A North Korean defector sees his art silenced in China

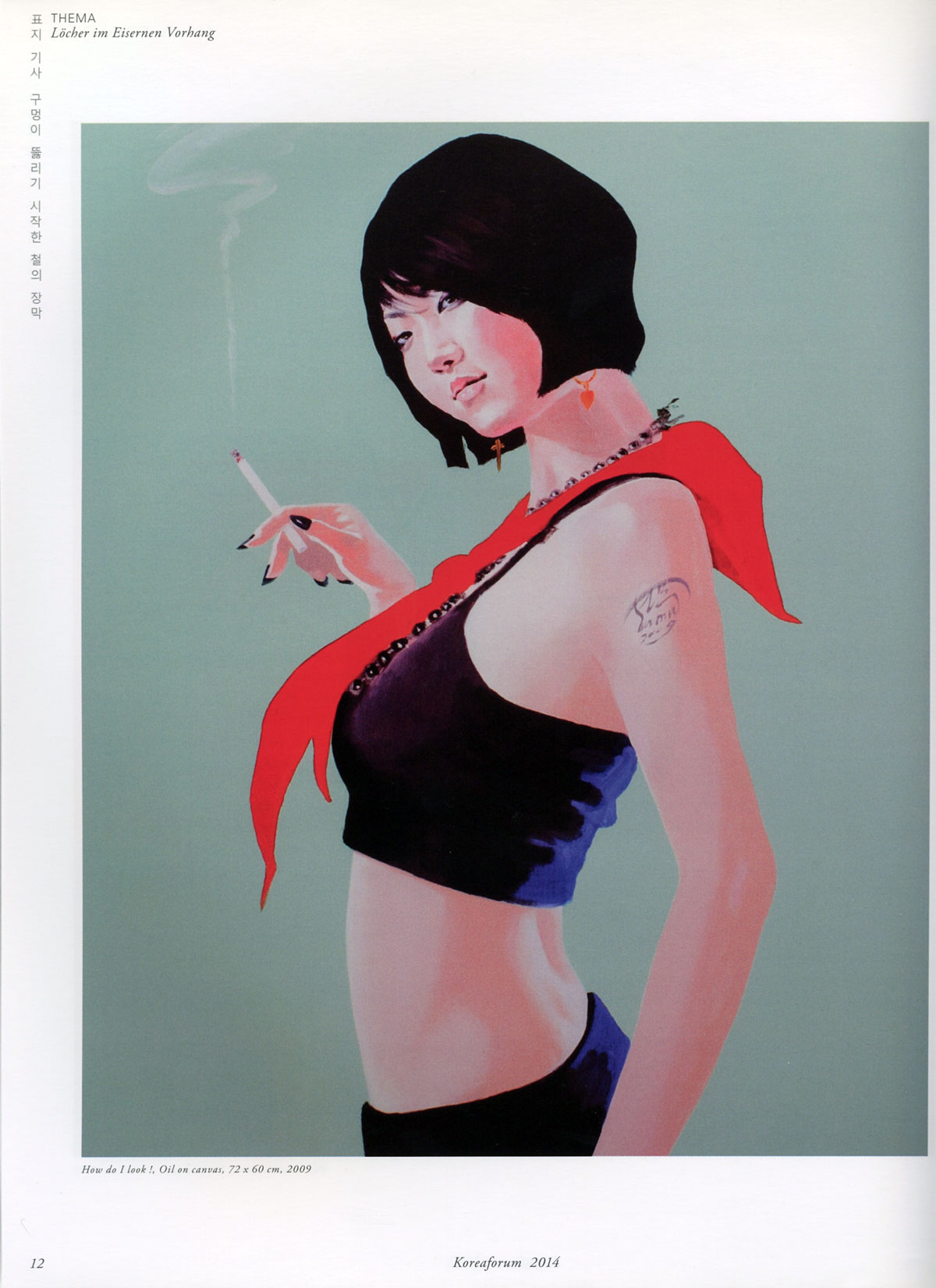

Sun Mu's paintings satirize the Pyongyang propaganda he once produced

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/36252322/4_cmbbbb.0.jpg)

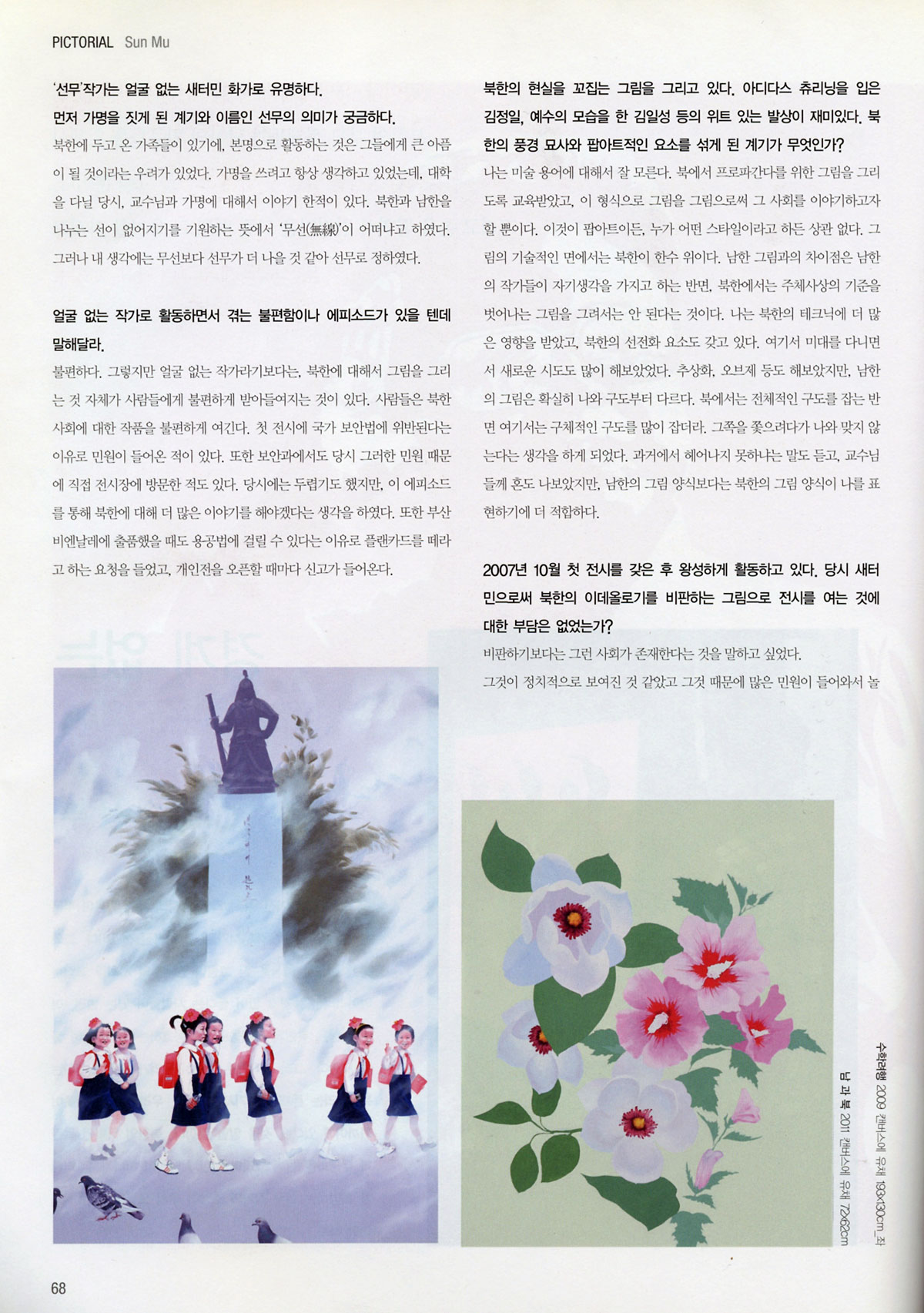

Look at us, by Sun Mu. The text translates as, "Let us endure hardship with a smile!"

An exhibition of works by a former North Korean propaganda artist was cancelled this week in China, reportedly under orders from the Chinese government. As AFP reports, Beijing's Yuan Dian gallery was planning to show a collection from Sun Mu, a North Korean defector who uses a pseudonym for fear of retribution from Pyongyang. The month-long exhibition was due to open on July 27th, but according to South Korea's Yonhap news agency, Chinese police blocked people from entering the gallery and removed Sun Mu's paintings just before the opening.

Officials gave no reason for the closing, though China has a long history of censoring both media and art, and it remains North Korea's most important ally. China is North Korea's biggest trade partner, supplying the isolated dictatorship with food and oil, though there have been signs of strain between the two countries since Kim Jong Un ascended to power in Pyongyang. The exhibition scheduled to open in Beijing this week was titled "Red White Blue" — a reference, organizers said, to the national colors of the six countries involved in talks over North Korea's nuclear program.

Sun Mu, for his part, said simply that the Beijing exhibition was "not being held as planned," and declined to give further details. "I need to figure out the situation first," the artist told AFP. "I can't talk too much right now."

Sun Mu fled North Korea in 1998 and settled in Seoul in 2001. He grew up singing songs of praise for the Communist regime and, while serving in the army, was trained to create propaganda posters for the government. Much of the work he produced relied on familiar tropes — images touting North Korea's military might, coupled with impassioned slogans calling for citizens to defend their leaders at all costs.

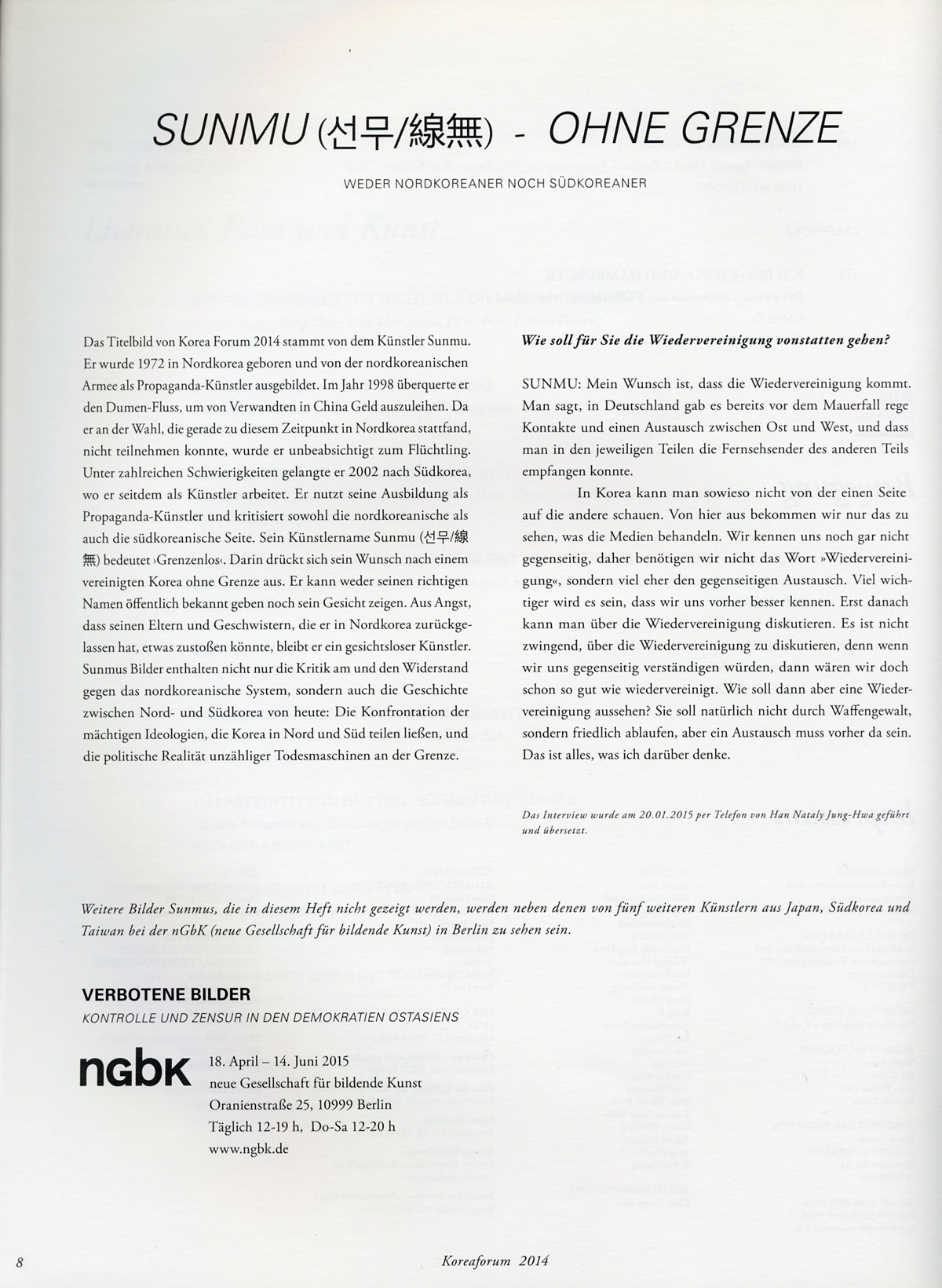

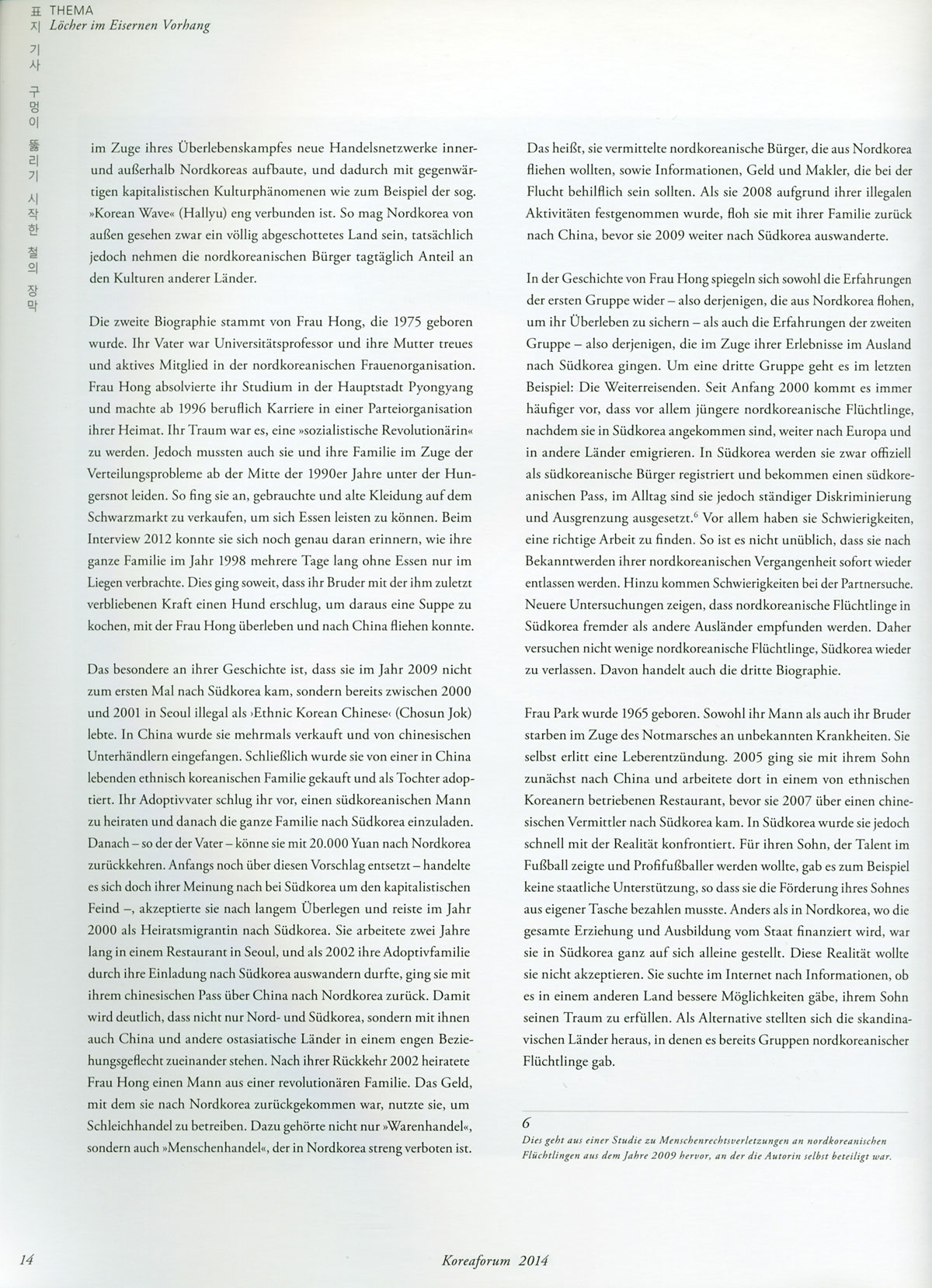

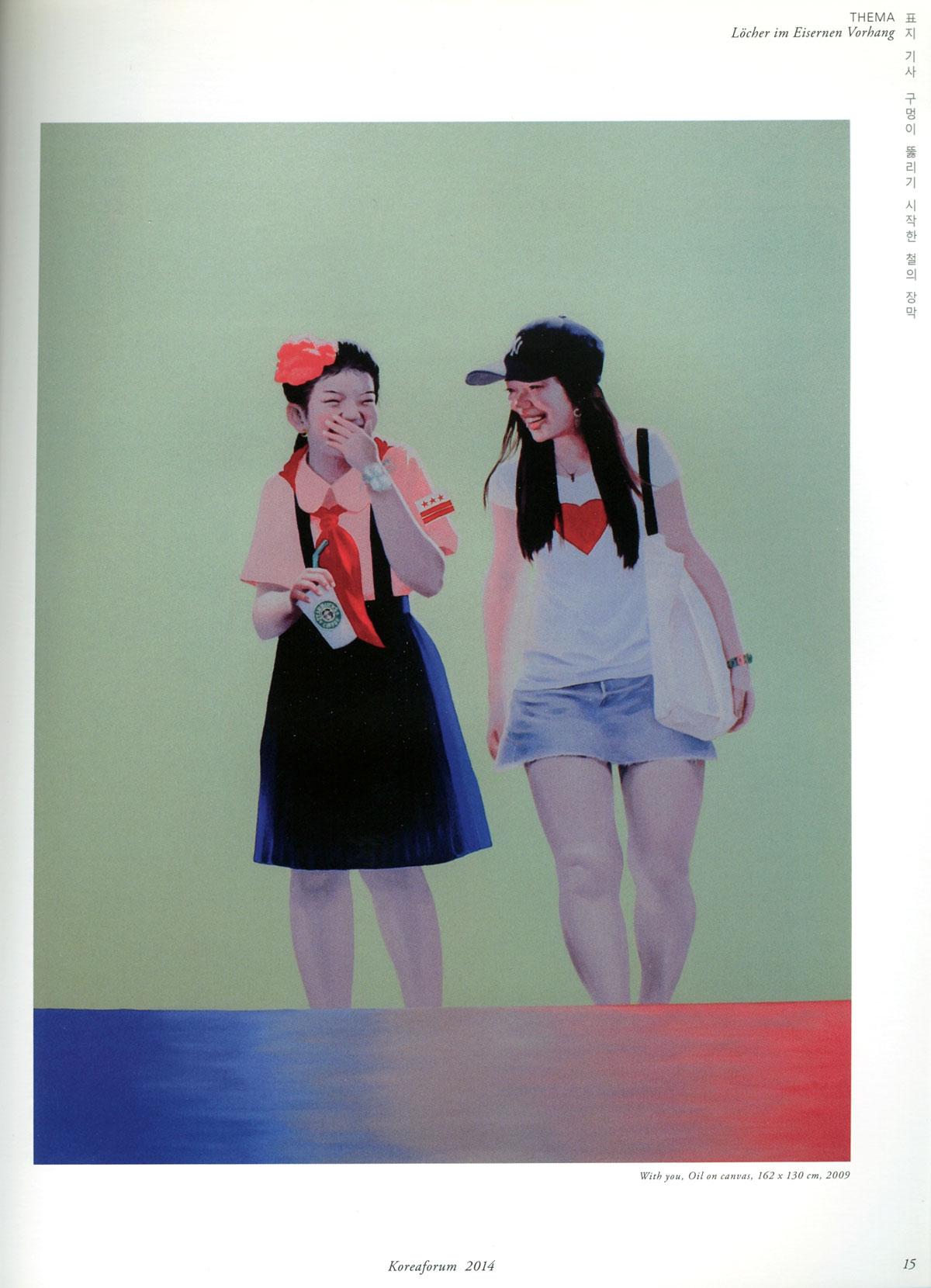

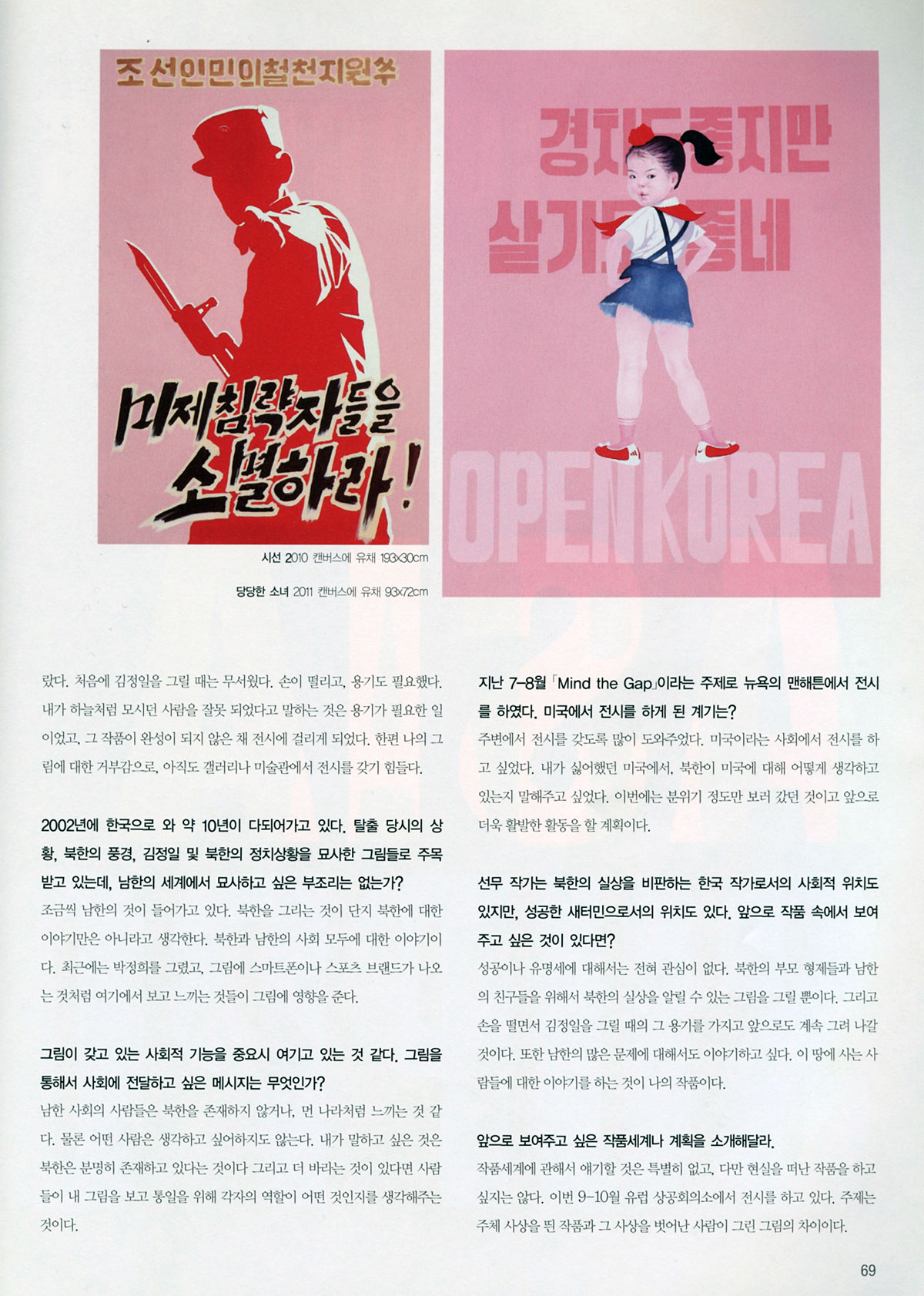

He decided to escape following a devastating famine during the mid-1990s, and soon embarked on a more subversive artistic path, producing satirical paintings in the same propagandistic style he had come to know so well. One features an image of the elder Kim wielding a knife, a maniacal grin spread across his face; others include bold slogans like "Open Korea." Some are more subtle in their commentary on the notoriously hermetic state — a North Korean schoolgirl screaming with joy while listening to an iPod or drinking Coca-Cola.

Sun Mu's works were met with some confusion at first; when he exhibited paintings in Seoul in 2007, some interpreted it as true Communist propaganda, and alerted South Korean authorities. His irony has become more apparent, though, and today his paintings reportedly fetch as much as $20,000 a piece.

Yet Sun Mu continues to shy away from the limelight, for fear that revealing his identity may jeopardize the safety of his relatives in North Korea. In South Korea, he's known as the "faceless" painter because of his refusal to be photographed.

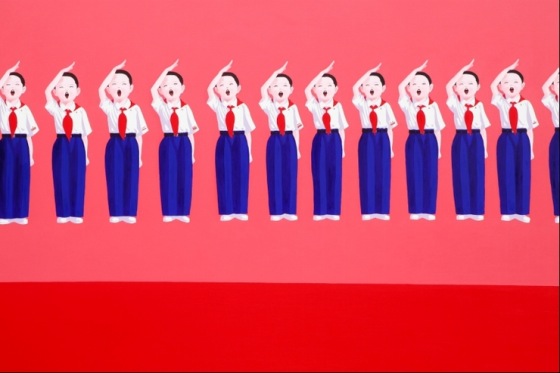

To date, his most famous work is Happy Children — a series of paintings of North Korean schoolchildren wearing identical smiles. The figures are chilling in their uniform, robotic glee, but Sun Mu says they're very much rooted in reality.

"They teach you how to smile that regimented smile — there’s a certain way to shape your mouth," he told the New York Times in 2009. "We children thought we were happy. We didn’t realize that our smile was fabricated and manufactured."

Via THE VERGE

Sun Mu – the faceless painter

Sun Mu is not the artist’s actual name. It’s a nom de plume that uses a combination of two Korean words that translate to ‘The Absence of Borders’. It not only represents what he feels is the transcendence of art but also the literal military demarcation line that keeps the Korean people separated.

THE RAIN had just stopped falling when I arrived at Sun Mu’s small art studio atop an old industrial building in one of Seoul’s western districts. His wife, Jeong and their two daughters, ages 5 and 2, had dropped by and stayed awhile longer to avoid the unpleasant weather.

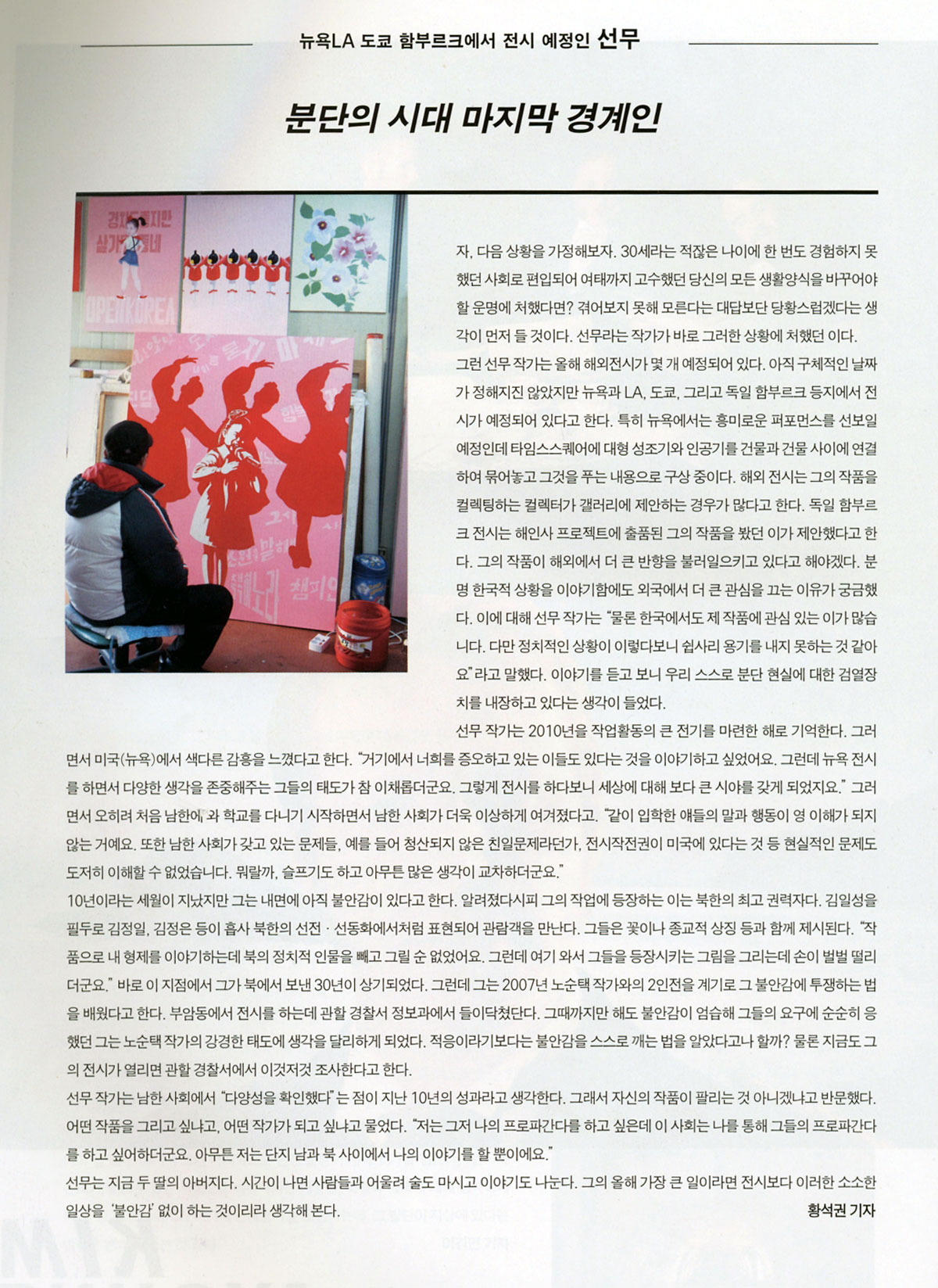

Standing inside the studio, we’re surrounded by stacks of vividly colored paintings: some depicting smiling schoolchildren, another the silhouettes of dancers colored in blood-red and hanging on the back wall. a portrait of the late North Korean ruler Kim Jong-il.

Some of these images, while out of place if not illegal in democratic South Korea, reflect Sun Mu’s life story. It’s a complicated history that stretches back to his childhood in North Korea.

“When I saw Kim Il Sung on TV being pleased with the writings and paintings of little kids, I was really impressed. I wanted him to pat me on the back. I wanted his praise,” Sun Mu said. “I wanted him to like me too.”

Sun Mu has not seen his family since late 1990s. Even though his hometown would be just a few hours drive from where he lives now, it might as well be on another planet. As a defector from one of the world’s most repressive nations, Sun Mu can never go back.

Separated by the landmine filled DMZ since the end of the fratricidal Korean War in 1953, travel between the two nations is all but forbidden. There is no phone or postal service. And given the state of tensions now on the peninsula, there appears to be no change on the horizon.

Sun Mu’s story is not of a man whose questioning of the system led him to seek freedom. Unlike in George Orwell’s novel 1984, Sun Mu did not come to a revelation that what he had grown up believing was all a lie. Instead he like most of the other 23,000 North Koreans that now call South Korea home, never actually intended to leave his family for good.

When Sun Mu arrived in Seoul in 2002, he only knew one thing: how to paint. He had been trained as a propaganda artist back in the North and didn’t want to give up his trade, even though he was unsure how he could make this style relevant in his new surroundings. After time, he realised that same motif he once used to glorify North Korea’s leaders on banners and posters back home could be used to create an ironic critique of the same men he once worshiped like gods.

“In North Korea art exists to promote political propaganda. And North Koreans exist to promote the regime. Now my mission is to describe how life is for North Koreans, how painful it is through art.”

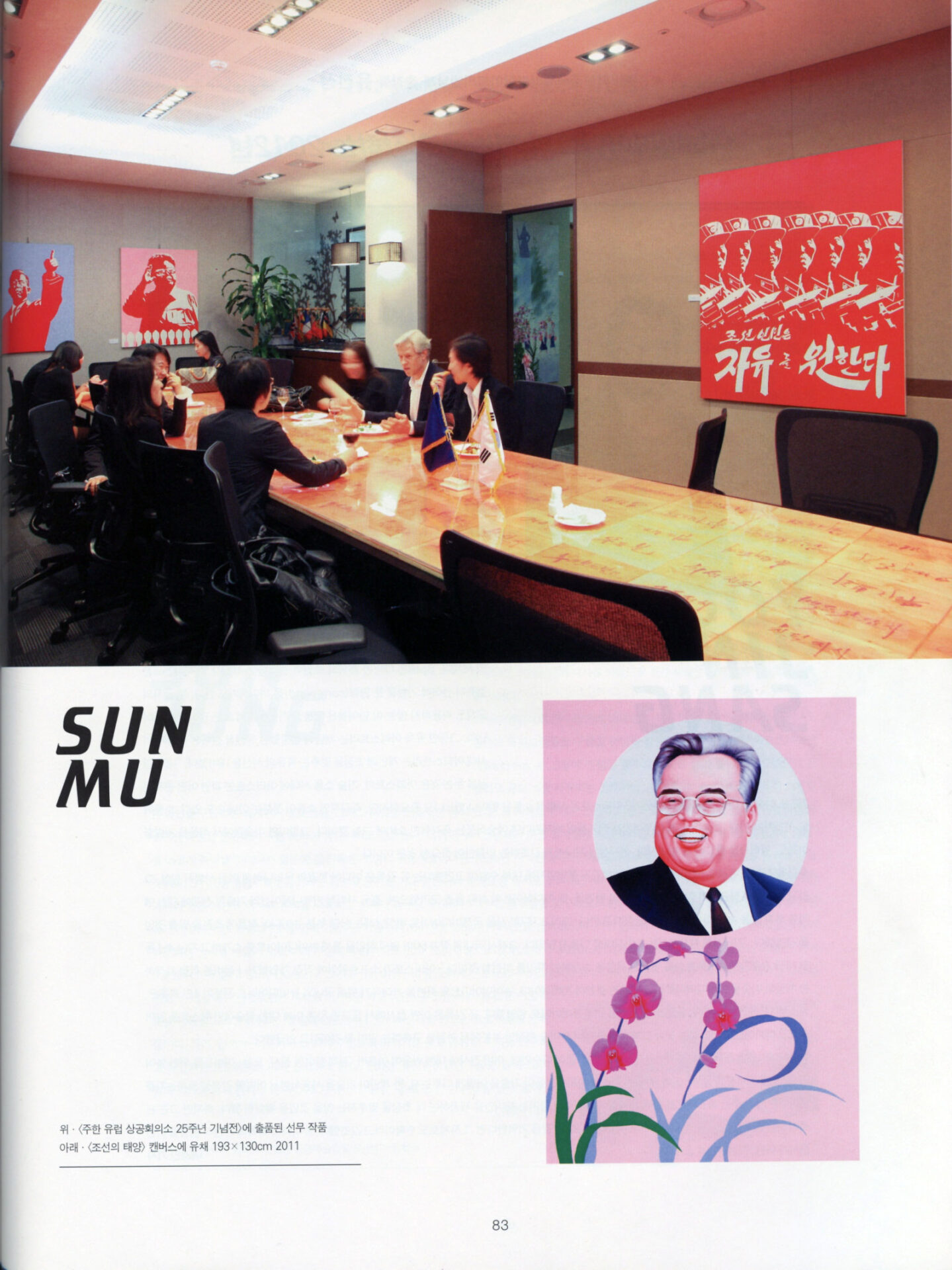

Since his first exhibition in 2007, Sun Mu has gained international recognition. He’s been invited to present his work at galleries in Germany and Australia. Of all his works, the portraits of his former ruler Kim Jong-il, dressed in colorful track suits, have brought him perhaps the most attention.

Making something like that would have been unthinkable back home.

“You don’t even need to go to a court, you are executed right away,” Sun Mu said while gliding his hand across his throat. “If you play with the face of the leader, you are done.”

‘The Faceless Painter’

Sun Mu is not his actual name. It’s a nom de plume that uses a combination of two Korean words that translate to ‘The Absence of Borders’. It not only represents what he feels is the transcendence of art but also the literal military demarcation line that keeps the Korean people separated. But it’s not only for artistic effect that he goes by this handle: it’s to protect the people he left behind.

South Korean media dubbed Sun Mu ‘The Faceless Painter’. That’s because he refuses to have pictures taken of him straight on. He’s worried that if his real name and image gets back to the North Korean authorities, his family will be punished for his crimes. And whenever showing his artwork at galleries, Sun Mu pulls a brimmed cotton hat down over his face.

“It covers my face just enough. I’ve been wearing it since my first exhibition. I do it out of concern for my family in North Korea,” he said.

Sun Mu’s fear for the safety of his loved ones is not without reason. For decades North Korea has implemented a three-generations rule that punishes a law-breakers’ entire family if the crime is seen as an affront to the state. Defection alone is punishable by death. Sun Mu’s new career as a critic of the regime would without doubt be regarded as one of the most treacherous of offenses.

Although he goes to great lengths to conceal his face, Sun Mu is a handsome man in his late 30s. Sun Mu can look very stern one moment, but when a smile begins to form his face illuminates. His wide smile reveals a boyish charm, which considering what he’s been through, might seem amazing.

But as Sun Mu explains, no matter what the circumstance, all North Koreans know how to smile.

Smiling for the Great Leader

“She is smiling too much. It’s an organised and fake smile.”

For six decades, the Kim family has ruled North Korea with an iron fist. At the end of World War II the Soviets, who ceded control of the northern half of the peninsula, chose the guerilla fighter Kim Il Sung to lead the newly formed Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), the nation’s official name. Kim would go on to launch the surprise attack in June 1950 that ignited the 3-year long Korean War. Millions of Koreans from both sides lost their lives and tens of thousands of families are still divided today. Combat only ended in a cease-fire agreement.

A personality cult was formed around Kim. He was credited with single handedly driving away the Japanese in 1945 after their 35-year colonisation of Korea as well as successfully keeping the imperialist Americans at bay with their puppets in South Korea. Kim became known as the Great Leader and father of the Korean race. The same cult of personality has been inherited by his son Kim Jong-il and grandson, North Korea’s new leader Kim Jong-un. Sun Mu was not unlike any other child growing up in the DPRK.

Sun Mu recalls drawing pictures of flowers and bamboo trees as a child. His family and teachers noticed he had a knack for painting. By age 12, Sun Mu was chosen to receive special guidance from his elementary school’s art teacher, who he lived with for six months at the school.

“The teacher said that observation is the most important skill for an artist. You have to look at the subject and find its interesting characteristics,” Sub Mu recalls. “You see an object for a moment, you have to take as much from it as you can and then draw it as accurately as possible.”

Throughout his teen years, Sun Mu used those lessons to improve his skills. He’d climb to the top of hills overlooking his town and draw landscapes. He recalls dropping by train stations and sketching the passengers waiting to board. Sun Mu credits this teacher with giving him the foundation for his artwork.

“I had a part time job while I was in university here in Seoul. My friends and I had to paints murals on the sides of some walls, pictures like birds and trees. But while my friends painted imaginary looking trees, I painted really realistic ones, like pine trees. The owner of the wall was impressed with my attention to detail. He let the other guys go and hired me to finish the mural all on my own.”

Painting realistic images might have been the only practical lesson Sun Mu received from his education. He says he thought he knew a lot about the outside world, but acknowledges that at the time he was only taught countries’ names and nothing about their people or history, let alone their art. No one knew that beyond North Korea’s borders, other Communist regimes were falling and that South Koreans were wealthier, better educated and ate three meals a day.

Sun Mu doesn’t get upset about his lost childhood. He and every other North Korean child had no idea what they were missing. But he tries to convey this hollow happiness in his work today.

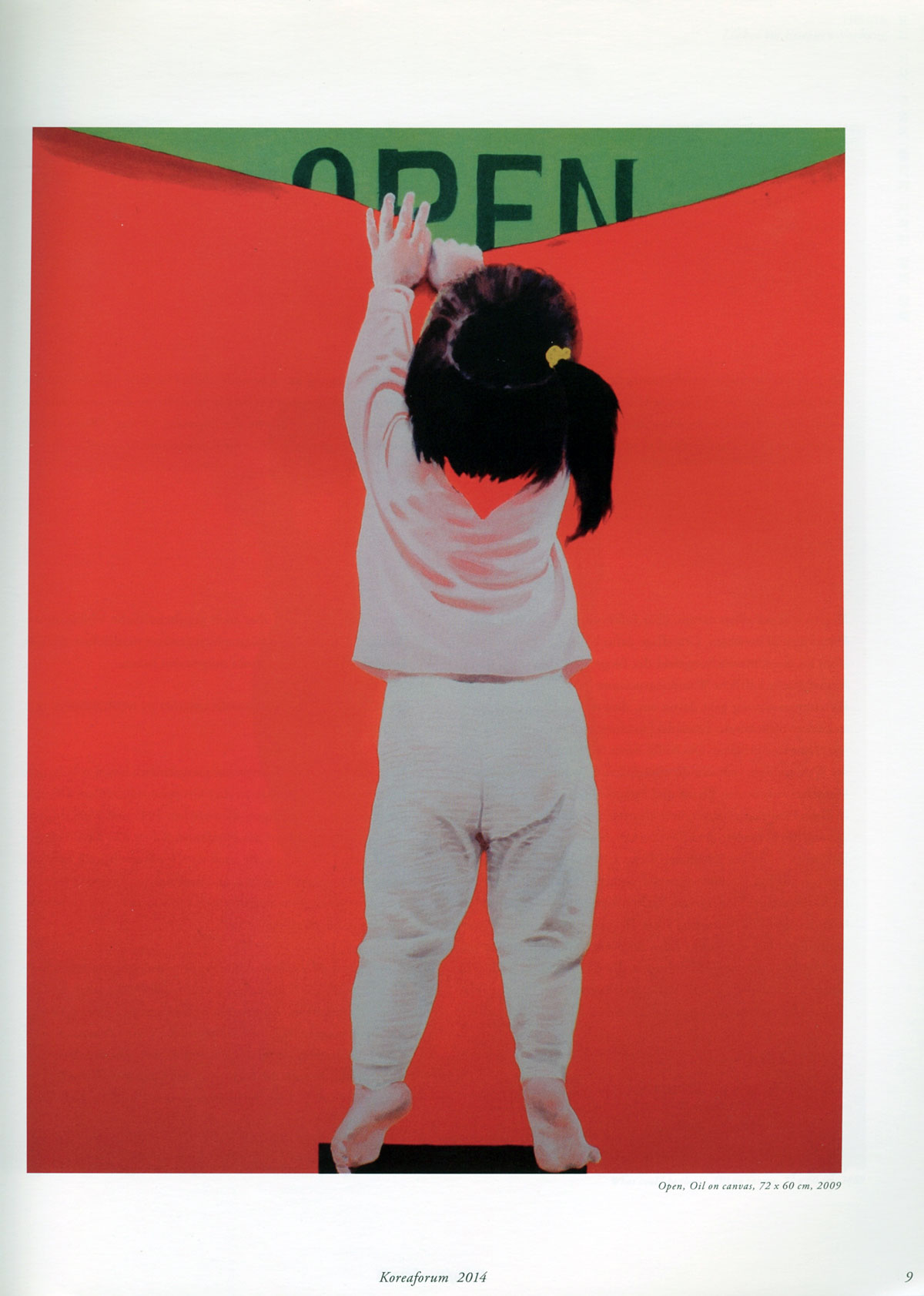

Sun Mu’s paintings of children are some of his most striking pieces of art. They are portrayed with wide-open eyes and ear-to-ear smiles, often dressed in North Korean school uniforms or traditional costumes. At first glance they look happy, but look closer and they seem miserable.

“I was educated to smile like this when I was a child too. I thought I was happy. But after I came to South Korea, I realised it wasn’t real happiness.”

Intuition artist

Sun Mu hands me a book, a collection of some of the paintings he’s done since coming to South Korea. There are portraits of accordion playing soldiers, a little girl holding a bouquet of flowers, a pudgy baby boy in blue suspenders: all with that same unbelievably eerie smile. These pictures are a far cry from the images Sun Mu painted back in the North.

“One of the paintings I made that hung on the walls in some schools there was of a North Korean student in his school uniform. He was stabbing a pencil through an American soldier. That pencil then went through the body of a Japanese soldier standing behind him,” Sun Mu recalls with a smug laugh. “On the painting was the slogan ‘Let’s Study As If We Are Stabbing Americans’.”

That is a typical example of the kind of propaganda art that is found all over North Korea. From an early age, children are indoctrinated to hate the United States, which Pyongyang blames for keeping the peninsula divided. These banners and murals are violent and bloody and were what Sun Mu did best.

But he didn’t receive any special training on how to create these types of paintings. He was never shown examples of propaganda from the USSR, Cuba or East Germany to serve as a model. As he explained, artistic education in North Korea is a matter of copying what has already been done.

“The government holds a contest amongst professional propaganda artists. They spread the art around the country. All we did was copy that kind of style. Of course the outcome is different, but we just copied what we saw.“

Artistic inspiration was also taken from one’s surroundings. After high school, Sun Mu was accepted into a specialised school for iron welding. He also was the head of an extracurricular art club where he and classmates drew more propaganda posters. The floor of the school’s foundry became the backdrop for many of Sun Mu’s works at this time.

“These kind of paintings are called intuition art, because you draw what is in your immediate sight.”

Key to all North Korean propaganda is the slogans. Sun Mu would attach grandiose phrases to his art like “We Can Go Our On Way,” a reference to the state’s political ideology of self-reliance, called juche. He says he was never worried that the pieces he created wouldn’t be good enough.

“Your teachers give you the phrases, you can’t modify them. Basically you just take what you have seen from another poster and apply the phrases. So you really couldn’t do it a wrong way.”

Sun Mu decided to leave the welding school and complete four-years mandatory military service. His unit was in need of it’s own propagandist and once his senior officers learned of his talents, Sun Mu was conscripted to become their official painter. This was the point when his art took on a darker tone.

“I had to add some more violent imagery, scenes of destruction, more power and energy to the type of art that I had already been making.”

It was by now that Sun Mu knew he had what it takes to become a nationally recognised propaganda artist. He aspired to join the government commissioned troupe that made the regime’s official art, the Mansudae Art Studio. After finishing his military duty he was accepted into an art school and was on his way to achieving his dream.

Sun Mu says there wasn’t much left for him to learn about making intuition art. The school was more of a chance for him to network and make connections for what he planned would be his career. There were classes on the role of the artist in North Korean society- to serve the promotion of juche and honor the nation’s leaders. Sun Mu also took a course in Western Art History, but says in hindsight, he didn’t really get much out of it.

“We learned about Leonardo Da Vinci, Michelangelo, the Last Supper and the Renaissance, but we never actually saw any of these paintings.”

Any Western ideals of romantic art were lost on Sun Mu. But that didn’t matter to him. He was getting praise from his teachers for his work. In fact, that was about all the feedback he received. Students did not talk to one another about their projects or ideas. There were no critiquing sessions or opportunities for students to learn new techniques to improve their craft.

Like the manufactured smiles in Sun Mu’s paintings of children, art was an emotionless expression. The militant top down nature of North Korea did not encourage students to experiment with new concepts or designs. And according to Sun Mu, fear was a major factor in preventing artists from exercising creativity. “In North Korea, becoming it’s impossible to be an outlier. If you try something beyond the frame of what you have learned from your teachers you will go to jail. Everyone knows that. There are very specific guidelines to follow and if you don’t, you are removed, no matter how good you are. That’s how the system has worked for over half a century. People are used to it. So you don’t even think about doing something different.”

Under these conditions, censorship was not an issue. Sun Mu and his classmates had a clear understanding of what was expected of them in order to please Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong-il. Ironically, it wouldn’t be until a decade later, in South Korea, when Sun Mu was painting portraits of the two North Korean rulers that he would be confronted with outright censorship.

No regrets

“In front of the river there are bushes and trees. I was waiting there to cross the river at the right moment. When I was waiting, even the sound of insects was loud to me. What would’ve happened if I had stepped on a branch and made a noise? Soldiers would have probably come and killed me.”

When I asked Sun Mu what he missed most about North Korea, he leaned back and took a few moments to respond.

“There are a lot of things I miss,” he said. “My family, my friends.”

But soon that boyish grin returned to his face as he recalled a memory from his childhood.

“My friends and I would go fishing in the river in my hometown. We’d make porridge out of the fish we caught.”

Sun Mu then went into another story, at a rapid pace, laughing as he recounted it.

“One time my friends and I wanted to throw a barbecue party for some other guys who were coming back home from the army. We wanted to grill four dogs, but needed 50kg of corn to barter for them. We didn’t have enough so I stole a bag of rice from a warehouse that I was working at and we were able to get the meat.”

The fact that food accounts for some of Sun Mu’s favorite memories about life back in the North is not surprising. By the time Sun Mu was finishing up art school, North Korea had plunged into famine. There is no reliable data on how many people actually died during this time in the mid to late 1990s, but aid groups’ estimates range anywhere from 800-thousand to 2-million.

The loss of support from the Soviet Union, consecutive years of bad weather and the death of Kim Il Sung in 1994 broke down North Korea’s food distribution system. The signs of mass starvation could be seen all over Sun Mu’s town. He remembers spotting an old woman lying on the dirt outside the town market waiting to die. Beggars at the local train station were too hungry and weak to even move. Many people in his town did not survive.

“I didn’t blame the government for what was happening. I just didn’t understand what was going on. I asked a professor at my university and all he told me was that I had better watch what I was saying.”

Sun Mu says he wasn’t doing well himself. At school, students were only fed ground corn mixed with plants. At night, he and his classmates would take cabbages from nearby farms.

“If you don’t steal, you don’t survive in North Korea.”

Left with no other option, Sun Mu told his parents that he would travel several hours north to the Tumen River. There he would contact relatives in China and ask them to bring food and money across the border for him to take back home. Sun Mu says he had every intention of coming back.

“I even told one of my friends that when I return that I would buy him lunch.”

But that would never happen. When Sun Mu arrived at the Tumen River, his relatives refused to come to him. Instead they insisted that he cross the river himself and stay with them.

This would be no easy task. Armed guards are stationed along the riverbank with orders to shoot anyone they see trying to escape. Sun Mu staked out the river crossing, hiding in bushes, waiting for the best time to sneak past the soldiers. After 15 days he made his break and stepped onto Chinese soil.

Tens of thousands of North Koreans are thought to have taken the same path as Sun Mu. They come to China in search of food, money and work with the intention to eventually return home. Many do go back, while others crisscross back and forth. China’s northeast is home to an ethnic Korean minority, so the escapees blend in. But Beijing does not recognise them as refugees, instead sees them as economic migrants that must be repatriated. North Koreans in China live in constant fear of detection: if they are sent back home they face months of hard labor in prison camps, torture or public execution.

It took a few months before the reality of it all sank in for Sun Mu. His relatives helped him find work on a tobacco farm. He was earning money and all the while planning to get back to his hometown in time for a national election in the late 1990s. But time was running out. Sun Mu says that if he didn’t get back to vote the authorities would realise he had gone away without permission and some form of punishment would follow. He decided to stay.

“I began to see a lot of things that made me realise something was wrong with my homeland. All I did was cross one river and it was a different world. It confused me. In China people were well fed, while North Koreans were starving. At restaurants people wouldn’t even finish eating. Their leftovers would be given to the pigs. In North Korea, our dream was to eat rice and meat soup, which it was everywhere in China.”

Sun Mu was on the move, he had to be, to avoid capture by the Chinese police. He went from location to location working odd jobs; he picked tree bark for a paper company, he even joined a gang for several months and was paid to rough-up unruly clients in karaoke bars. But on one job loading sacks of flour onto trains, he met a young woman, an ethnic Korean-Chinese, named Jeong.

“At first I didn’t think about marrying her, she was too young. But I thought if someday I ever got to South Korea I would try to help her come there.”

Sun Mu was tired of being on the run. He felt unsafe and craved stability. While in China, many North Koreans receive their first exposure to South Korean culture. Media that is banned back in the North is widely available. The escapees see that the South isn’t the third world hellhole they thought it to be. Sun Mu realised that if he wanted real freedom he would have to make it there.

Sun Mu bought a map of China and plotted his flight. He would have to make it to Southeast Asia, where he could safely reach a South Korean embassy and be granted asylum. At the time of his journey south, most North Koreans relied on a network of safe houses run by Christian missionaries, known as the underground-railroad. But Sun Mu says he along with one other man did it on their own.

They reached Laos, but were arrested by local authorities. The other man, who Sun Mu thought was a refugee like him, turned out to be a Korean-Chinese and was sent back home. After two weeks in jail, Sun Mu was released to Thailand. Finally, he was able to get help and was soon put on a plane bound for Seoul.

“I don’t regret leaving North Korea,” he said. “I still cannot understand how the government could let its people starve to death. But, I feel bad that I didn’t have a plan back then, I didn’t know I was going to end up here. If I had known that, I would have brought my family with me. I would like them to come here, but I know they can’t. Its just too dangerous.”

Stranger in a strange land

Like all North Korean defectors, he was automatically granted South Korean citizenship. He spent three months at a government-run facility where refugees are taught the basics of living in the capitalist world, such as how to use computers, bank machines and cell phones. But all the counseling and preparation could not prepare Sun Mu for his first day at university in Seoul.

“I asked myself why I ever came here,” he said.

After sixty years of division, the two Koreas have gone separate ways. Many North Koreans suffer a culture shock upon arrival. Sun Mu thought the transition into life in the South would be easier, but what he found perplexed him.

He had been accepted into Honggik University, the nation’s top arts school with a very liberal student body. Sun Mu says he wanted to finally finish his degree and make friends while studying. But he could not figure out how to interact with his new classmates.

“I couldn’t understand how these students behaved. I thought they were crazy. Should they see a doctor? We were all speaking Korean, but I couldn’t really understand what they were saying.”

A language barrier is perhaps the most surprising difference that North Koreans discover in their new home. Many English words have seeped into daily usage and many Korean expressions don’t have quite the same meanings here as they do in the North.

“I was really thinking about quitting school.”

But Sun Mu stuck with it. In his coursework, he began to introduce elements of the style of art he was accustomed to. The easily identifiable North Korean propaganda style set off alarm bells within the university’s faculty.

“My professors asked me, why are you painting this kind of stuff? My classmates didn’t know what to think about my art. No one encouraged me. I began to think there was nothing for me here in South Korea.”

But Sun Mu’s fortunes picked up when he met art collector Ryu Byeong-hak, a Korean national who had been living in Germany for the past two decades.

“My first impression of Sun Mu’s paintings was that they were very vivid. I thought you couldn’t find this type of work in South Korea, Germany or anywhere,” Ryu said.

In 2007, Ryu used his contacts in Seoul to get Sun Mu’s work hung up in a gallery. His art would be shown along with photographs from Pyongyang. It was perhaps the first time that pictures of Kim Il Sung and North Korean flags were publically displayed in South Korea. Even though they knew the show would be provocative, neither Sun Mu nor Ryu expected the kind of reaction that followed.

“People called the police and said someone was trying to display real North Korean propaganda. The police showed up on the opening day, but once I explained who I was and what my art is, everything turned out ok,” Sun Mu said.

“Well, it didn’t help that the gallery was located right behind the President’s house,” Ryu added.

Faced with real censorship, Sun Mu had to re-think his initial impressions about South Korean society.

“I thought South Koreans had freedom of expression, but its not completely true. They are still ideologically divided and not as open as I expected when I first arrived.”

Sun Mu continues to have trouble getting his work into galleries here because of the controversy it causes. Likewise, he has been passed over for grants or other endowments given to help support artists.

“Art of course should not be restricted. Censorship of art is in my opinion barbaric. But even when there is official censorship, real art does find a way to exist.”

Despite this resistance to his art, Sun Mu says he is doing just fine. Some of his work has fetched up to $20,000 and he finds many international buyers who are interested in his work. His wife, Jeong, helps the family out with a part time job too.

“Well, all I can say is at least we are not starving,” he says modestly.

Peace through art

“I want North and South Korean children to connect with each other. We can’t deny each other’s existence anymore.”

This past June, Sun Mu came the closest to his hometown in almost a decade. He was on South Korea’s Baengnyeong Island in the Yellow Sea, four hours by boat to Incheon, only 10 minutes to the North Korean coast.

“I felt frustrated, more so than ever before. Why should we live like this? I could see some of the scenery from my hometown through the fog.”

Over the years, Sun Mu’s art has become less about Kim Jong-il and more about symbols of hope. He believes he has a role to play in bringing the two Koreas closer together. There is much mistrust between the two nations, but he wants his art to help lay the groundwork to show that peace is possible.

“The role that art can play is not very obvious. But I still think I can reach out to ordinary people, effect their thinking, I want to change the mindset of these people.”

Sun Mu does not define himself as an artist. He doesn’t have a name for his particular style either. But whatever it is he creates, he wants it to reflect the division of the two countries he both calls home.

“I’ll find a way to bring Korea into a painting. Even if I am painting a zebra, I will put the Korean situation into the piece. I am North Korean, my family is there, the two Koreas are divided and it’s still an international problem. I am still thinking how I can help solve these problems.”

Solving the problems of an entire peninsula is one challenge, trying to explain his past to his own young children is another.

“I tell them your grandmother and your cousins are in North Korea and we have to go there someday.”

But he knows the chances of that actually happening are slim to none.

Sun Mu says his eldest daughter has told some of her friends about her North Korean father and the family there she has yet to meet. The children told her that North Korea is a dangerous place and that if she ever goes there, she will die.

“All I can tell my daughter is that there are people living there.”

Ten years into his new life in South Korea, Sun Mu has started to reflect on the one he gave up. He figures that if he hadn’t made it as a government propagandist, he’d at least be teaching art to upcoming students. And perhaps it’s the stress of living in a fast paced city like Seoul as well as the pressure to support a family that sometimes makes Sun Mu nostalgic.

“What makes me sad is that I will never have that chance to be with my friends, catch fish and make that porridge together again.”

뭐하니展

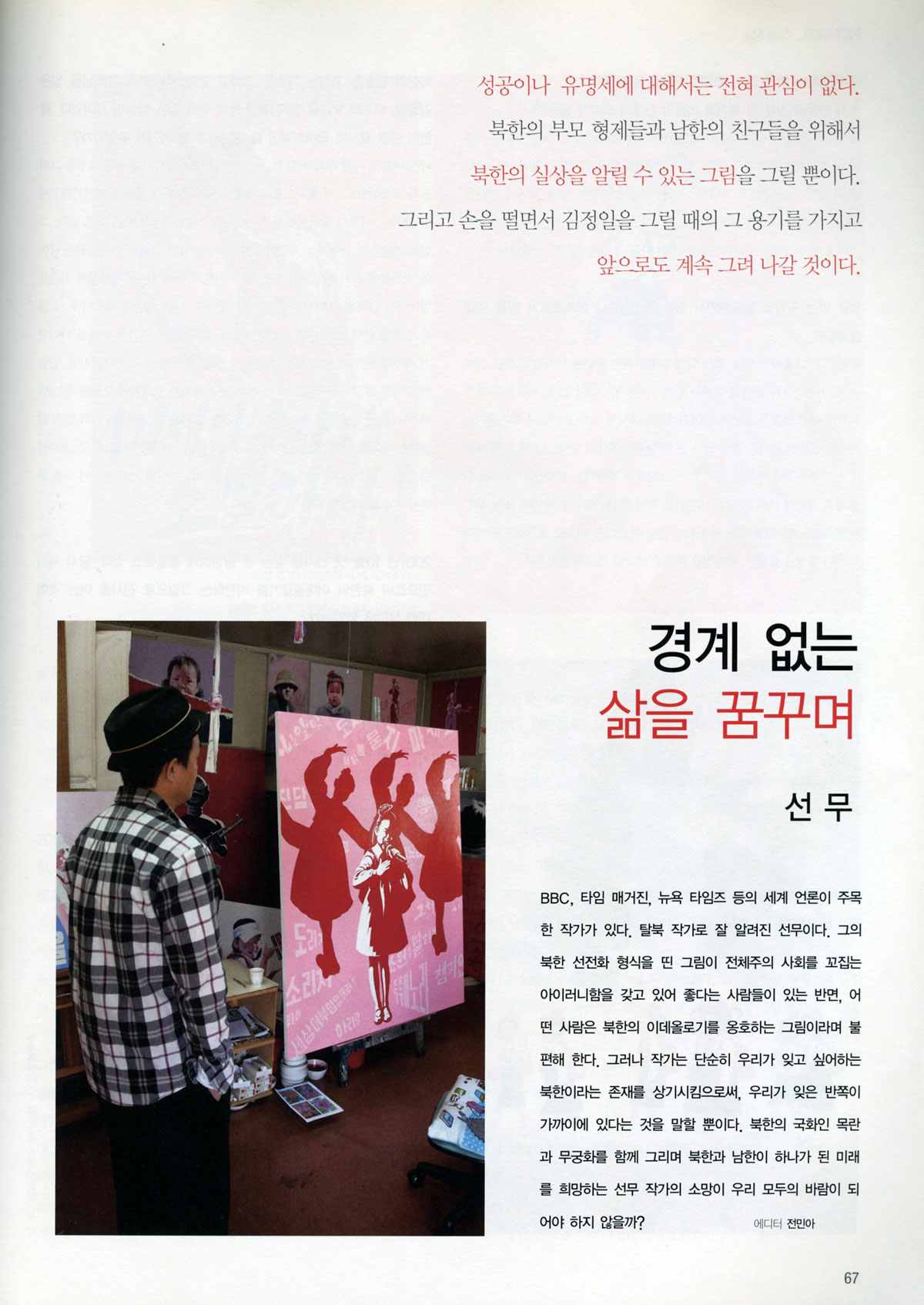

갤러리 담에서는 신년기획초대전으로 선무작가의『뭐하니』전시를 마련하였다. 탈북화가로 잘 알려진 선무작가는 한국에서 선무라는 예명으로 작품활동을 하고 있는데 이번 전시는 열 한번째 개인전이다. 북한에서 탈북하여 김일성 이데올로기에서 벗어나와 작가가 소망하는 유토피아를 그려내고 있다. 태어나면서 청년기까지의 학습된 곳에서 벗어나 환경이 전혀 다른 이곳에서 청년기를 보내면서 겪는 갈등들도 화면 속에 표출하고 있다.「뭐하니」라는 작업에서는 우리를 향해 손가락질을 하면서 지금 우리는 무엇을 하고 있는지 묻고 있다. 또한, 아직 북한에 있는 모친에게도 부칠 수 없는 편지를 그린「편지」를 비롯하여, 언젠가 남북이 함께 갈 날을 소망하며 어린 아이들의 손을 잡고 가는 모습을 그린「우리 함께」, 어린 아이가 오랜 못이 박힌 문을 열어젖히는「문을 열다」는 작품 등 14여 점의 신작이 보여진다. 선무작가는 분단의 선을 비롯하여 우리 사회가 가지고 있는 계층과 계급간의 보이지 않는 갈등들이 없어지기를 희망하며 작업을 하고 있다. 이미 해외에서는 많은 관심을 집중하고 있는 선무작가는 인터내셔널해럴드트리뷴과 뉴욕타임지에 거푸 인상적인 기사와, 영국 BBC, 독일의 ARD, 미국의 Voice of America 등에서 비중있는 다큐멘타리에 등장하였다. ■ 갤러리 담

-

천사의 고민2 An angel's worries2, oil on canvas, 72x61cm, 2012

이사람 선무가 사는 법 ● 1. 지난 4월은 북한이 우주에 쏘아 올린 이상한 물건으로 온통 시끄러웠다. 북한은 인공위성을 실은 우주발사체라 말하고, 미국과 한국언론은 대륙간탄도탄을 위장한 로켓이라 한다. 여기에 가수 신해철이 "북한로켓발사를 경축한다"는 글을 올려 논란을 부추겼다. 여기서 필자는 어느 쪽을 옹호하고 싶지 않다. 이 지면은 날 선 정치적 입장을 밝히는 자리가 아니기 때문이다. 다만, 이 상황에서, 이 상황을 미술적 시선으로 바라보는 작가를 떠올릴 뿐이다. 이름은 선무. 가명이다. 그는 가명을 써야만 하는 사람이다. 한자로는 줄 線. 없을 無. 줄이 없다는 것. 여기서 줄이란, 무언가를 이어주는 것이 아니라, 막는 것, 즉 장애물이다. 결국 그의 이름은 장애물이 없다는 것. 더 정확히 말하면, 이미 놓여있는 장애물을 본인의 의지로 없애겠다는 것이다. 현존하는 장애물을 넘어온 사람이며, 그 장애물 때문에 가명을 써야만 하는 사람인 동시에 장애물을 없애겠다는 의지를 가명에 투사한 사람. 그가 바로 선무다. ● 흥미로운 건, 그가 현존하는 장애물을 없애기 위해 사용하는 도구, 혹은 무기란 고작 두 손, 그리고 손에 잡은 붓과 캔버스, 그리고 붓질을 조율하고, 그의 경험을 기록하고 호명하는 눈 뿐이다. 그렇다. 그는 화가일 뿐이다. 더 흥미로운 것은 이 화가가 보잘것없는 무기로 투쟁하려는 장애물이 실로 어마어마하다는 점이다. 분단. 남북을 가로지른 넘지 못할 줄. 거대한 이념과 이념의 물적 장치인 수많은 살상기계들이 수많은 삶을 짓이겨 찢어 놓은 정치적 실재. 그것이 바로 선무의 장애물이다. 더 정확히 말하면, 이 장애물을 설정하고 유지하는데 공헌한 북한체제와 그 우두머리를 상대로 투쟁하려는 것이다. 손에 붓 하나 꼭 쥔 채 말이다. 그를 처음 만난 건, 2007년 4월인 듯하다. 어느 작은 대안공간의 전시를 준비하고 있을 무렵이었다. 창달린 모자를 깊게 눌러쓰고, 불쑥 옆자리를 차지하고선, 생경한 억양으로, "선생의 생각이 무엇인지 궁금하외다"하고 말을 붙였던 그 사람이다. 모자 챙 아래 살짝 어른거리는 그의 눈빛은 솔직히 나로서도 감당하기 어려웠다. 우린, 서로 독한 시선과 몇 마디 말을 서로 던지고 받은 채 그날을 경험했다. 어딘지 불안한, 그 불안이 과도한 자신감으로 이글거리는 수척한 몰골의 그였다.

그랬던 선무가 다른 모습으로 나타났다. 물론, 그 해 가장 내가 참여했던 전시 가운데 가장 강렬한 인상으로 남은『노순택-선무 2인전, 우린 행복합니다』(호기심에 대한 책임감, 2007)이 비교적 좋은 반응을 얻었고, 같은 해 대안공간 충정각에서 열렸던 1회 개인전이 강렬하게 회자되면서, 서로 잊지 않고 지내긴 했지만, 최근의 성장은 지극히 예상하지 못했던 일이다. 사실, 몇몇 콜렉터들 제외하면, 선무의 그림에 먼저 관심을 보인 것은 해외의 언론이었다. 지난 겨울, 인터네셔널해럴드트리뷴과 타임지에 거푸 인상적인 지면을 차지하더니만, 벌써, 영국 BBC, 독일의 ARD, 미국의 Voice of America 등에서 비중있는 다큐멘타리에 등장했다. 지난 3월에는 호주에서 개최된 북한관련 국제행사에서 북한의 현재를 회화로 증언하는 예술가의 한 명으로 참여했고, 내년엔 미국에서 비중 있는 전시를 앞두고 있다. 그는 이제 그는 그저 정치적 망명가가 아니라, 정치적 문제를 회화라는 방법으로 풀어내는 예술가로서 세상의 시선을 끌고 있다. ● 그는 삶의 경험은 그에게는 정치적 아픔을 동반하는 개인적 아픔임에 틀림없지만, 그는 그 아픔을 붓 하나로 세상의 관심을 끌어내는 매력으로 바꾸는 데 성공하고 있다. 이건 매우 중요한데, 결국 붓 하나 꼭 쥔 그의 손이 거대한 이데올로기적 대립에 기반한 정치적 모순에 맞서는 방법을 비로소 그가 찾아내는데 성공했다는 사실을 의미하기 때문이다. 유일한 방법이자, 가장 효과적인 방법 말이다. 그건, 그림의 매력으로 세상을 휘어잡고, 그의 삶의 아픔, 그 아픔을 초래한 정치적 모순을 세상의 관심 한 복판에 던지는 일이다. 그는 그 길을 찾아낸 것으로 보인다. 그의 그림을 객관적 지평에서 바라보는 평론가의 한 사람으로 이런 평가는 전혀 근거 없는 평가가 아니다. 그와 그의 그림에 관심을 갖는 사람들은 그저 돈 있는 사람들이 아니다. 정치적 이슈를 생산할 수 있는 국제언론, 정치인, 기관의 참여자들이다. 물론, 그가 그의 개인적 아픔과 분단의 모순을 상품화하는 것은 아니다. 그는 단호히 자신의 작품을 아무에게나 판매하지 않겠다고 선언한다. 여기서 중요한 것은 그의 그림이 갖는 시장가치가 아니라, 선무가 사회와 예술이 교차하는 지점을 만들어내는데 성공하고 있다는 점이다.

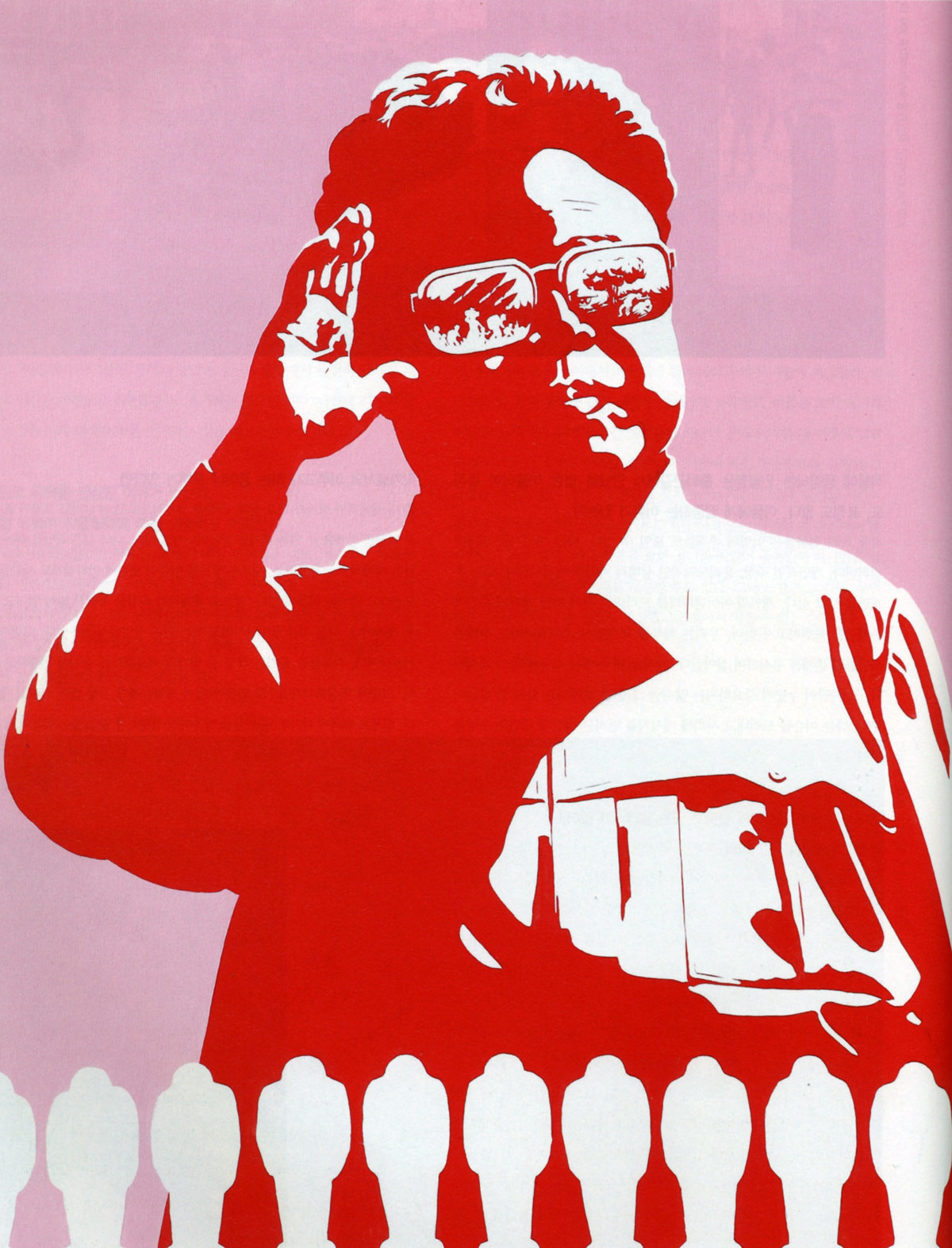

2. 사실, 선무의 그림들을 그리 간단하지 않다. 물론, 간단하지 않은 이유의 가장 큰 요소는 그가 정치적인 그림을 그리기 때문이다. 하지만, 이것만으로는 부족하다. 왜냐하면, 정치적 그림을 그리는 사람들은 여전히 많기 때문이다. 민중미술이 그랬고, 소위 포스트모더니즘의 이상한 형식들이 그러했다. 선무의 정치적 그림은 정치적 그림의 지평에서도 차별적이다. 선무는 대개의 정치적 그림과는 다른 방식으로 자신의 그림을 정치화시킨다. 이점을 독자들에게 납득시키기란 쉬운 일이 아니다. 다만, 이렇게 시작할 수는 있다. 즉, 그는 시각적으로 '겉으로 드러나는 바'와 '의미하는 바'를 대립시킨다는 것이다. 이건, 좀 기호학적으로 복잡한 설명을 동반한다. 시각적으로 드러나는 바를 '기표'(記票, signifier)라 한다면, 의미하는 바는 '기의(記意, signified)'라 할 수 있다. 대개의 정치적 그림은 기표와 기의의 직접성에 근거한다. 예컨대, 80년대 집회나 시위에 등장하는 걸개그림에서 불끈 쥐어진 팔뚝과 주먹(기표)은 있는 그대로 노동자 혹은 농민의 투쟁의 힘을 의미한다. 선무는 이런 기표와 기의의 직접적 관계를 설정하지 않는다. 오히려 선무는 기표와 상반되는 기의를 설정한다. 이점을 좀 더 쉽게 설명하면, 보이는 것 그대로 읽히지 않는다는 것이다. 오히려 선무는 보이는 것과 반대되는 의미를 화면에 부여한다. 이러한 기호학적 화면구사는 선무의 그림을 감상하는 사람들을 난해하게 만든다. ● 예컨대, 선무가, 2007년 대안공간 호기심에 대한 책임감에 김정일의 초상(「조선의 신」, 2007)을 걸었을 때, 가장 먼저, 가장 강렬하게 반응한 것은 주민들이었다. 어찌 김정일의 초상을, 그것도 청와대 지척인 부암동에 버젓이 걸어 놓을 수 있느냐 하는 것이다. 전시기간 내내 주민들의 항의와 신고가 이어졌다. 아마도 출동한 경찰의 수가 전시를 일부러 관람하기 위해 찾아오는 관객 수보다 많은 날도 있었다. 그렇다면, 기표와 기의를 쪼개려는 선무의 시도는 실패한 것이 아닐까? 적어도 주민들은 김정일의 초상을 보고, 적어도 선무가 김정일을 찬양할 의도가 아니라는 사실 정도는 쉽게 알 수 있어야 했다. 선무가 구사하는 기표-기의의 구사가 더 정교하게 나타나는 지점이 이곳이다. 선무는 그의 회화적 가능성의 공간을 기표에만, 혹은 기표와 기의의 자의성에만 두고 있지 않다. 정작 선무는 자신의 의도를 기표로부터 분리된 기의 속에 숨겨 놓는다. 참, 이걸 쉽게 설명하기는 더 어려운 일이다. 하지만, 만약, 이 글의 독자들이 필자가 구사하는 과도한 단순화를 용인해주기만 한다면, 이렇게 말하고 싶다. 즉, 선무는 기표와 기의를 쪼개고, 쪼개진 기의를 다시 쪼갠다. 이걸 비평적인 담화로 표현하면, 글쎄, 시각적 기호의 이중적 분화라 할까? ● 선무는 김정일의 시각적 표현을 최대한 중립화한다. 그건 그저 사실적인 김정일의 얼굴일 뿐이다. 그저 무표정한 사실묘사일 뿐이다. 부암동 주민들은 과연 이렇게 중립화된 김정일의 초상이 무엇을 의미하는지 알 수 없다. 그러나 김정일은 적어도 남한 사회에서 이렇게 그려질 수 없다. 이 땅에서 단순한 사실묘사만으로 중립화되기엔 이 민족에게 저질러진 김정일의 죄가 너무 크기 때문이다. 만약, 그가 북한체제와 그 수괴로서 김정일을 비판할 의도라면, 그는 적어도 김정일에 머리에 괴물같은 뿔이라도 두어 개 그리고, 인민에게 집단구타라도 당하며 나뒹구는 그의 모습이라도 그렸어야 한다. '무찌르자 공산당' 같은 문구라도 넣어서 말이다. 그러나, 선무는 그렇게 하지 않는다. 그렇다면, 선무가 김정일을 미화하고 찬양하기 위해서 그렇게 그렸던 걸까? 물론, 결코 아니다. 그렇다면, 그의 의도는 어떻게 달성되는 걸까? 자신으로 하여금 넘지 못할 선, 사랑하는 가족들을 버리고, 수만 리를 지나 이 생경한 땅에 오도록 강요한 그 사회, 그 체제의 수괴에 대한 정치적 비판의 의도를 어떻게 달성하려는 것일까? 그는 그러한 의도를 철저하게 숨겨놓는다. 그렇다면, 어디에 어떻게 숨겼을까? 힌트는 김정일의 머리 위에 그려진 별이다. 북에서 별은 곧 최고권력자를 의미한다. 그러나 그 별은 가장 뾰족한 모서리를 김정일의 머리 정수리를 겨누고 있다. 별은 이미 선무가 정교하게 틀잡은 캔버스 틀에 의해 무참하게 잘려나가 있다. 북에서 별은 이렇게 그려질 수 없다. 그건 금기에 해당한다. 게다가 선무는 별의 가장 날카로운 끝으로 무방비 상태의 김정일의 머리를 겨누고 있는 것이다. 정치적 비판을 가장 극단적인 방식으로 시각화하고 있는 것이다. 시각적 형태를 통해, 정치적 분노를 가장 극한의 형식으로 밀어 붙이는 것이다.

3. 이런 방식은「세상에 부럼없어라1」(2006)에도 적용된다. 비교적 초기작에 해당하는 이 그림은 더 이상 기쁠 수 없는 북한의 어린이들을 사실적으로 묘사하고 있다. 게다가 선무는 이 그림 아랫부분에 '우리는 행복합니다'라고 쓰고 있지 않은가? 만약, 이 그림을 기표와 기의로 나눈다면, 기표는 희열에 빛나는 북한어린이며, 기의 역시 북한체제가 가져다 주는 행복일 것이다. 그는 무엇을 의미하고 싶었을까? 남한과 북한 사회를 모두 경험해 본 선무가 북한 체제에 향수를 느끼기 시작한 것은 아닐까? 그런 것 같지는 않다. 사실, 만약, 북한체제를 비판하기 위해 헐벗고, 굶주린 북한 어린이를 그렸다면, 그건 화가의 정체성을 갖는다고 보기 어렵다. 현실의 회화적 변환이 성취되었다고 보기 어렵기 때문이다. 선무의 그림을 대할 때의 매력은 이 사람이 정치적 비판이 회화의 가능성의 공간을 따라 우회하는 방식을 추적하는데 있다. 선무가 숨겨놓은 비판을 정확하게 추적하기 위해선 롤랑 바르트가 제공하는 기호학적 개념, 즉 '외연'(外延, denotation)과 '내포'(內包, connotation)을 도입하는 것이 유익할 수 있다. 외연과 내포는 기의, 즉 기호의미를 좀더 세밀하게 관찰하기 위한 도구일 수 있다. ● 외연이란 말 그대로 겉으로 드러나는 명시적 의미를 말한다. 체제와 김정일의 업적을 선전하는 북한의 아이가 기쁨에 겨워 밝게 웃고 있다면, 그 웃음+표정의 외연은 드러나는 것처럼 김정일의 위대함과 북한체제의 우월함이다. 반면, 내포란, 좀더 깊숙이 '숨겨진 의미'를 의미한다. 선무의 화가로서의 자질은 기호의 의미의 지평에서, 외연과 내포를 정확하게 대립되는 방식으로 구사할 수 있는 능력이다. 북한 어린이가 보여주는 기쁨과 희열의 외연은 김정일과 북한에 대한 극도의 찬양이지만, 내포는 그 찬양이 너무나도 극단적이라는 것, 그래서 비현실적이라는 것이다. 현실을 사실적으로 묘사하면서도, 현실의 가장 비현실적인 속성을 드러내는 것이다. 눈에 보이는 현실이, 현실임에도 불구하고 결코 현실 속에서 가능하지 않음에 대한 일종의 은유적 고발이랄까? ● 소녀는 또래의 다른 소녀들이 도저히 그럴 수 없을 만큼 기뻐하고 있다. 이 기쁨이 과연 진실일까? 도저히 진실일 수 없는 진실, 그것은 혹여 가장된 위장일 가능성이 높다. 현실을 가상으로 위장하는 것이 아니라, 가상을 현실화하는 위장이다. 현실을 가상으로 재구성하는 것은 몇 마디의 말이면 충분하지만, 가상을 현실화하는 위장은 집단, 혹은 사회전체의 수준에서 위장을 강요하고 강화하는 강고한 시스템이 필요하다. 정작 기쁨에 겨워하는 북한 어린이를 그렸을 때, 선무가 숨겨놓은 내포는 그런 기쁨이 현실에서 가능하지 않은 위장이며, 이 위장을 현실 속에서 가능케 하는 북한사회 체제가 갖는 불가해한 폭력성이라는 것이다. 결국 동일한 기표를 통해 상반된 외연과 내포를 서로 대립적으로 구성해 낼 수 있는 능력, 그것이 선무가 보여주는 회화의 세계라는 것이다. 이런 방식의 기호학적 화면구성은 선무가 보여주는 그림들을 전반적으로 관통하고 있다. 사실 그는 사실적 묘사에 충실한 리얼리즘 화가이지만, 더 본질적으로는 의미를 다루는 정교한 기호학자에 가깝다고 볼 수 있다. 재미있는 것은 그가 다루고 처치하는 의미가 결국 사실을 재료로 수행되고 있다는 것이다. 사실을 통해 의미의 세계를 시각화하는 사람. 그가 바로 선무다.

4. 지난해 인사동 쌈지갤러리에서 열렸던 두 번째 개인전『세상에 부럼없어라』는 또 다른 세계를 보여준다. 전작들은 주로 선무가 북한에서 배웠던 선전화풍의 이미지 조직방식에 기초해 있다. 사실적인 묘사, 거대한 캔버스 위에서 붉은 색과 푸른 색 중심의 강렬한 색과 구도를 통해, 두만강을 건널 때의 분노와 절망, 불안을 그렸다면, 두 번째 개인전에선 드디어, 남한에서 익힌 소위 서구적 현대미술의 영향이 드러나기 시작했다. 가장 중요한 변화는 무엇보다 유머코드가 등장하기 시작했다는 것이다. ● 유머란 삶의 질곡을 뛰어 넘어 공동체를 형성하는 감성적 기반이기도 하지만, 가장 효과적인 약자들의 무기이기도 하다. 유머란, 작은 웃음으로 굳고 강건한 덩치의 적에게 무시할 수 없는 균열을 내는 예술적 무기라는 것이다. 나이키 운동복과 아디다스 신발을 신고서 뒤뚱거리며 우스꽝스운 표정을 짓는 김정일. 이건 단순한 불경이나 조롱이 아니다. 선무는 김정일의 존재와 권위를 우스꽝스럽게 희화화시킨다. 그는 그저 광대처럼 경망스럽게, 익살스럽게 웃고 있다. 물론, 선무가 구사하는 유머는 폐부를 찌르는 양가적인 의도를 가지고 있다. 비판적 함의는 개혁 개방을 거부하면서도, 그 자신은 세계적인 상품으로 사치를 즐기는 김정일을 희화화하는 것이다. 이 작품은 그러나 비판에만 그치지 않는다. 그림 속의 김정일은 행복해 보인다. 이 모습은 선무의 그림에서 언제나 굳은 표정을 짓던 독재자가 아니다. 독재자는 과잉 집중된 권력의 중심이면서 동시에 바로 그 권력 때문에 언제나 그 누구보다 불안한 사람이기도 하다. 권력이 주는 거만함과 불안함은 선무의 그림 속에서 김정일의 무표정한 얼굴로 나타났다. 그런데 서양의 품질 좋은 상품들로 치장한 김정일의 표정에는 그러한 거만과 불안이 존재하지 않는다. 오히려 선무의 그림 속에서 김정일은 행복해 보인다. 이 행복한 표정이 던지는 정치적 함의는 무엇일까? 선무는 그림 속 김정일에게 어떤 의미를 부여한 걸까? 어쩌면, 선무는 개혁 개방이 인민을 위하는 길일 뿐 아니라, 김정일 자신에게도 행복을 가져다 주는 길이라고 말하고 싶었던 것은 아닐까?

그것이 비판이건, 정치적 요구이건, 선무는 자신의 의도를 유머코드를 통해, 회화적 의미의 지평에서 효과적인 방식으로 전달하고 있다. 정치적인 비판이라는 무거운 주제를 가벼운 외양으로 던져 놓은 이 작품의 재미는 이후 다양한 매체들의 관심을 끌었고, 세계에 전달되었다. 이 밖에 특정한 오브제를 형태적으로 반복팝아트의 형식 또한 관찰된다. 마릴린 먼로, 코카콜라, 브릴로 박스와 같은 대중문화의 오브제들을 무한히 반복함으로써 화면을 채워나갔던 엔디워홀의 경우처럼, 선무 역시 그가 집착하고 있던 북한 어린이의 모습을 질서정연하게 늘어놓고 있다는 것이다. 남한 사회에서의 생경한 자본주의적 경험들을 북한에서의 경험과 병치하는 방식들도 눈에 띈다. 특히, 전라, 혹은 반라의 여성누드와 인공기를 병치하는 방식은 보다 강렬한 비판의 메시지를 전달한다. 그것은 북한체제에 대한 모독적인 불경인 동시에 좀 더 인간의 자연스런 욕망을 존중하는 사회에 대한 갈망일 수 있다. 선무의 회화적 방법이 진화하는 과정은 미술이 그저 미술일 수만은 없음을 보여준다. 미술은 투쟁이다. 미술은 과거의 미술에 대한, 미래의 미술을 위한 투쟁일 뿐 아니라, 미술이 사회와 교차하는 지점에서 나름의 변화와 변혁을 요구하는 정치적 투쟁이기도 하다. 선무는 이 정치적 투쟁을 미학적인 방식으로 변환할 뿐 아니라, 그 역의 변환 역시 시도하고 있다. 즉 미학적인 방식으로 정치적 투쟁을 실천하는 것이다. 이 미학적이자 정치적 투쟁의 거대한 지형은 정작 선무라는 한 작가의 손에 잡힌 작은 붓 한 자루에 의해 지탱되고 있는 것이다. 물론, 선무가 이 상황에서 할 수 있는 일은 아무것도 없다. 그가 경색된 남북관계를 복원하는 데 어떤 정치적 역할을 수행할 수 있는 것은 아니다. 다만, 그는 정작 이 시대, 이 상황에서 필요한 것이 무엇인가를 가장 새로운 방식으로 풀어내고 있다. 그의 그림 속에서 남북은 그저 피 흘리며 싸우는 대립적 투쟁의 상대가 아니라는 것이다. 그의 그림에서 그려지는 모든 상황들은 언젠가는 제자리로 돌아와야 할 것들이다. 그의 그림이 현실과 조응하며, 세상을 바꾸고, 세상과 함께 바뀌어 가는 모습을 지켜보는 것은 동시대 미술장에 참여하는 관객에겐 일종의 행운이라 할 수 있다. ■ 김동일

All That is Banned is Desired, 2012: 'North Korea'

This was Session 9 on Day 2 of the conference 'All that is banned is desired' which was held in Oslo, Norway, in October 2012.

Speaker: Sun Mu (North Korea)

Moderator: Sigrun Slapgard, Writer, Foreign Correspondent and Board Member of Fritt Ord

"Every single day is a challenge"

Interview with Sun Mu, Visual Artist from North Korea (now living in South Korea), who participated in the first world conference on artistic freedom of expression, 'All that is banned is desired', held in Oslo on 25-26 October 2012.

좌우지간 左右之間 in any case

이번 전시에서 선무는 새롭게 설치작업을 시도한다. 2005년 이후 지금까지 선무의 작업들은 작가 자신의 과거를 돌아보는 작업들이었다. 때로 떠나온 곳에 대한 그리운 회상이었고, 때론 뼈아픈 질문이었다. 자신의 아픈 과거와 대면하고 그것을 들여다보는 일이 결코 쉬운 일만은 아니었을 것이다. 다른 이념의 사회, 다른 미술의 언어와 태도들 속에서, 그가 처음 수행한 일은, 자기 자신을 돌아보는 일이었다. 지난 수년간 그는 그 과정을 꿋꿋이 지속해 왔다. '좌우지간' 말이다. 그 그림 중 하나에 대해 나는 이런 질문을 했었다. "이 그림은 북한 사회를 비판하고 있는 것입니까." 돌아온 답은 이랬다. "아니요. 내 어린 시절을 회상하는 것입니다." 어쩐지 부끄러웠다. 나도 모르는 사이, 남과 북, 마주한 두 사회의 대결구도로, 누가 옳은지 겨루는 시선으로 그의 작업을 바라본 것은 아니었을까. 그것은 단순히 무지에서 비롯한 오해라기보다는 편협하고 조급하게 다그쳐 묻는 추문(推問)에 가까왔으리라. 그는 오히려 덤덤했다. 그런 엇갈림들이 얼마나 많이 있었겠는가.

그간 그의 작업에는 주체미술의 조형적 특성과 내용들이 유지되어 왔다. 그러나 이 그림들은 그가 과거에 주체미술의 안에서 그려낸 그림으로 끊임없이 돌아가고 있지만, 결코 같은 그림일 수는 없다. 과거를 돌아보고 그 곳으로 되돌아간다 해도, 그는 여전히 과거의 '자기의 밖에 있으며' (exsistere) 자신과 거리를 두게 되기 때문이다. 말할 필요도 없는 당연한 얘기같아 보이지만, '찬양이냐, 비판이냐'라는 식의 다그침을 비롯한 여러 오해들은 사실, 이러한 당연한 사실을 심사숙고 해보면 좁혀질 수 있는 엇갈림들이 아니었을까 싶다. 현재의 그는 과거의 자기 자신을 부정하면서도 동시에 끊임없이 그 둘의 동일성을 추구할 수 밖에 없는 것이다. 그것은 어느 누구에게나 해당되는 자기 성찰의 본질적 진리이다. 그렇기 때문에 그의 여기 있음은 '아직 아님', '아직 있지 않음'의 미완의 형태로 반성적 지평 위에 존립한다. 그의 작업은 이러한 반성적 지평 위에 소환되고, 부정되고, 해체되고, 새롭게 통일되기를 반복해왔다.

이번 선무의 작업에서는 그간의 길었던 자신과의 대화가 세계와의 대화로 넘어가는 모습을 발견하게 된다. 설치계획을 보면, 이번 작업에서 그는 현재 자기 앞에 펼쳐진 세계의 벽과 모순에 대한 직설적이고 과감한 어법을 구사하고 있다. 그가 과거를 되돌아볼 때, 과거는 자신을 넘어가 현재로, 미래로 이어질 것을 요구한다. 고통스런 회상과 성찰은 과정일 뿐 결코 자신을 절대화할 수 없다. 그는 고개를 들어 지금 여기를 향해 말하기 시작한다. 고통이여 '좌우지간' 사라져라! ● 눈 앞의 현실을 향해 발언할 때 자기 앞에 서있는 수많은 '너'들과 정면으로 마주하게 된다. 동시에, 나 역시 그 수많은 '너' 중의 하나라는 것을 인정하지 않을 수 없다. 서로 다른 이념과 다른 고통들, 다른 삶의 방식과 다른 미술의 언어들 사이에서, 너와의 적극적인 대면을 통해서만 얻을 수 있는 자신의 개별적 주체성을 고민해야만 한다. 이번 전시에서 가장 절실한 것을 품고서 자기 현재의 지평을 열고자 세상에 부딪히는 작가의 진실과 용기를 만날 수 있을 것이라 기대한다. 그 어조와 수사는 시간과 함께 변화하고 자기 발전 과정을 겪게 되겠지만, 이 열정은 쉽게 잊혀지지 않을 것이다. ■ 藝術基地 땅굴

Delving into North Korea's mystical cult of personality

very night, North Korea's news bulletin begins with a song about the mythical qualities of the country's leader Kim Jong-il and the mountain where he is said to have been born.

North Koreans are used to the hyperbole of their state media, with a constant stream of stories about Kim Jong-il's economic guidance and benevolent care.

And since the death of the Dear Leader on 17 December, the media have focused their attention on a series of strange, natural phenomena being reported across the country - a giant lake of ice cracking in half, a red glow covering the mountain where their leader was born and, most recently, magpies gathering by the dozens in a single tree, in grief, according to one party official.

"We can't dismiss it as just a natural phenomenon," he told state television. "It shows that not only the people of the world, but the animals too, cannot forget our Dear Leader."

This is hardly surprising, perhaps, when his image - and that of his father Kim Il-sung - appears everywhere in billboards, buildings, television reports and every office wall.

Along with the army, North Korea's media apparatus is perhaps the institution most responsible for keeping its leaders in power.

It built powerful personality cults around both Kim Jong-il and his father and is now beginning to do the same with his son and successor, Kim Jong-un.

It is a myth-making factory that, for most of its audience, is their only source of news.

'Flowery language'

Brian Myers, professor of International Relations at Dongseo University in South Korea, has studied the archives of North Korean media reports closely.

He says this kind of imagery from the natural world has been seen before in other political systems.

"There is the belief, which was common also in imperial Japan and Nazi Germany, that the actual physical territory occupied by the nation reflects the attributes of the race itself," he said.

"And this kind of flowery language that we've seen in the past few days, of ice cracking and cranes being seen in the sky, does reflect a uniquely North Korea understanding of a connection between the territory and the race."

And in the case of Kim Jong-il, he said, the media have spent years stirring up complex feelings in the minds of people.

"Kim Jong-il's official image in the propaganda was always a man with no time for himself, and a large part of the propaganda was aimed at making the public feel guilty about the overwork that he was subjecting himself to, Mr Myers said.

"And I think these feelings of guilt are a part of the whole mourning ceremony now."

'Taboo' art

Sunmu, a former North Korean state artist now living here in Seoul, used to be part of that propaganda machine. He remembers working under North Korea's first leader, Kim Il-sung.

The media machine was so tightly-controlled, he said, that only a handful of people were allowed to draw the leader himself.

"All the directives of what the picture should be about, and how it should be drawn came down from higher up and all I needed to do was follow them," Sunmu said.

"I wanted to draw Kim Il-sung himself but only a few designated artists were allowed to. So I would lock myself into a room to draw Kim Il-sung and then burn it. Even my parents could not know I'd done that."

Sunmu said he would have ended up in a political prison camp "or maybe even executed" if anyone had found out about his drawing.

But the urge to draw him was so strong because it was "taboo" for ordinary artists to do so.

This time around, he said, the North Korean media appear to be focusing more on the "Great Successor", Kim Jong-il's youngest son and the country's presumed new leader.

Kim Jong-un is a man in his 20s who already looks strikingly like his grandfather, who is North Korea's eternal president.

Untried and untested, he will perhaps depend even more on the power of his lineage, and the personality cult created by his country's unique cultural machine.

via BBC