사실이다. ● 그렇다고 근 10여년간의 남한생활이 30여년의 북쪽생활을 지울 수 없다. 더구나 개인의 삶을 주체적으로 영유하며 보냈던 시간이 짧았던 선무에게 있어서는 아직도 전체주의의 환영과 지배와 피지배의 틈을 교묘히 노리는 욕심들의 악취를 떨쳐버리기 버겁다. 그래도 남한에서의 시간은 여러 사람들과의 상봉과 이별을 만들어주었다. 그 사이 대학과 대학원을 졸업했으며 수차례의 개인전과 각종 국제전에 초대되어 뜻하지 않은 외국여행의 기회도 가질 수 있었다. 이제는 몰래 숨어들거나 빠져나오는 것이 아니라 당당하게 예술가의 자격으로 국경을 넘나드는 나름 지구인이 된 셈이다.

소리가 보이고, 색깔이 들린다. ● 알록달록하고 다소 시끄럽게도 느껴지지만 선무 작품을 보면서 드는 생각이다. 뭔가 배경음악 내지는 많은 사람들의 구령 또는 구호소리가 요란할 것 같다. 그리고 코카콜라 광고판도 아닌데 생색들이 화폭에서 부유한다. 한마디로 뭔가 격양된 분위기가 있다. 더구나 북쪽의 선명한 글씨체들이 뒤섞인 화폭에서는 지난 20세기 거대사상의 유령들이 전체주의에 복무할 것을 재촉한다. 21세기 들어와 그 유령들이 두려운 존재는 아니지만 아직도 엄연히 발견되는 일상에서의 벽들은 새삼 인간들이 만들어낸 이념의 금자탑을 반성하게 만든다. 어찌되었건 선무 작품에 등장하는 인민들은 조국이라는 유토피아에 귀의하여 갓 세상에 눈을 뜬 순진하고 호기심 많은 어린아이의 표정으로 우리를 응시하고 있다. 그리고 하늘에 태양이 하나인 것을 당연하게 받아들이며 그 따스함을 즐기고 있다. 해바라기 입장에선 어둠 속에 반짝이는 달과 별들을 본 적이 없는 까닭이다. ● 한편 '식민지 조국의 품안에 태어나 세상에 부럼 없이 사는 방법'을 찾으려 했던 유토피아의 지도자는 선무의 화폭에서 너무나 의연하게 그려진다. 오히려 역설적으로 그 당찬 꿈이 아직도 선무에게 남아 있는 것처럼 말이다. 분명 앤디 워홀의 마오나 중국 당대 예술인들이 그려낸 마오의 초상과는 전혀 다른 맥락이다. 최근에는 그 지도자의 얼굴에 종교적 숭배의 이미지가 합성되었다. 이념적 우상화와 종교적 아이콘 그리고 다국적 자본주의의 심볼들에 섞여버린 지도자의 초상. 굳이 그것을 특정인물의 초상화라 칭할 필요는 없을 것 같다. 오히려 이상한 나라의 앨리스가 빠져들어 갔던 거울처럼 엄청난 흡입력을 지닌 세상에 반추된 생경한 풍경화로 보여지기도 한다.

문제는 미래다. ● 과거 변혁에 복무했던 사회주의 창작방법론의 대부분이 그러했듯이 북쪽 영도예술론의 핵심도 사람이다. 물론 북쪽에서는 그 사람이 어떤 사람이냐가 더 중요하겠지만 반쪽 국가를 넘어온 예술가 선무의 입장에서는 쉽게 지울 수 있는 기억들이 아니다. 더구나 머리가 아니라 몸에 스며든 창작태도는 불혹을 넘어선 나이에 바꾸기란 여간 어려운 일이 아니다. 물론 북쪽에서 미술을 전공하기는 했지만 선무는 인민예술가도 창작소의 일원도 아니었다. 하지만 시각문화라는 것은 보이는 것이라 창작이 결과 되기까지 상당부분을 환경의 영향을 받는다. 더구나 내용담지체적 형식인 조형작품에 있어서 형식은 당대의 지적 기술적 여건과 시각적 충격의 경험치를 벗어나기 힘들다. 그나마 남한 시각문화의 축적도가 이제는 결코 얇지 않기에 선무라는 작가의 자유로운 활동이 허용된다는 것은 정말 다행이다. 그리고 노파심이지만 선무의 작업을 단순하게 '반공포스터'로 읽으려 하거나 '삐라'처럼 불온하게 위치시키려는 아둔한 생각들은 없길 바란다. ● 선무 작품이 지칭하는 장소는 과거가 아니라 미래이다. 우리가 선무 작품을 보면서 자꾸 과거 냉전의 시대로 회귀하려는 느낌을 지울 수 없는 것은 북쪽 예술 및 문화에 대한 정보가 너무 미천한 탓이다. 그리고 지난 세기 이성과 체제에 대한 과신이 만들어낸 야만적 지배구조의 잔해들 때문일 것이다. ● 하늘에 밝은 태양이 지고 나면 아련한 달과 무수히 많은 별들이 모습을 드러낸다. 그리고 또다시 태양은 뜨겠지만 어제의 태양은 오늘의 태양이 아니다. 물론 그것을 바라보는 나 또한 어제의 내가 아니듯이... ■ 최금수 (2010년 9월, 남한에서)

Zwei Herzen ● Im Jahre 2002, als Süd Korea in Euphorie über die Teilnahme an der Fußballweltmeisterschaft war, mitten in der wogenden Welle des "Roten Teufels", wie die begeisterten Fußballfans von Südkorea genannt wurden, ging Sunmu, aus Nordkorea in das südkoreanische Exil. Die Fußballhytserie erinnerte ihn an die Gymnastikübungen der Kommunistischen Sportgruppen. Das im Einklang geschriene "Dae-han-min-kook (Los Korea!)" der "Roten Teufel" klang ihm vertraut und für einen kurzen Moment erschien es ihm, als ob Nord und Süd gar nicht so verschieden waren. Doch als Sunmu bemerkte, dass es keine Überwachung gab, keine Befehle und nichts vorher einstudiert wurde, wurde ihm der große Unterschied zwischen Nord und Süd bewusst. Aus Nordkorea stammend und als Neuling im Süden, konnte Sunmu die übertriebene Ekstase und das "anarchistische" Verhalten nicht verstehen, dass die singenden und auf den Straßen herumlaufenden "Rote Teufel" Fans, nur wegen eines trivialen Sportereignisses umhertrieb. ● Sunmu flüchtete im Jahr 1998 aus Nord Korea, als die ganze Welt unter den Unruhen des fin-de-siecle litt. Manch ein Koreaner fürchtete die Apokalypse. Jegliche hoffnungsvolle Stimmung wurde zudem unterdrückt, als Südkorea vom Internationalen Währungsfonds (IMF) zu Sparmaßnamen für das kommende neue Jahrtausend aufgerufen wurde. Die drei Jahre unmittelbar bevor Sunmu nach Südkorea gelangte, waren eine dunkle und schreckliche Zeit für ihn. Dies waren die Tage, als Sunmu durch verschiedene Länder reiste und ihm sein Leben von monströsen und repressiven Regierungsverwaltungen schwer gemacht wurde. Das war eine Zeit in der er sich verloren fühlte, als ob er in einen Raum voller Spiegel gesperrt worden wäre, die die Bilder ins Unendliche reflektierten und verzerrten, in denen er seine Identität inmitten des Chaos verlor. Es war beinahe zu schmerzhaft, daran zurück zu denken. Der animalische Instinkt des Überlebens war das einzige, das Sunmu aufrechterhielt. Obwohl seine schreckliche Vergangenheit nicht völlig vergessen war, hat er nun das Gefühl dem Spiegelraum entkommen zu sein und sein unverzerrtes Bild zu sehen. ● Auch die zehn Jahre die er in Südkorea verbracht hat, können die traumatischen Erfahrungen von dreißig Jahren in Nordkorea nicht vergessen machen. Für Sunmu war die Freude an einem Leben in einer freien und demokratischen Gesellschaft zu kurz, der Gestank und das Schreckgespenst des Totalitarismus verfolgen ihn immer noch hartnäckig. Der Neuanfang in Südkorea hat ihm Treffen mit neuen Leuten und neuen Möglichkeiten verschafft. Er konnte seinen Bachelor und Master abschließen; er nahm an zahlreichen Einzelausstellungen teil und wurde zu internationalen Kunstausstellungen eingeladen, wodurch er die Möglichkeit erhielt ins Ausland zu reisen. Sunmu war nicht mehr gezwungen sich heimlich seinen Weg in Länder hinein und heraus zu schleusen, er konnte nun als stolzer Weltenbürger, die Grenzen als internationaler Künstler überschreiten.

"The Sound May be Seen, The Color May be Heard" (Der Ton ist zu sehen, die Farbe zu hören)● "Das sind meine Gedanken, wenn ich Sunmus Arbeit sehe, welche mir eher bunt und laut vorkommt. Ich habe das Gefühl Hintergrundmusik zu hören oder den Gesang von Menschen. Die hellen, rohen Farben scheinen mit denen aus Coca-Cola-Anzeigen zu konkurrieren. Um es in andere Worte zu fassen, die Stimmung in seinen Werken ist erhaben. "Ausserdem bringt die mit nordkoreanischen Propagandaslogans vermischte Bildsprache und die Blockschrift kontrastreicher Farben die Erinnerung an ein totalitäres Regime als Phantom der großen Ideologie zurück. Im 21. Jahrhundert, sind diese Phantome nicht länger Gegenstand unserer Angst, aber deren Überbleibsel, die wir immer noch in unseren Leben spüren, lassen uns die monumentale Ideologie bereuen. Trotz alledem, erscheinen uns die Gesichter der Bevölkerung in Sunmus Arbeit wie Sonnenblumen, die uns mit unschuldigen und neugierigen kindlichen Blick anstarren, die sich nach einer utopischen Heimat sehnen. Diese Sonnenblumen haben nie andere Monde oder Sterne im Himmel gesehen. Sie genießen die Sonne blind, im Glauben, dass nur eine Sonne im Universum existiert. ● Der ehrgeizige nordkoreanische Führer, wird von Sunmu ironischer Weise immer noch lebensnah und nach Utopia suchend dargestellt. Anders als in den Mao Bildern Andy Warhols oder anderer zeitgenössischer chinesischer Künstler. Erst vor kurzem begann Sunmu religiöse Kultbilder in das Gesicht des Anführers zu malen und zu integrieren, die mit ideologischen und internationalen kapitalistischen Symbolen vermischt waren. Es ist nicht das Portrait einer spezifischen Person; eher erscheint es eine fremde Landschaft zu sein, in der alles aufgesogen wurde, wie der Spiegel der Alice im Wunderland verschluckt hat.

Was zählt ist die Zukunft ●Wie der Großteil der vergangenen sozialistischen, künstlerischen Vorgehensweise, die für Revolution und sozialen Wandel gedacht war, liegt der Schwerpunkt der nordkoreanischen Lehr- und Propagandakunst auf dem Menschen. Selbstverständlich, wurde im Norden die Kunst instrumentalisiert um Ideologie zu propagieren und die Denkweise der Menschen so zu verändern, dass die Revolution aufrecht erhalten bleibt. Obwohl Sunmu die Grenze überschritten hat, können diese Erinnerungen nicht ohne weiteres ausradiert werden. Es ist nicht leicht, den künstlerischen Stil zu verändern, der Sunmu bis zu seinem 40. Lebensjahr geprägt hat. Obwohl er seinen Abschluss in Malerei gemacht hat, war er kein etablierter, preisgekrönter Künstler oder Mitglied von "Mansudae", dem wichtigsten Kunststudio in Nord Korea. In der bildenden Kunst wird die Form wesentlich durch die Bedingungen von Wissen, Technologie und zeitgenössischer, visueller Bilder beeinflusst. Es ist ermutigend zu sehen, dass die visuelle Kultur in Südkorea divers und gereift ist um Sunmus Arbeit und seine künstlerischen Tätigkeiten anzunehmen. Doch man sollte beachten, Sunmus Arbeiten nicht einfach als "antikommunistisches, politisches Plakat" oder "Propagandaflugblatt" zu lesen. Sunmus Arbeiten adressieren nicht die Vergangenheit, sondern die Zukunft. Aufgrund des Mangels an Wissen über die nordkoreanische Kunst und Kultur fallen wir beim Betrachten der Arbeit von Sunmu und ständig in die Erinnerung an die Zeit des Kalten Krieges zurück. Dies sind nur die Überreste in unserem Denken, zurückgelassen von einem barbarischen und dominanten System, das durch ein Übermaß an menschlicher Logik und Rationalität geschaffen wurde. ● Nachdem die Sonne untergegangen ist, erscheint ein vager Mond und tausende von Sternen. Die Sonne wird wieder aufgehen, aber die Sonne von morgen ist nicht die gleiche wie heute. Natürlich werde ich, wenn ich auf die aufgehende Sonne schaue, nicht dieselbe Person sein wie gestern... ■ Choi Geumsoo (September 2010, in South Korea / Übersetzung vom Koreanischen ins Englische: Choi Sooran; Übersetzung vom Englischen ins Deutsche: Hannah Cooke)

Two Hearts ●In 2002, when South Korea was ecstatic over its participation in World Cup Soccer, in the midst of the swaying wave by "Red Devil," the name given to the avid World Cup Soccer fans in South Korea, Sunmu, an exile from North Korea arrived in South Korea. The soccer hysteria reminded him of the Communist group gym physical activities, The Red Devil's united crying of "Dae-han-min-kook (Go Korea!)" sounded familiar to him, and for a moment, he felt North and South were not very different. But, when Sunmu realized there was no surveillance, no orders, and nothing was previously choreographed, the huge gap between North and South became real to Sunmu. As a newcomer to the South Korea from North Korea, Sunmu couldn't understand nor appreciate the over wrought frenzy and "anarchistic" behaviors of singing and running around on the streets by the Red Devil fans over a trivial sport's game. ● Sunmu escaped from North Korea in 1998 when the whole world was suffering fin-de-siecle unrest. There were Koreans who feared the apocalypse. Further depressing any hopeful mood, South Korea was called to financial austerity by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for the coming new millennium. The three years immediately before Sunmu actually reached South Korea was a dark and horrific period for Sunmu. Those were days when Sunmu wandered through several different countries where monstrous and repressive governmental administrations made his life depressing. It was a time when he felt lost, as if he was locked in a room of mirrors that reflected and distorted images endlessly, disorienting, and losing one's identity amid the chaos. It was almost too painful to recall. The animal survival instinct was the only thing that sustained Sunmu. Although his frightful past is not totally forgotten, Sunmu now, at least feels that he escaped the mirror room and can see his undistorted image. ● Ten years of living in South Korea cannot overshadow thirty years of his traumatic experience in the North. For Sunmu, the joy of living in a free and democratic society has been too short, the stench and spector of totalitarianism doggedly haunts him still. But a new beginning in South Korea has brought him meeting with new people along with new possibilities. He has earned his Bachelors and Masters of Art degrees; participated in several solo art exhibitions, and gained the chance to travel to foreign countries from invitations to international art exhibitions. Sunmu no longer is forced to surreptitiously sneak his way in and out of countries, but has become a proud world citizen who can cross international borders as an artist.

The Sound May be Seen, The Color May be Heard ● These are my thoughts when I see Sunmu's work which appears to me rather colorful and loud. I feel that I can hear background music, or people chanting. The bright raw colors appear competing with those in Coca Cola ads. In other words, there is an exalted mood about his work. Furthermore, the imagery mingled with North Korean propaganda slogans along with the block lettering of contrasted color brings back the memory of a totalitarian regime as a phantom of grand ideology. In the 21st century, these phantoms are no longer our object of fear, but their trace remnants still felt in our daily lives make us regret such monumental ideologies. Nevertheless, the populace in Sunmu's work appears as sunflowers gazing at us with innocent and curious childlike faces longing for a Utopian homeland. Those sunflowers have never seen other moons or stars in the sky. They enjoy the sun blindly believing that there is only one sun in the universe. ● The ambitious North Korean leader seeking Utopia is vividly depicted, as if ironically, that ambition still remains in Sunmu's mind. It is different from the Mao's images by Andy Warhol or by other contemporary Chinese artists. Recently, Sunmu started to depict and incorporate within the leader's face, religious cult images mixed with Ideological and international capitalist symbols. It is not a specific person's portrait; rather, it seems to be an unfamiliar landscape in which everything is absorbed, like the mirror that swallowed Alice in Alice-in-Wonderland.

What Matters is the Future ●Like most of the socialist artistic methodology in the past which was intended for revolution and social change, the focus of North Korean didactic, and propaganda art is man. Of course, in the North, art is utilized to propagate ideology and to change people's minds to sustain the revolution. Although Sunmu crossed the border, these memories cannot be readily erased. It is not easy to change the art making style that was internalized within Sunmu up to his age of 40. Although he majored in painting, he was not an established awarded artist nor a member of Mansudae, the major art studio in North Korea. In visual arts, form is significantly affected by the condition of knowledge, technology and contemporary visual imagery. It is encouraging to see visual culture in South Korea has been diversified and matured enough to embrace Sunmu's work and his artistic activities. Just for caution's sake, please don't read Sunmu's work simply as an "anti-communist political poster" or a "propaganda leaflet." ● What Sunmu's work addresses is not the past but the future. It is due to the lack of our knowledge about North Korean art and culture that we constantly fall back to the memory of the Cold War period when we view Sunmu's work. These are just remnants in our minds left behind from the barbaric dominant system created by an overconfidence in human logic and rationality. ● After the Sun sets, there appears a vague moon and myriads of stars. The Sun will rise again, but tomorrow's Sun is not the same as the one today. Of course, I, looking at the rising Sun, won't be the same person as yesterday... ■ Choi Geumsoo (September 2010, in South Korea / Translation: Choi Sooran)

Inside Sun Mu's Studio: From North Korean Propaganda to Satirical Art

Korean artist Sun Mu works from a modest studio on the outskirts of Seoul. Dozens of baseballs hang on strings from the ceiling — is he a fan? ‘No,’ he says, seriously. The balls symbolise his dream for Korean unity; two equal halves curl around each other to create a smooth, round globe.

‘Political unification, that’s not proper unification… when we meet, drink and work together, that’s when reunification takes place,’ Sun Mu says. After all, ‘how are we supposed to talk about reunification when we don’t even know each other?’

Early life in North Korea

Sun Mu was born in North Korea, where his artistic talent was recognised at a young age. As a child, he was picked to perform at Pyongyang Palace as part of the country’s annual New Year’s celebrations, where children sing, write, and paint for the North Korean leader. ‘I had seen those things, so I wanted to do it and please Kim Il Sung,’ he recalled. This was the start of his career, and led to his training as an artist there, where he painted posters in the regime’s socialist realist style.

Sun Mu was unusual amongst North Korean defectors, as he didn’t initially want to leave the country. Although everyday life required strict adherence to the government’s ideology, he believed in it. ‘If the system worked well, things would be great. There would be no taxes, no tuition fees, no unemployment,’ he said. Before leaving the country, Sun Mu was ‘ready to die’ for North Korea.

Stateless in China

But in the late 1990s, he was forced to defect. North Korea suffered a mass famine where, by some estimates, up to three million died from starvation. ‘I was sure I would die there’, Sun Mu said. He crossed the border into China. But being stateless proved difficult and the artist became involved with dangerous criminal gangs.

‘Living without a proper identity isn’t a good experience,’ Sun Mu said. ‘But in order to retain my identity, I would have had to go back to North Korea.’ Despite the dangers, he decided to move to Laos and then Thailand, escaping his gang’s house in the dead of night. Had he been caught, he would have been killed.

Growing up in North Korea, he was told that South Korea was highly Americanised, decadent and capitalistic. He was also told that the country was made up of tight-knit educational, regional and blood relationships – that it would be difficult for him to find acceptance. The decision to move to Seoul wasn’t an easy one, but Sun Mu was also aware that South Korea could give him the citizenship he needed.

Finally free?

After arriving in Seoul in 2002, Sun Mu continued to paint. He went back to college at the renowned Hongik University and majored in Arts. As he developed as a painter, he grew increasingly critical of North Korea. He subverted the propaganda style in which he was trained to create satirical works that mocked the regime’s ideology. In one painting, a podgy Kim Jong Un smiles as images of war are reflected in his gleaming sunglasses. In another, a sickly Kim Jong Il is offered Coca-Cola (a symbol of American capitalism) as medicine by a healthy young girl.

Given the controversial nature of his artwork, there are aspects of himself which he is unable to share. Sun Mu is not his real name — it’s a pseudonym, adopted to prevent reprisals against his family still living in North Korea. If one family member commits an offence against the state, the regime’s three-generation rule sees whole families punished. For the same reason, the artist does not show his face in public. ‘I show myself through my work,’ he says.

Though the punishment is less severe, the freedom Sun Mu has to express himself through art is still limited in South Korea. Under the country’s National Security Law, praising North Korea is a crime, and Sun Mu’s art has stoked controversy from the very beginning. When he celebrated the opening of his first exhibition, police arrived to investigate a complaint that his work was pro-North Korea. As similar complaints were made about subsequent exhibitions, regional police investigations became a fixture of the artist’s life.

While Sun Mu has built a new life in South Korea, some of his initial fears of living there have been confirmed. ‘I think [South Koreans] care too much about money,’ he reflects. The country’s high-powered, competitive economy and individualistic outlook on life has changed the subject of his art. Rather than painting propaganda for the North Korean regime, ‘I was advertising myself — self propaganda,’ Sun Mu reflected.

‘No Borders’

The complaints made against his work initially came as a surprise, spurring Sun Mu on to one of his biggest dreams. ‘The ideas of ordinary people were still in that Cold War ideology,’ he said. ‘We should move away from that ideology and create a society where we can talk.’ The artist sees communication not just as a means to reconciliation, but as an end in and of itself. Even his assumed name expresses a desire for unity — Sun Mu translates to ‘No Borders’.

Even though both countries have their own problems, Sun Mu’s overarching message is one of optimism. As well as the baseballs, all over his studio are flowers. The stalks are made of barbed wire from the demilitarised zone (DMZ) separating the two nations, to which Sun Mu has added yellow blossoms. The image symbolises renewal and hope for the future. Many of Sun Mu’s works feature children from the North and South playing hand in hand, in a show of the unity he desires. ‘Even though we’re different,’ Sun Mu says, ‘we can live with one another.’

via Culture Trip

Dans l'atelier de Sun Mu

Même la question des rapports avec la Corée du Nord, l'objet du reportage qui me ramène sur place, prend des proportions inenvisageables au siècle dernier. Pour preuve, Benjamin Joinau me propose de l'accompagner, avec Diane Josse, attachée culturelle à l'ambassade de France, dans la banlieue de Séoul, visiter l'atelier du peintre Sun Mu.\

Né au début des années 1970 au Nord, celui-ci devient l'exécutant de fresques à la gloire du régime dans une petite ville. Avant ses 30 ans, il s'enfuit, gagne Séoul, y étudie l'art sans y comprendre goutte, avant un déclic en troisième année : il se servira de la propagande dont il fut saturé pour trouver son mode d'expression.

Dans l'atelier de Sun Mu : tronc scié...

Sun Mu a choisi un pseudonyme qui signifie « sans frontière ». La question de la partition de la péninsule le hante, mais il en joue, l'affronte, la contourne, l'allégorise. La nature devient, sous son pinceau, la métaphore de ce qui fut et reste sectionné. On pense, face à certaines toiles, au passage de l'Évangile de Matthieu : « Si ta main ou ton pied est pour toi une occasion de chute, coupe-les et jette-les loin de toi ; mieux vaut pour toi entrer dans la vie boiteux ou manchot, que d'avoir deux pieds ou deux mains et d'être jeté dans le feu éternel. Et si ton œil est pour toi une occasion de chute, arrache-le et jette-le loin de toi ; mieux vaut pour toi entrer dans la vie, n'ayant qu'un œil, que d'avoir deux yeux et d'être jeté dans le feu de la géhenne. »

À la douleur de la solution de continuité (qui signifie donc discontinuité) coréenne, Sun Mu mêle l'ironie d'un regard sans concession sur les petitesses, aberrations, méprises, tares, ou névroses septentrionales comme méridionales. Sa vie est menacée. Il m'interdit de le photographier mais laisse entière liberté pour fixer ses œuvres – certaines illustreront la série de reportages que Mediapart va mettre en ligne dans la perspective du sommet de Singapour, prévu le 12 juin entre Kim Jong-un et Donald Trump.

Sun Mu est haï par le régime de Pyongyang, qui a tenté de le kidnapper lors d'une exposition à Pékin. Les services secrets chinois ont exfiltré le créateur, mais détruit tous les catalogues de l'exposition, histoire de donner des gages à la Corée du Nord en pétard. Sun Mu n'est pas mieux vu à Séoul. Les galeries rechignent à l'exposer : des citoyens âgés, gavés d'une propagande inculquée du temps des régimes autoritaires de la Corée du Sud militariste, quand ils tombent sur les toiles de Sun Mu, filent dénoncer au commissariat du coin l'artiste pop art incompris !

En ce moment, Sun Mu fait de surcroît les frais du rapprochement entre Séoul et Pyongyang : aucun musée, pas la moindre biennale ne l'invite désormais dans la Corée méridionale, qui ne veut surtout pas fâcher son voisin septentrional si sourcilleux sur le culte de soi-même, au point de considérer l'artiste transfuge tel un hérétique et pas seulement un traître...

Sun Mu m'apparaît donc comme le symbole le plus éclatant des bouleversements et des invariants, en une Corée du Sud devenue kaléidoscopique, diverse, capable de toujours s'enfoncer dans le conformisme néo-confucéen comme de s'en sortir en s'ébrouant jusqu'à proposer, en une modernité bien effrénée, des regards de biais décapants. Le tout dans une énergie où se mêlent douceur et voracité. C'est un pays si attachant que je n'ai cessé, dix jours durant, de me demander pourquoi je m'en étais détaché.

via Mediapart

Sun Mu’s satirical art: The Korean detente through the eyes of a defector

As the Winter Olympic Games take place in South Korea, FRANCE 24 talks to a North Korea-born artist about his satirical work.

The opening ceremony at this month's Winter Olympics Games was a dazzling spectacle. But what stole the show was the image of athletes from North and South Korea walking side-by-side behind a unified flag – embodying the hopes of a peninsula divided by ideology and mistrust.

The apparent detente caught the world by surprise. In 2017 the threat of nuclear missile attack by Pyongyang reached an all-time high.

South Korea’s President Moon Jae-in was later invited to the country’s neighbouring North – sparking optimism that a rapprochement could avert a possible devastating conflict.

But this is a trip that Sun Mu - a pseudonym that translates into “No Boundaries” – is not likely to take any time soon. The North Korea-born artist is among those who have made their way to safety in the South. According to one NGO, an estimated 300,000 North Koreans have defected since the end of the Korean War in 1953.

Sun Mu tells FRANCE 24 nothing has changed since his escape in 1999: "If the situation had improved, North Korea would have opened up. And people like me would be able to go back and forth."

A perilous journey

Growing up under the iron fist of Kim Il-Sung, the founder of North Korea, defecting was not Sun Mu’s original plan.

“I thought North Korea was a good country. I was one of those who were willing to die for their leader. But in the end, when you're hungry... you need to eat.”

In the late 90s, during a mass famine that by some estimates killed three million people, Sun Mu made his escape by crossing the Tumen river into China, before heading south.

“When I arrived in China, I realised how difficult life was going to be without a legal identity. I said to myself, the south is my land too. I'd also heard that people like me were automatically granted citizenship. So I bought a map, and ended up taking a bus to Laos, before traveling to Thailand. From there, I took a flight to South Korea. That was in 2002. I didn't have a real plan, but I thought to myself, I'd rather die trying than live without an identity.”

Politics on a canvas

Trained as a propaganda artist in his native North, Sun Mu felt that there was little else he wanted to do. Free from the constraints of the dictatorship, he started painting again, and eventually discovered his own style. He began producing satirical works: blending images of North Korean communism with pop art, sometimes even drawing inspiration from the colourful world of Disney.

“My work, what I call ‘my propaganda’, does contain criticism of the regime. But it also contains a lot of my thoughts, my hopes for the future in images."

Over the years, Sun Mu - now in his mid 40s - has been taking his art across the globe, from South Korea to China to the United States and Germany. But his satire is largely misunderstood in cities like Seoul, where painting pictures of the ruling dynasty is considered a crime under national security laws.

Upside-down propaganda

In Sun Mu’s "Some Take Medicine", a rosy-cheeked young girl offers a Coca-Cola, a symbol of capitalist America, to the sickly former leader of the North, Kim Jong Il – who died in 2011. For the artist, the message of this piece is that the isolated country needs “to open its doors before it can begin to live".

Perhaps one of Sun Mu’s most recognised paintings is a close-up of Kim Jong Il wearing his trademark Ray Ban sunglasses. He calls it "Control". At first glance, this could be any other portrait of the country’s leader that adorns thousands of walls in the North – in homes, in offices, at schools. But on closer inspection, the image reflected in his sunglasses carries Sun Mu’s own message, an expression of fear: hungry workers in the field fleeing, as a soldier points his gun at them. This - whilst men and women from various religious faiths stand by and watch.

In another piece, entitled ‘A Song of Joy’, a young uniformed schoolgirl at the centre of the canvas is smiling widely, unaware that those outside are living different lives… that “they are experiencing another kind of happiness,” Sun Mu explains.

Obstacles

During his first show in the southern capital, the police turned up to investigate.

“South Koreans are skeptical of my work. Many of them still have Cold War mentalities," says Sun Mu.

Worse yet, in Beijing his display was shut down and some 70 paintings were seized. Even 800 kilometres away from the watchful eye of the North, Sun Mu’s art was being silenced. Until that point, no North Korean had held a solo exhibition in China without supervision from Pyongyang.

While Sun Mu was preparing to uncover this show in 2014, the process was documented by filmmaker Adam Sjoberg, who had previously worked on conflict zones and natural disasters.

I Am Sun Mu was released in 2015.

“I wanted to understand North Korea beyond the headlines,” Sjoberg tells FRANCE 24.

“That’s why I love people like Sun Mu, who don’t paint in black and white, either figuratively or literally, but rather communicate the complexities of the North while imbuing something dark with a sense of hope and even humour,” he adds.

But even in what was supposed to be a quasi tell-all, the artist “couldn’t reveal everything".

“If I gave away too much information, people in the North could get hurt... I actually had to ask the director to take several scenes out," explains Sun Mu.

Despite becoming a public figure, Sun Mu’s true identity remains a mystery. He never shows his face to the camera, often appearing in silhouette or from the back.

"I've always been cautious because the danger is very real. I'm living here with my new family but I do have to think of my parents and siblings in the North. I can't be completely sure of my own safety here. I am however, definitely better off in South Korea than I would be in China."

Hopes for the future

But Sun Mu still clings to hope, especially at a time when many observers are cynical about a North-South detente: "If both sides have the will, there will be a way.”

But he is critical of excessive foreign interference.

"It's a pity that several heads of state are using this reunion for their own political gains, to please their electorates... I'm just sick and tired of the US, Russia, China and Japan… In fact in one of my artworks I’ve thrown specks of red paint all over them.”

The red paint represents the blood that these "leaders" -- also the name of the painting -- have on their hands.

Sun Mu ends the conversation by comparing his own country’s leadership to that of the US.

“Donald Trump and Kim Jung Un are not so different. I think if they came face to face, they would actually get along. The big question is, will there ever be an opportunity for the two of them to meet?"

via france24

Meet North Korean Defector and Propaganda Artist, Sun Mu

Kim Jong Un and Disney are probably the unlikeliest of pairings, but one North Korean defector is marrying the two in his subversive art. Sun Mu fled North Korea more than 20 years ago, and he’s been using his art for change ever since – images of North Korean communism colliding with western capitalism and pop culture.

via YouTube

[Why] 국경도 얼굴도 없는 탈북화가, 나는 선무다

[박돈규 기자의 2사만루] 국내외서 가장 비싼 탈북화가

北서 배운 프로파간다 미술로 그곳의 '최고 존엄' 조롱

"처음엔 김정일 그리는데 붓이 떨렸어요, 너무 무서워서"

참이슬·대동강맥주 그려놓곤 "통일 폭탄주인데, 맛이 좋습니다"

1998년 10월 두만강 앞에서 한참을 망설였다. 건너야 하나 말아야 하나. 그는 담배밭에 숨어 밤이 오길 기다렸다.

"풀벌레 울음소리가 크게 들렸어요. 얼마나 지났을까. 불안과 공포 속에 강으로 걸어 들어갔습니다. 북한 쪽 수심은 얕아요. 중국으로 가까이 갈수록 툭 떨어졌습니다. 거기서부터는 헤엄을 쳤어요."

'얼굴 없는 화가' 선무(線無·46)는 20년 전으로 돌아간 표정이었다. 등유 난로에 올려놓은 주전자가 김을 내뿜고 있었다. "북한에서 살 땐 심장도 내 것이 아니었다"며 그가 말을 이었다. "가슴팍에 김일성·김정일 초상휘장을 달고 다녔지요. 탈북(脫北)하곤 떼어 버렸어요. 이제 심장은 저를 위해서만 뜁니다."

그는 국내외에서 작품값이 가장 비싼 탈북 화가다. 얼굴도 본명도 숨긴 채 살고 있다. "북에 남은 부모형제가 위험해지기 때문"이라고 했다. '선무'라는 가명은 '경계도 국경도 없다'는 뜻이다.

지난달 5일 행주산성 근처 작업실엔 '김일성' '김정일' '김정은'이 즐비했다. 최고 존엄은 그의 붓끝에서 우스꽝스러워진다. 백설공주, 신데렐라, 미키마우스, 팅커벨 같은 디즈니 만화 캐릭터들이 붉은 망토 입은 김정은을 포위한 그림을 그려놓곤 '벗고 놀자'란 제목을 붙이는 식이다. 북에서 배운 프로파간다(정치 선전) 미술로 그곳 지배자를 조롱한다. 선무는 "이제는 김일성·김정일이 하라는 대로 그리지 않고 나를 위한 프로파간다를 한다"고 했다. '같은 스타일로 생각만 다르게'하는 셈이다.

'천국'의 국경을 넘다

작업실에 들어서자 북한 삐라(대남 전단) 같은 포스터가 보였다. 남한 소주 참이슬과 북한 대동강맥주를 나란히 그려놓곤 붉은 바탕에 흰 글씨로 '폭탄주를 마시자'라고 적었다. "저게 '통일 폭탄주'인데 맛이 아주 좋습니다"라며 그가 커피를 건넸다.

―북한에서도 커피 드셨나요.

"커피라는 말도 몰랐죠. 맛은 지금도 몰라요(웃음)."

―왜 탈북했는지요.

"고향이 황해도인데 중국에 친척이 있었어요. 너무 배가 고파 돈이나 물건을 건네받으러 올라갔지요(1994~1998년 북한은 기근이 극심했다). 여행증명서는 함북 청진까지만 받고 숨어서 두만강변까지 갔고, 돈 받고 재워주는 민가에서 전화를 걸었어요. 그런데 중국 친척이 '국경 감시가 강화돼 지금은 위험하니 돌아가라'는 거예요. 주머니에 돈도 없고 집에 가다간 개죽음당할 것 같았습니다."

―그래서요?

"여기까지 온 김에 강을 건너보자, 무작정 떠난 겁니다. 안전한 경로를 일러줄 브로커도 제겐 없었어요."

―북한이 싫어 도망친 건 아니군요.

"과거의 저는 김일성·김정일을 위해 죽을 각오가 돼 있던 놈이에요. 그게 전부였으니까. 중국에 가서 큰 충격을 받았어요. 내가 믿었던 게 다 허상이고 가짜라니. 이젠 제가 북한에 살았다는 사실이 신기해요. 사회를 저런 식으로 끌고 간다는 게 기가 막히죠."

―중국에선 어떻게 살았나요.

"나무껍질도 벗기고 담배 수매하는 곳에서 잡일도 했어요. 잠깐이지만 건달로도 살았고요. 조선족들은 '야, 너네는 배곯잖아. 강택민(장쩌민)이 봐. 우리는 그래도 배불러' 하면서 탈북자들을 업신여겼습니다. 처음엔 '이 자식들이 제정신인가' 했어요. 북한에서 나와 보니 김일성·김정일은 욕만 먹고 잘한 게 하나도 없는 거예요."

―길바닥에 걷어차이는 자갈처럼요?

"딱 그런 꼴이었죠. 중국에서 남한 사람은 우러러보는데 북한 사람은 숨어다녀야 했어요. 남한에서 온 사업가들 주머니 털 생각을 하는 놈들도 많았습니다. 혼란스러웠어요."

―한국엔 어떻게 들어왔나요.

"중국은 싫고 불법체류자 신세라 남한 국적을 가져야겠다고 생각했어요. 라오스와 태국을 거쳐 2001년 말에 들어왔습니다. 라오스에선 감옥에 갇힌 적도 있는데 'I am from South Korea'라고 했더니 남한 대사관에 연락한 거예요. 태국에 머물 때 선교사가 '남한 사회는 혈연·지연·학연이 있어 비집고 들어가기 힘들다'고 하더군요. 저는 학연을 붙잡기로 했습니다."

"눈 감으면 북한, 눈 뜨면 남한"

홍익대 회화과 03학번으로 입학했다. 탈북자의 학비는 정부와 대학이 반반씩 댔다. 그는 "대학원은 대출받아 다녔는데 졸업한 뒤 작품이 잘 팔려 금방 다 갚았다"고 했다.

―북에서도 화가가 꿈이었나요?

"해마다 12월 31일이면 전국에서 예술적으로 재능 있는 아이들을 뽑아다 공연을 합니다. 김일성이 걔들을 격려하는 모습을 어려서부터 TV로 봤어요. 나도 미술로 지도자를 기쁘게 해드리고 싶었지요. 군복무 할 땐 우리 대대(大隊)의 역사와 김일성이 지도한 내용을 그림으로 그렸어요."

―한국땅 밟을 때 첫인상은 어땠나요?

"인천공항에 도착했는데 중국이나 태국과는 달랐습니다. 되게 깨끗한 게 먼저 눈에 들어왔어요. '국정원 가면 두들겨 패면서 조사한다'고 들었는데 그렇진 않더라고요."

―처음 정착한 곳은요.

"(충남) 공주요. 1지망은 다들 서울입니다. 저도 그랬는데 광주비엔날레를 들어봐서 2지망을 광주로 쓴다는 게 그만 공주를 적었어요."

―홍익대에서 만난 청년들은 어떻던가요.

"신입생 환영회부터 충격의 연속이었죠. 배알대로 장기자랑을 하라는데 저는 막막해서 맥주병을 깼습니다(웃음). 수강 신청도 낯설었어요. 북한과 달리 선택해야 해 괴로웠고 책임이 뒤따라 두려웠죠. 동기들이 띠동갑인데 '형, 우리 한잔해요'가 지나가는 말이더라고요. 저는 그걸 진짜로 받아들여서 오해도 생겼죠. 처음엔 김정일을 그렸습니다. 붓이 떨렸어요. 이놈을 그려야 하는데, 그게 내 전부였는데, 자꾸만 뒤를 돌아봤어요."

―왜죠?

"북한에선 함부로 김일성·김정일을 그릴 수 없으니까. 이래도 되나 싶고 무서웠습니다."

―탈북 20년이니 적응은 끝났겠지요.

"아직도 이 사회에 적응하는 과정입니다. 북에서 받은 세뇌를 쉽게 떨칠 순 없어요. 탈북자 대부분이 그럴 겁니다. 북한에도 '자유'라는 말은 있지만 정권이 그어놓은 선 안에서의 자유일 뿐이죠. 탈북 초기엔 '눈 감으면 북한, 눈 뜨면 남한'이었습니다."

―무슨 뜻인가요?

"남한에 들어와 5년 동안은 매일 북한에 가 있는 꿈을 꿨어요. 밤마다 김일성·김정일에게 쫓겨요. 눈 뜨면 한숨이 나오죠. 요즘에는 1년에 한 번 정도로 줄었습니다. 육체적인 탈북보다 심리적인 탈북이 훨씬 오래 걸렸어요."

"한국 외교, 중국에 더 당당해져야"

2015년 DMZ국제다큐영화제 개막작 '나는 선무다'(감독 아담 쇼베르그)는 그를 다룬 영화다. 명절에 색동저고리를 입은 두 소녀가 보인다. 그런데 철조망이 앞을 가로막고 있다. 이 그림 제목은 '할머니'. 선무의 목소리가 흘러나온다. "딸들이 물어요. 우리 할머니는 어디 있냐고. '윗동네'에 있는데 갈 수 없는 상황을 얘기하고 싶었어요."

―이곳에선 가족이 어떻게 되나요.

"중국에서 조선족 여인을 만났고 한국에 들어온 뒤 결혼했어요. 여덟 살, 열한 살 난 딸이 둘 있습니다."

―북에 남은 부모형제와는 연락이 끊겼나요?

"중국 친척 통해 3년에 한 번쯤 송금도 하고 소식도 들었는데 2014년부턴 단절됐어요. 중국 베이징에서 개인전 열었다가 저와 가족, 친구가 위험에 빠진 직후부터입니다. '나는 선무다'엔 그 사건도 담겨 있어요. 전시는 ×판 났죠. 개막하는 날 그림 다 압수당하고 끝났어요. 탈북했을 때 공포가 되살아났습니다."

―전시에 무슨 문제가 있었나요?

"유머러스하게 북한 정권을 풍자하고 싶었지요. 관람객은 바닥에 깔린 '김일성' '김정일' '김정은' 이름을 밟아야 입장할 수 있었어요. 중국에 사는 북한 애들이 들어올 용기가 있을까 궁금했습니다. 그런데 북한 대사관 애들이 정문에 죽치고 앉아 입장을 막았어요. 남한 대사관 사람은 코빼기도 안 보였고요. 탈북했지만 저는 엄연히 대한민국 국민입니다. 이 나라 외교가 당당하지 못하고 형편없구나 알게 됐죠. 신체적인 위협도 느꼈습니다. 가족이 중국에 다 같이 갔는데 잘못하면 북한으로 끌려가겠구나, 겁이 나고 등골이 서늘했어요."

―한국에서 살아도 여전히 이해하기 어려운 게 있는지요.

"왜 정부가 자국민을 보호하지 못할까, 하는 거예요. 불법도 아니고 공개적인 전시회에서 그런 꼴을 당했습니다. 어느 중국인이 다큐멘터리를 보고 '미안하다' 해서 제가 그랬어요. '당신이 미안할 건 없고 시진핑이 나한테 사과해야 한다'고."

―1년에 몇 점이나 그리고 얼마에 팔리는지요.

"보통 30~50점 만듭니다. 100만원짜리도 있고 3000만원도 받아요. 80%는 해외, 그러니까 교포분들이 삽니다. 전업작가가 된 직후엔 '김정일'을 많이들 사서 놀랐어요. 집에다 걸어 놓을 만한 그림은 아니잖아요(웃음)."

―병상에 누워 있는 김정일에게 소녀가 콜라를 주는 그림 '약 드세요'는 미국 주간지 타임에도 실렸습니다.

"당시에 북한은 외부의 치료가 필요한데 병이 나으려면 밖으로 문을 열어야 한다고 생각했어요. 콜라와 아디다스를 개방의 상징으로 썼지요."

―어떤 탈북 화가는 본명과 얼굴을 다 드러내는데.

"그렇게 놀더라고요. TV에 나와서 흔들거리는 탈북자들 보면 가족 모두 안전이 보장돼 있어서 저러나 싶어요."

―지금 '당신은 누구냐' 묻는다면 어떻게 답하나요.

"분단 때문에 가족을 만날 수 없는 현실, 그게 나예요. 북한도 중국처럼 개방이 필요합니다. 너무 거짓말을 많이 해놔서 문을 열면 다 들통나겠지만요."

김정은 신년사, 꿍꿍이는?

그동안 입국한 탈북자는 3만여 명에 이른다. 10명 중 1명은 북·중 국경에서 잡혀 감금되거나 처형된다. 그는 "가장 넘기 힘든 선은 이데올로기 같다"며 "세상에 있는 이념들을 다 지우고 싶어 '걸레질'이라는 작품도 만들었다"고 했다.

―최근 판문점에서 총격을 받으며 귀순한 북한 병사 소식 들으셨지요?

"죽다 살았으니 저처럼 운이 억세게 좋은 놈이구나 싶었죠."

―김정은은 무슨 꿍꿍이일까요.

"뻔하죠. 북한 체제를 계속 유지하려는 겁니다. 일단 핵을 만들어놓고 대화하려는 속셈이죠. 김정일 때 남북대화도 하고 같이 놀아봤는데 결국 재미를 못 봤잖아요. 시간 벌면서 믿을 만한 무기를 확보하려는 겁니다."

―그림들이 일종의 반어법(反語法)처럼 보입니다. 예술의 힘은 뭐라고 생각하나요.

"그림을 통해 저는 숨어도 숨은 것이 아니고 나서지 않아도 나선 것이 됩니다. 예술이 마음을 움직일 수 있다고 생각해요. 저는 북에서는 실종 상태고 남에서는 가면을 쓰고 살아요. 그림으로 말할 수 있다는 게 큰 위안입니다."

―외롭지 않나요?

"이곳에도 내 가족이 있습니다. 부모형제 그리울 땐 술을 마셔요. 언젠가 평양에서 전시회를 여는 꿈을 꿉니다. 화폭 안에 내 세계를 짓기도 하고 허물기도 하고. 북한에서처럼 당의 의도를 심는 선전이 아니라, 눈치 안 보고 내 생각과 감정을 담을 수 있다는 게 행복해요. 지탱하는 힘이 됩니다."

―이 땅에서 이루고 싶은 게 있나요?

"뭘 이루고 말고 하겠어요. 계속 작업을 하는 거죠. 가명 안 쓰고 얼굴을 드러내도 되는 날이 빨리 오길 바랍니다."

김정은은 신년사에서 '핵 단추' 운운하며 미국을 위협하면서도 평창동계올림픽 참여 의사를 밝혔다. 선무는 "김일성 때부터 해오던 수법이라 새롭지 않다"며 "그는 이득을 취하려 할 테고, 남한도 손해 보지 않으려면 외교력이 필요하다"고 말했다. 지난 9일 판문점에서 열린 고위급 회담에 대해서는 "북한 입장에선 미국과 핵 협상을 하기 위한 발판일 것"이라고 했다. 새해 소망을 묻자 문자메시지가 도착했다. "북녘의 그리움들이 안녕하기를."

Via 조선일보

Meet North Korea's Former Propaganda Artist

Sun Mu once made propaganda art for the North Korean government. Now a defector, he creates art freely in South Korea. But his exhibit was banned in China, and he has to keep his identity concealed to protect the family he left behind. AJ+'s Dena Takruri sat down with him just as tensions between North Korea and the U.S. were heating up.

via YouTube

그것이 행복이라면...展

부는 바람 / 쏟아지는 비에 / 찢기고 떨어져 나가 / 꽃잎은 / 광야에 흩날려도 / 다시 또다시 / 새싹을 틔여 / 꽃을 피우리라 / 그러면 / 우리 만나리라 / 만나서 / 얼싸 안으리라 (선무, 두고 온 그리운 얼굴들을 그리며, 남녘 서울에서, 2016년 7월 7일.) ● 작가의 개인 블로그(sunmu.kr)에 있는 글이다. 그의 절절하고 결연한 마음을 담은 모양새가 시인 못지않은 깊은 울림을 전한다. 개인적인 느낌이기도 하겠지만 선무 작가를 지근거리에서 대할 때마다, 익히 알려진 (탈북) 화가의 그것 대신 다가오는 그의 진중하고 묵직한 인간적인 면모들에 적이 놀라곤 한다. 그에게 통상적으로 따라붙는 숱한 관행적인 수식어들을 저편으로 한 채 한 인간으로서 겪어야 했던 지난한 삶에 대한 울림이 가슴에 와 닿는 것이다. 이런 이유로 종종 그의 일상적인 말과 글들이 혹은 취중진담과도 같은 호소나 여흥에서의 노래들이, 무엇보다도 그의 삶 자체가 그의 알려진 그림들보다도 더 마음에 가로 새겨졌던 것 같다. 이따금 그의 전시에서 볼 수 있는 텍스트나 설치 작업들도 매한가지이다. 작가 노트에 메모된 숱한 삶의 단상들, 그리고 힘과 기운이 가득 느껴지는 독특한 그의 서체나 이를 나무판에 꾹 눌러 새긴 텍스트 작업들에서 지난한 삶에 대한 작가의 고뇌와 열정 같은 것들이 고스란히 전해지는 것이다. 이번 전시 역시도 우리가 익히 알고 있는 선무가 아니라 지난한 삶을 살아야 했던 한 개인으로서, 혹은 그러한 우여곡절의 삶을 작업으로 이어가야 했던 작가로서 그가 겪으며 고민했던 세상에 대한 복잡하기만 한 심경들과 단상들, 그리고 그의 희망과도 같은 전언들이 독특한 설치 작업들로 펼쳐진다. 작가로서 개인 선무의 가슴에 품고 있던 마음들이나 어떤 지향들을 그나마 온전히 엿볼 수 있는 각별한 기회인 셈이다. 모두(冒頭)에 있는 그의 가슴 저린 염원을 담은 글처럼 말이다.

작가의 각별한 부탁이기도 했지만 이러한 이유들로 이번 전시는 7월 27일 정전협정일에 맞춰 개막한다. 정전협정일은 1953년 7월 27일, 한국 전쟁의 정지와 최후적인 평화적 해결이 달성될 때까지 한국에서의 적대행위와 일체의 무장행동의 완전한 중지를 보장하는, 이른바 한국의 군사정전을 확립한 목적으로 국제연합군과 북한군, 중공인민지원군 사이에 맺어진 협정일이다. 이 협정으로 인해 남과 북의 적대행위는 일시적으로 정지되지만 전쟁상태는 계속되는 국지적 휴전상태에 들어갔고 남북한 사이에는 비무장지대와 군사분계선이 설치되었다. 역사적인 날임에도 불구하고 그 긴 세월의 간극이나 여타의 이유들로 인해 많은 이들이 잊고 있었던 이 날을 작가는 또렷이 가슴에 기억한다. 그리고 아직도 이러한 실질적인 정전이 완성되지 못하고 있음을 주시하면서 이를 못내 기념하고 싶었던 모양이다. 그렇기에 이 의미심장한 기념일을 각인시키려 하는 이번 전시는 남북의 화해와 통일에 대한 작가의 염원의 장이자 그가 그간의 숱한 그림으로 차마 못다 했던 바람들을 전하는 자리이기도 하다. 이러한 뜻 깊은 맥락에서 이번 전시의 전체적인 얼개가 가로 놓여진다. 작가의 인식처럼 아직 우리는 완전한 평화의 장에 놓이지 못한 분단국가이고 이러한 분단의 상처와 흔적들이 사회 곳곳에 자리하고 있기 때문이다. 하지만 작가의 이러한 입장을 굳이 정치적으로 해석하기엔 무리가 있어 보인다. 작가에게 남과 북이라는 체제 분단의 역사는 사회 전체의 그것이기 이전에 한 개인의 삶에 드리운 어떤 뼈아픈 상처와 아픔들이고 두 개의 체제, 국가에서 삶을 살아야 했고 서로 다른 이데올로기를 넘나들면서 작업 활동을 해야 했던 작가 개인으로서 어쩔 수 없이 부딪히고 고민해야 했던 문제들이었기 때문이다. 이번 전시의 설치 작업의 텍스트로도 활용될, 작가의 노트에 빼곡하게 망라되어 있는 서로 다른 두 체제에 대한 작가의 개인적인 단상들이 이를 증거 한다.('Korea의 풍경') 그가 북한과 남한의 일상을 살며 세세히 느꼈던 그 숱한 차이들의 목록 속에서 우리는 그가 얼마나 두 체제를 뼈저리게 겪고 느끼고 고민했었나를 짐작하게 된다. 그리고 여기에 더해 작가가 채집하고 기록한 남과 북의 갖가지 관행화된 정치적인 선전 문구들과 이를 바탕으로 화해와 통합의 의미를 가시화시키고 있는 설치 작업도 두 체제를 가로지르려 하는 작가의 단상들과 소망을 담아낸다. ('Game') 이들 서로 엇갈린 텍스트들은 남과 북의 거시적인 이데올로기상의 차이뿐만 아니라 미시적인 일상의 삶마저도 가로막고 있는 차이들을 담고 있으며 동시에 정치적이고 사회학적인 개념상의 차이를 넘어 작가의 지난한 삶 속에서 각인되어야 했던 삶의 차이마저 포함하고 있다. 단지 서로의 다름을 용인해야 하는 그런 차이가 아니라 서로를 겨누고 질시하는 그런 차이, 서로에게 상처가 되고 아픔이 되는 차이였기에 작가는 이들 서로 다른 차이들을 봉합하고, 가로지르려 한다. 이번 전시에서 작가가 전하려 한 어떤 지향성 혹은 한 개인으로서 세상을 향해 던지는 소망의 실체들이다. 그렇기에 전시장을 가득 메우고 있는 남과 북의 각기 다른 텍스트들은 그 서로 다른 체제 속에서의 삶을 몸소 체험해야 했고 이를 스스로의 삶으로 통합하려 했던 작가로서 고민했을 삶의 오만가지 번뇌 같은 것들이었는지도 모르겠다. 작가는 마치 수행이라도 하듯 이러한 삶의 고민과 번뇌들을 조목조목 상기하고 가시화시키면서 이를 엮고 이어간다. 그 서로 다른 차이를 끊임없이 이어가면서 무화시키는 것이다.

선무(線無), 그의 예명(藝名)처럼, 하나의 삶을 두 개의 체제로, 국가로, 이데올로기로 분리시키는 저 단단한 차이의 선들을 지우고 봉합시키려 하는 것이다. 마치 그동안의 작가로서의 그의 삶이 그런 것처럼 말이다. 이는 그의 작업의 지향이자 동시에 개인으로서의 삶의 내면의 움직임 같은 것들이기도 할 것이다. 그렇기에 그를 흔히들 지칭하는 '탈북'이란 레테르는 옳지 않은 것일지도 모르겠다. 단순히 지리적이고 공간적인 삶의 이동으로 그를 설명하기엔 그의 지난한 삶의 지난한 궤적이 훨씬 복잡할 뿐만 아니라 남북과 좌우 같은 이항대립(binary opposition)을 넘으려 하는, '탈, 경계'인으로서의 면모가 더 두드러지기 때문이다. 이번 전시에서 볼 수 있는, 이들 통합의 전언들을 담고 있는 설치 작업들도 같은 맥락에서 읽혀진다. 그저 통일이라는 거창하고 요란한 정치적인 구호나 상징으로 전해오는 것이 아니라 작가 개인의 지난한 삶에서 숱하게 마주해야 했던 내면의 고민들과 이를 애써 극복하려는 절절한 마음들로 읽혀져야 할 것이기 때문이다. 그렇기에 이번 전시에서 볼 수 있는 서로 다른 국가 체제들을 외시하는 갖가지 상징들도 단순한 외연적인 의미들을 넘어선다. 그렇게 일면적으로 해석하기에는 그의 지난한 삶의 궤적을 통해 겪었을 개인적인 내면의 상처들이 너무도 크지 않았나 싶다. 그가 힘겹게 걸어온 삶만큼이나 그는 한낱 정치와 이데올로기의 또 다른 피해자일수 있으며 그러한 복잡다단한 삶의 상처와 희망의 이야기들을 작업으로 봉합시켜오면서 작가로서의 삶을 펼쳐가고 있기 때문이다. 작가의 말처럼 그는 온전히 자신을 향해 뛰는 심장이 있는 선무일 뿐이니 말이다.

그렇다. 그는 선무라는 한 작가이고 뜨거운 가슴을 품고 있는 한 개인일 뿐이다. 그에게 유독 실존적이고 존재론적인 면모가 도드라지는 것도 어쩌면 그가 지구상 유래 없는 서로 극명히 다른 두 체제의 국가를 몸소 경험한 작가였기 때문일 것이다. 하지만 이러한 서로 다른 체제 또한 그저 외적인 맥락일 뿐, 이들 두 다른 체제에 관한 것들만으로는 작가 혹은 개인으로서의 선무를 온전히 설명하지 못한다. 이러한 면모를 다른 측면에서 살펴볼 수 있는 작품이 이번 전시를 통해 일부가 소개되고 이후 공개될 애덤 쇼버그(Adam Sjoberg)의 '나는 선무다 I AM SUN MU'라는 다큐멘터리 영화이다. 2014년 베이징의 한 미술공간에서의 개인전을 둘러싼 에피소드를 담은 이 영상은 견고한 이데올로기 지형 속에서 작가로서의 험난한 삶을 여지없이 보여준다. 아울러 정치적 목적을 최대한 배제한 채 예술이 가진 보편성을 토대로 분단의 특수성과 북한의 현실을, 그리고 선무의 통일에 대한 염원과 소망을 담은 메시지를 전한다. 하지만 결국은 중국 공안과 북한의 방해로 개인전이 무산되어야 했던, 현실의 작가가 처한 상황을 고스란히 가시화시키면서 작가를 둘러싼 체제, 이데올로기의 모순 또한 여지없이 보여준다. 그저 자신의 삶에 각인된 체제의 모순을 드러내면서 절실한 마음으로 이에 대한 해결을 염원한 작가에게 현실이 남겨야 했던 상처들이다. 그는 말한다. "남과 북의 화해와 평화를 이야기 하는 것이'죄'가 되어 돌아오고, 세상의 평화를 이야기 하는 것이'죄'가 되어 돌아오고, 이 세상사는 사람들의 이야기를 하는 것이, 내가 살아온 삶과 앞으로 살아갈 미래를 이야기 하는 것이'죄'가 되어 돌아왔다고" 어쩌면 이러한 모순적인 상황 속에서 그 내면의 실존을 향한 지향성 또한 더욱 커졌던 것이 아니었을까 싶다. 그렇게 자신의 일거수일투족을 정치적이고 이데올로기적인 그것들로만 보는 세상에 대해 그는 단지 자신의 삶일 뿐이라고 강변한다. 그리고 이러한 세간의 왜곡된 시선들조차 개인의 삶으로 작가의 삶으로 굳게 다져가면서 세상을 향해 외친다. "이제 조금 알 것 같습니다 / 그것이 행복이라면 행복하지 않겠습니다 / 그것이 전부라면 살 생각이 없습니다 / 그것이 아닌 나를 알았습니다 / 이제 세상에 대고 소리칩니다 / 나는 선무라고"

설령 그것이 행복이라 할지라도 행복하지 않을 것이라는 작가의 외침은 단호하기만 하다. 묘한 뉘앙스를 가지고 있는 이 외침은 아마도 작가가 거대한 체제가 꿈꾸는 집단의 행복이나 혹은 개인의 사적인 욕망만으로 채워지는 그러한 행복이 아니라, 다시 말해 체제와 이데올로기에 정향된 그런 행복이 아닌 개인의 충일한 삶의 지향과 만족에서 삶의 행복을 찾으려 했기에 그렇게 외쳤던 것이 아니었을까 싶다. '그것이 아닌 나(를 알았습니다)'는 결국 체제와 이데올로기로 규정되지 않는 나를 의미하는 것일 수 있기 때문이다. 만약 그렇다면 이는 비단 선무만이 아닌 우리 모두에게 해당되는 외침이기도 할 것이다. 어쩌면 우리 역시도 線無(선무)처럼, 우리 스스로를 외적인 잣대로 규정하는 것들을 가로지르고, 무화시키는 삶을 향해 나야가야 할 것이기 때문이다. 그런 면에서 그의 작업은 분단이라는 현재 혹은 과거 저편에 자리하는 것이 아니라 그러한 체제 모순이 극복이 될, 저 근 미래의 어떤 지평에 자리하는 것일지도 모르겠다. 그렇기에 그의 염원과 소망은 온갖 미디어상의 서로 다른 이유로 외치고 있는 구호와 이데올로기로서의 통일이 아닌, 그 서로 다른 체제를 몸소 체험하고 고민하면서 힘겹게 체득된 것들이며 그리고 무엇보다도 그 분단체제의 아픔을 개인사의 내면적인 번민들로 고뇌해야 했을 한 개인으로서의 절절한 마음에 다름 아닐 것이다. 그리고 그러한 모순된 경계들을 가로지르고 넘어서고자 하는 한 작가로서의 외침이 아니었을까 싶다. 그런 이유로 대안공간 루프에서의 이번 전시 또한 작가의 익히 알려진 그림만을 소개하는 그런 전시가 아니라 작가가 간절히 염원하고 소망해왔던 마음들을 담아 전하려 했던 것 같다. 같은 땅에서 한 하늘을 보며 함께 살아가고 있는 그와 우리가 동시에 다가서야 할 진정한 행복을 위해서 말이다. 그렇게 이번 전시는 작가 개인의 삶의 궤적에서 꾸준히 지향해 온 절실한 소망을 담고 있어 뜻 깊은 의미를 가질 뿐만 아니라 이런 이유들로 인해 동시대 작가들의 여느 공간적 설치 작업들과도 구별된다. 아무쪼록 이번 전시가 우리가 처한 이 남다른 현실은 물론 작가가 전하는 간절한 희망의 전언들이 모두에게 공감되는 뜻 깊은 장이길 기대해 본다. ■ 민병직