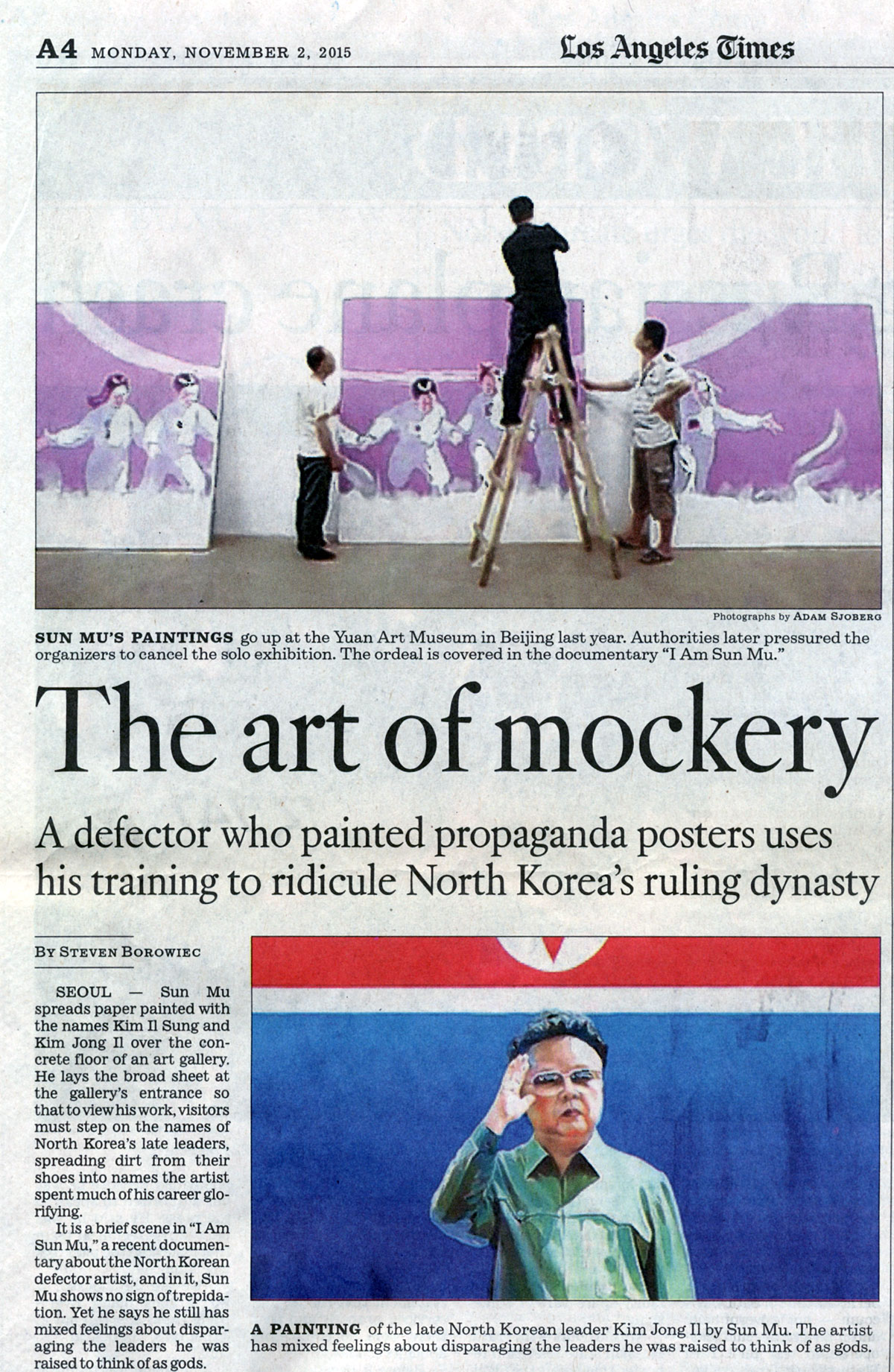

Sun Mu : From propaganda to protest, one artist’s creative rebellion against the Kim regime

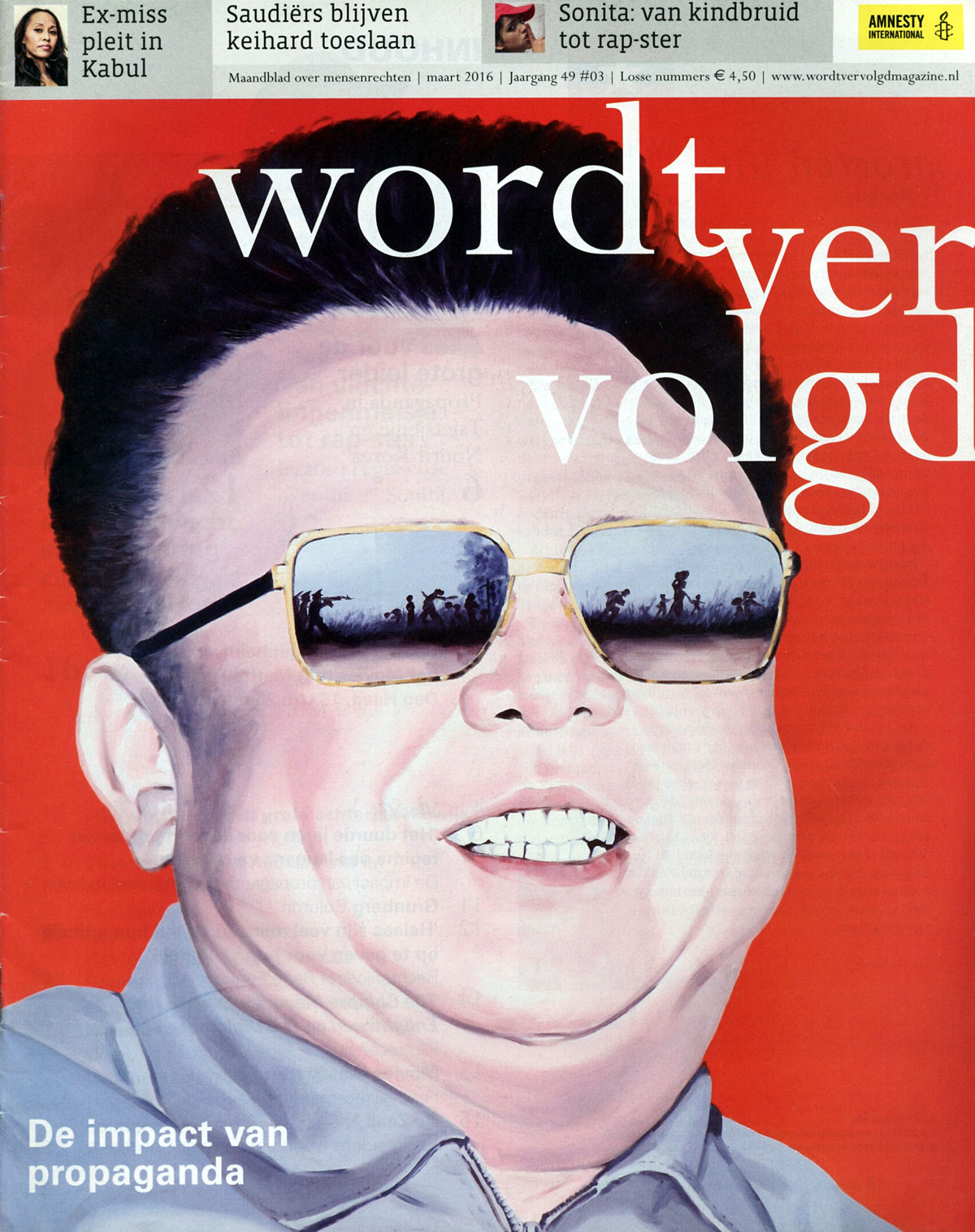

At first glance, it’s easy to mistake the art of Sun Mu for North Korean propaganda. In one piece, Kim Jong-il is rendered in bright red, his face twisted into a toothy, grotesque smile. But upon closer inspection, Kim’s glasses reflect an execution scene—a military man’s gun raised in the direction of a female worker in the fields—and in his hand, the late dictator menacingly wields a knife.

The resemblance to the military posters that paper North Korean streets is no accident—trained as a propaganda artist for the Kim regime, Sun Mu used to make those posters. He escaped in 1998, fleeing a devastating famine that killed an estimated 330,000 people, seeking refuge in South Korea. There, the artist began painting once again, except now using his talents to forge blistering critiques of the regime for which he once worked.

His artwork evokes the painting and composition styles of self-glorifying regime art—which often represent leaders as god-like figures exercising extreme military might—but it depicts scenes of servile subjugation and absurd portraits of North Korean despots instead. Symbols of capitalist America pervade his portrayals of life in North Korea—a rosy-cheeked baby sips a Coca-Cola, a schoolgirl clutches a Starbucks cup, Mickey Mouse ears crown the head of Kim Jong-un—demonstrating the complicated geopolitics that govern the ideological landscape of North Korea. The subjects illustrated in his posters wear smiles stretched so widely they communicate exhaustion rather than joy. “To me, the most important thing about work is people,” Sun Mu says . “I always...try to figure out what it means [to live] life as a human.”

His artwork evokes the painting and composition styles of self-glorifying regime art—which often represent leaders as god-like figures exercising extreme military might—but it depicts scenes of servile subjugation and absurd portraits of North Korean despots instead. Symbols of capitalist America pervade his portrayals of life in North Korea—a rosy-cheeked baby sips a Coca-Cola, a schoolgirl clutches a Starbucks cup, Mickey Mouse ears crown the head of Kim Jong-un—demonstrating the complicated geopolitics that govern the ideological landscape of North Korea. The subjects illustrated in his posters wear smiles stretched so widely they communicate exhaustion rather than joy. “To me, the most important thing about work is people,” Sun Mu says . “I always...try to figure out what it means [to live] life as a human.”

Even outside North Korea, the threat of retaliation by the regime is very real and Sun Mu still encounters resistance to his art. In Seoul, authorities mistook his posters for communist propaganda and questioned him about the meaning of his work. In 2014, a Beijing exhibition was suspended for unspecified reasons and his identity nearly exposed. He still has family in the country, which is why he uses a pseudonym and refuses to be photographed. And although he was granted South Korean citizenship, he says the North Korean government has attempted to kidnap and silence him. But Sun Mu hasn’t been deterred. I Am Sun Mu, a documentary chronicling his life and work, debuted this past October, and he is looking forward to more exhibitions of his work in Beijing and Europe this year. “I want to let the world know that people like me exist,” Sun Mu wrote in a poem that accompanied his 2014 Beijing show. Now, they do.

by Tasbeeh Herwees Via Good

De kunstenaar zonder gezicht

Sun Mu De Noord-Koreaanse kunstenaar Sun Mu vluchtte eind jaren negentig naar China. Nu is er een film over zijn kunst.

De familie van de gevluchte Noord-Koreaanse kunstenaar Sun Mu loopt gevaar als zijn identiteit bekend wordt. Dus als hij zich in het openbaar vertoont, moet dat altijd onherkenbaar. Van tevoren is afgesproken dat Sun Mu (niet zijn echte naam) op de foto kan, mits gemaskerd en met een hoed op. Maar als de fotograaf begint, wil hij toch nog onherkenbaarder in beeld. Hij pakt het tijdschrift Wordt Vervolgd met op de cover een door hemzelf gemaakt portret van de voormalige Noord-Koreaanse premier Kim Jong-il en houdt dat voor zijn mond. De assistent van de fotograaf heeft een idee: wat als hij de mond van de Grote Leider voor zijn mond houdt? Sun Mu kan deze vinding wel waarderen: „Good job.”

Sun Mu is niet zonder reden zo wantrouwend tijdens zijn eerste bezoek aan Europa. Hoewel hij over de hele wereld exposeert, komt hij weinig in de openbaarheid. In de film I am Sun Mu (Adam Sjöberg) die vanavond op het filmfestival Movies that Matter vertoond wordt, is te zien hoe gevaarlijk dat voor hem is. De film volgt hem tijdens de voorbereiding van zijn eerste expositie in Beijing in 2014. Een museum heeft het aangedurfd zijn werk, dat kritiek uit op het regime in Noord-Korea, te vertonen. Om de schilderijen te kunnen zien, moeten bezoekers op een kleed stappen met daarop de namen van Kim Jong-il en Kim Jong-un.

Binnen een paar uur na de opening staat de Chinese politie op de stoep, vergezeld van vermoedelijk de Noord-Koreaanse geheime dienst. De tentoonstelling moet dicht, het werk wordt in beslag genomen en de museumdirecteur wordt uren ondervraagd. Sun Mu en zijn gezin nemen direct het vliegtuig naar Seoul. Naar China kan hij nu nooit terug. Contact met de museumdirecteur is er niet meer. „Er moet iets gebeurd zijn”, zegt Sun Mu. „Misschien hebben ze enorme druk op hem uitgeoefend.”

Sun Mu, die in Noord-Korea op een kunstacademie zat en tijdens zijn militaire dienst ook kortstondig propaganda moest tekenen voor het regime, stak eind jaren negentig de grens over met China. De reden: ‘de vreselijke honger’. „Mijn plan was na een paar maanden weer terug te gaan, maar ik realiseerde me al snel dat dit gevaar zou opleveren voor mijn familie.”

„Ik ontdekte dat wie ik dacht dat ik was, gebaseerd was op een leugen

En dus woont hij nu Seoul, waar hij bekendstaat als de ‘kunstenaar zonder gezicht’ en waar hij zich wekelijks moet melden bij de Zuid-Koreaanse politie. „De Zuid-Koreaanse regering houdt Noord-Koreanen nauwlettend in het oog. Officieel ‘uit bescherming’, maar ook om zeker te weten of we geen spionnen zijn.”

Sommige vluchtelingen uit Noord-Korea kunnen maar moeilijk aarden in Zuid-Korea. Ze vinden de (keuze)vrijheid overweldigend. Hoe was de overgang voor Sun Mu? „Het moeilijkste vond ik te ontdekken dat alles waar ik in geloofde, nep was. Dat wie ik dacht dat ik was, gebaseerd was op een leugen. Ik kan daar nog steeds niet te veel aan denken, het is te pijnlijk.”

Waar het werk van andere Noord-Koreaanse vluchtelingen soms depressief, donker en zwaar kan ogen, is de kleurrijke kunst van Sun Mu opvallend licht en humorvol. Op het schilderij Take some medicine ligt Kim Jong-il ziek in bed, terwijl een meisje hem een flesje Coca Cola aanbiedt. Hij lijkt daarmee niet alleen commentaar te willen leveren op het regime in Noord-Korea, maar ook op hoe in het Westen naar Noord-Korea wordt gekeken. „Het is een te zwart-wit beeld. Iedereen denkt bij de beelden van zingende Noord-Koreaanse kinderen dat alles onecht is. Ja, er zit een dictator, maar er zijn veel Noord-Koreanen die geloven dat ze gelukkig zijn.”

Het is waarom in Sun Mu’s werk geen rancune zit, maar liefde en hoop: van een oud stuk prikkeldraad van de gedemilitariseerde zone maakt hij takken van rozen die hij in een vaas zet. „Ik kijk liever niet naar het heden, maar naar de toekomst. De Noord- en Zuid-Koreaanse regering moeten niet verharden, maar zachter worden. Laat er mildheid zijn.”

Via NRC

Propagandakunst als verzetsdaad

De Noord-Koreaan Sun Mu (44) maakte ooit propagandakunst in opdracht van het regime. Na zijn vlucht draait de kunstenaar de rollen om en bestrijdt hij de dictatuur van Kim Jong-un met haar eigen middelen.

De schilderijen van de Noord-Koreaanse Sun Mu kunnen op het eerste gezicht doorgaan voor communistische propaganda. In helder blauw en knallend rood schildert hij vrolijke gezichten. Kinderen met partijsjaaltjes, oud-leider Kim Jong-il lachend met een zonnebril op. Een lief meisje met een brief in haar handen. Alleen zijn de beelden juist anti-communistisch en gericht tegen het regime: in de weerspiegeling van de zonnebril van Kim Jong-il zijn soldaten en hardwerkende landarbeiders te zien, het meisje drinkt cola en de brief zal nooit verstuurd worden.

Sun Mu (uit veiligheidsoverwegingen niet zijn echte naam) is in Nederland voor het 'Movies that Matter'-filmfestival, waar de documentaire 'I Am Sun Mu' wordt getoond. De film laat zien hoe de kunstenaar zich - zonder een moment met zijn gezicht in beeld te komen - voorbereidt op een grote solotentoonstelling in Peking. In de documentaire is hij alleen van achteren te zien, in het donker met een zonnebril op. Vluchtelingen lopen ook buiten Noord-Korea groot gevaar. Tijdens een opening van een expositie van Mu in Berlijn draagt hij een doek over zijn gezicht, alleen zijn ogen zijn te zien. Hij doet er alles om te voorkomen dat hij herkenbaar in beeld komt. In de lobby van een hotel in Den Haag hoeft hij zijn gezicht niet te bedekken, maar op de foto wil hij absoluut niet: "Dan zou ik mijn familie in gevaar brengen."

Sun Mu is een van de weinige Noord-Koreaanse kunstenaars die zijn werk met de rest van de wereld kan delen. Op een haast satirische manier bekritiseert hij het dictatoriale regime.

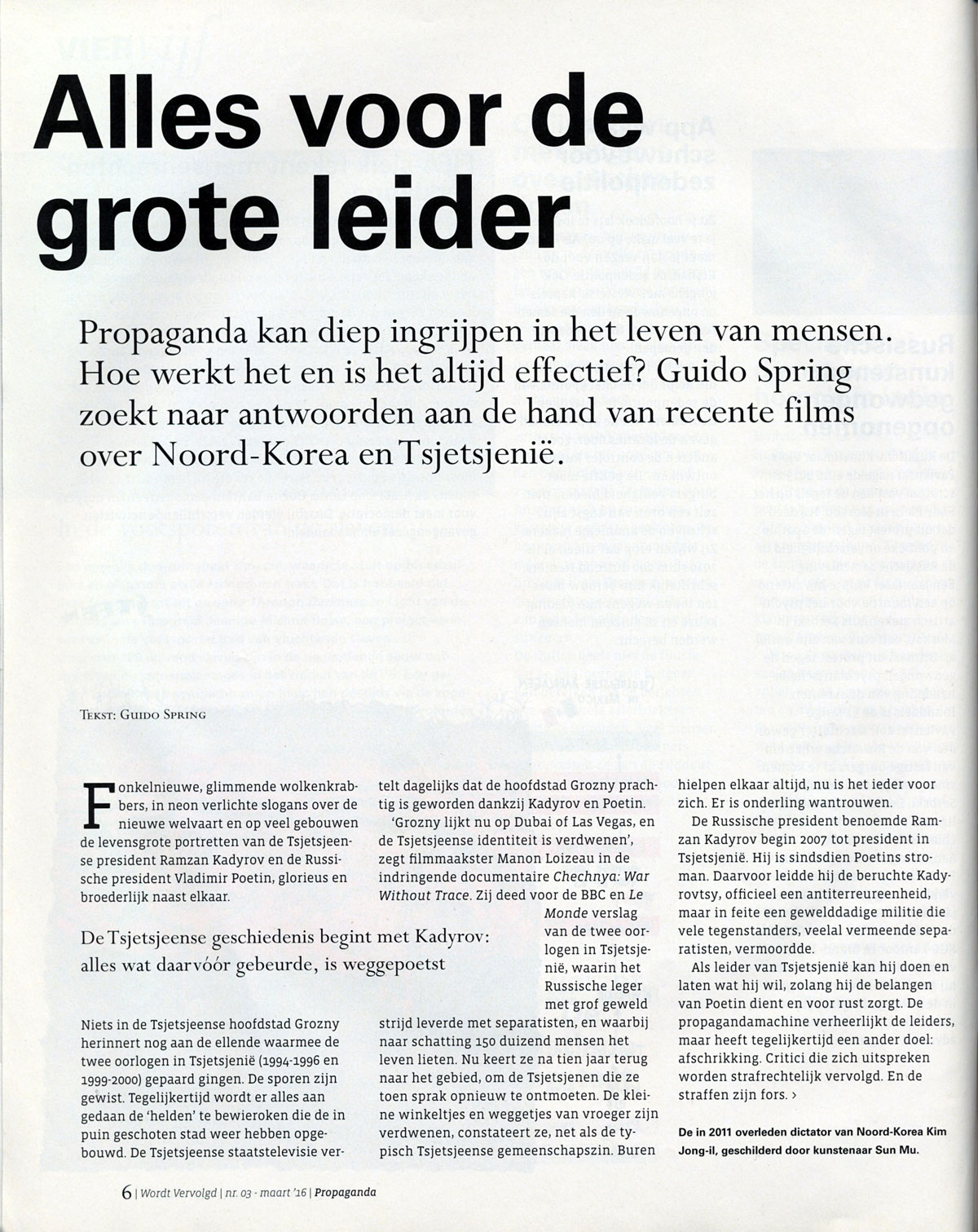

Hij schilderde bijvoorbeeld een grijnzende, dikke Kim Jong-il in een Adidas-trainingspak. En zijn zoon, de huidige leider van Noord-Korea, wordt afgebeeld omringd door allerlei Disneyfiguren.

Tijdens zijn militaire dienst in Noord-Korea had Sun Mu de opdracht om propaganda-schilderijen te maken. Hij maakte bijvoorbeeld afbeeldingen waarop Noord-Koreaanse soldaten de kelen doorsneden van Amerikaanse soldaten. Welgeteld één keer tekende Sun Mu zijn leider Kim Jong- il. Dat was eigenlijk ten strengste verboden, slechts een paar kunstenaars was het recht voorbehouden om de 'grote leider' af te beelden. Sun Mu had zijn deur op slot gedraaid. Hij was doodsbang dat de mannen van Kim Jong-il hem zouden pakken en neersteken. Zijn tekening was nog niet af of hij had hem al in brand gestoken.

Hij vertelt dat hij geen andere kunstenaars als voorbeeld heeft, zijn inspiratie vindt hij bij de dictators van Noord Korea: "Dat klinkt misschien gek. Maar mijn leven stond jarenlang in het teken van Kim Jong-un en Kim Jong-il. Ik heb keihard voor ze gewerkt en was zelfs bereid om voor ze te sterven."

Door de ernstige hongersnood die Noord-Korea eind jaren negentig in zijn greep hield, voelde Sun Mu zich in 1998 gedwongen om te vertrekken. Hij bereikte China zwemmend over de rivier de Tumen. Via Laos en Thailand kwam hij uiteindelijk in 2002 in Zuid-Korea terecht. Het regime liet hem alleen niet los. "In Noord-Korea leerde ik dat het kapitalisme er van de buitenkant mooi uitziet: met felle, knipperende lichtjes en glitters. Maar dat het systeem van binnen verrot is." De ommekeer kwam langzaam: "Op een gegeven moment begon ik steeds duidelijker te zien dat ik al die tijd bedrogen was. Ik kon als een buitenstaander naar mijn eigen land kijken. "

Vloerkleed met teksten

Voor zijn tentoonstelling in Peking (2014) maakte hij een vloerkleed met lyrische teksten over de Noord-Koreaanse leiders en zijn vaderland. Iedereen die de tentoonstelling zou bezoeken, dus ook de medewerkers van de Noord-Koreaanse ambassade, zou bij het betreden van de ruimte met zijn voeten over dat kleed moeten stappen. Dat was althans zijn idee, maar dat moment is nooit gekomen, zucht hij.

Zijn tentoonstelling in Peking werd alleen op de dag van de opening - waar hij zelf sowieso al niet bij aanwezig kon zijn - gesloten door de Chinese autoriteiten. Hij besefte eens te meer dat hij nog steeds in gevaar is: halsoverkop moest hij met zijn vrouw en twee dochters het land verlaten. Terug naar Zuid-Korea waar hij inmiddels bekend staat als de 'kunstenaar zonder gezicht'.

Zijn ouders zijn nog altijd in Noord-Korea: "Hoe is het mogelijk dat een heel volk al die jaren bedrogen wordt?" Zijn familie en vrienden in Noord-Korea hebben zijn kunstwerken waar hij nu furore mee maakt nooit gezien. "Ik kan mijn geluk niet met hen delen." Hij is even stil: "Toch weet ik zeker dat als mijn ouders en andere Noord-Koreanen mijn schilderijen zouden zien, dat ze - ondanks de jarenlange hersenspoeling - het zouden begrijpen." Het is zijn droom om zijn werken ooit in Pyonyang te exposeren. "Ik heb hoop: Kim Jong-un ziet er niet gezond uit, hij zal denk ik niet lang leven."

De documentaire 'I am Sun Mu' (regisseur: Adam Sjöberg) is vanavond om 21.15 nog te zien tijdens het Movies that Matter festival in Den Haag.

Via Trouw

Sun Mu at the Movies that Matter Festival 2016

Defector Artists Dream of a Borderless Korea

TALES OF TWO KOREAS

Defector Artists Dream of a Borderless Korea

More than 28,000 North Korean defectors have settled in the South after fleeing their home country in a quest for freedom or escape from hunger. Among them are not a few people who had studied art or worked as artists in the North. As the conflict between the two Koreas shows no signs of abating, they express through their work their personal memories of their hometowns and yearning for reunification.

“Take Off Your Clothes and Play” by Sun Mu, 2015, oil on canvas, 130cm x 190cm

At first glance, many of the works by defector artists from North Korea express overt propaganda messages, though the implications are never the same as would be the case if they were back in the North. In fact, Sun Mu, a painter in his mid-forties, had actually experienced the consequences of such a misinterpretation of his art. In 2007, he held the first exhibition of his artworks in South Korea at a gallery in Jongno District, central Seoul. One day, a police officer suddenly burst in and said, “Would you please come with me for some questioning?” He was then escorted to the police station. It turned out that local residents and gallery visitors had reported to the police that his exhibition included “paintings extolling North Korea” — a criminal violation of the country’s national security law. During the Busan Biennale in 2008, his works on display were removed because they depicted the face of Kim Il-sung.

Song Byeok, another defector artist from the North, has gone through a similar experience. His paintings, including works depicting Kim Jong-il and Kim Jongun, were kept at his studio in a shopping mall in Gangnam, southern Seoul. Some elderly men who had seen these works complained to the authorities, which led to a visit by a National Intelligence Service agent.

“Self-portrait” by Sun Mu, 2009, oil on canvas, 100cm x 40cm. A note scribbled on the painting says, “Now it’s about 10 years away from you. I wonder when your door will be opened.”

No Lines, No Borders

Sun Mu slipped out of North Korea in 1998 and arrived in South Korea in 2002, after roaming around China, Thailand, and Laos. He is known as the first North Korean defector artist in the South. Unlike others, he did not flee the North because he disliked the regime. When young, he was a member of the Korean Youth Corps. He attended an art college for three years and served as a propaganda artist in the army. He fled the North by happenstance. He was temporarily working odd jobs for a living in China, when an election day in the North approached. It is mandatory for all citizens in the North to participate in every election. Anyone who fails to vote can be condemned as a political offender and sent to a concentration camp. But he realized it would be impossible for him to return to his home in Hwanghae Province, a region far from the North Korea- China border, in time for the election. Then and there, he decided not to return to the North. In all likelihood, this idea might have been percolating in his mind; he had been impressed by the affluent lifestyle in the South, which he came to learn about in China.

After arriving in Seoul, he enrolled in the College of Fine Arts at Hongik University, where he went on to complete his graduate studies, and became a profes- sional artist. He adopted the pseudonym Sun Mu (“No Line”) as an expression of his ardent hope that the border between the two Koreas would one day disappear. He never uses his real name or reveals his face in public for fear that his life here would cause harm to his family members in the North.

Sun Mu’s works are characterized by incisive criticism of the North Korean leadership and system. Bright and deceptively cheerful in a kind of pop art style that incorporates elements of North Korean propaganda art, his paintings are implicitly — and undoubtedly — subversive, as exemplified by “Kim Jong-il in Adidas” and “A Jesus in North Korea.”

His sardonic depictions of North Korean reality have caught the attention of international art communities, which has enabled him to stage several solo exhibitions abroad — two in New York, two in Berlin, and one each in Jerusalem, Oslo, and Melbourne. He plans to participate in a group exhibition in France this year. Western media have introduced him as a “faceless artist,” taking note of his works lampooning the leaders he was raised to worship as gods.‘I Am Sun Mu’In many of Sun Mu’s recent works, aspects of life in both Koreas, of people and things or events, are depicted side by side, as parallels. This reflects his fervent desire to help bring about peace, reconciliation, and coexistence. He takes a look at the peculiar circumstances of national division and the reality in the North through the lens of artistic inquiry, while keeping a distance from political propaganda. He doesn’t want to fall victim to ideology ever again, he says.

To fully understand Sun Mu’s works, one needs to get beyond simplistic interpretation. This is because he expresses his personal experiences and emotions on canvas while suffering from ideological confusion between two political systems that are poles apart. Although 14 years have passed since he first arrived in the South, he still finds it difficult to adapt to various aspects of his new homeland.

Many a time, he still lives in the North in his dreams, only to awaken and find himself at a loss in his real-life circumstances in the South.

The documentary film “I Am Sun Mu,” which was shown as the opening work for the 7th DMZ International Documentary Film Festival, held in September 2015, offers a glimpse of the kind of person and artist that he is. The 87-minute documentary, produced by American filmmaker Adam Sjoberg, sheds light on his life and work, and what he wants to bring about through art.

The film shows scenes from his aborted exhibition that had been scheduled to be held at a gallery in suburban Beijing in 2014. On the opening day, the Chinese police blocked people from entering the gallery. His artworks, together with a large ad banner, were removed and confiscated, and are still stranded in Beijing. He had intended to convey the Korean people’s desire for national reunification through works rendered mainly in red, white, and blue — the colors of the national flags of the six member countries of the stalled negotiations for North Korea’s nuclear disarmament.

“In the Square” by Sun Mu, 2015, oil on canvas,160cm x 130cm

“I wasn’t going to attend the opening anyway for security reasons. When my exhibition was called off, I was really afraid that I might be taken away, leaving my wife and two daughters behind,” he said.

In spite of many difficulties that he encounters as a marginal man, Sun Mu’s eyes are always looking out toward an open world. “When I visited New York for my exhibition, I realized that there are numerous different countries, including those in the Middle East, Africa, Latin America, and Europe, as well as the two Koreas, in the world. I want to create works about the lives of people in those lands,” he said.

via KOREANA

탈북 화가 선무, “그림은 나를 위한 프로파간다”

탈북 화가 선무는 얼굴 없는 작가다. 북한 출신 예술가 중에서 가장 주목받는 작가이지만 얼굴을 공개하지 않는다. 북한에 있는 부모형제에게 피해가 갈까 봐 걱정해서다. 단순히 탈북자이기 때문만은 아니다. 그의 작품은 사회주의 프로파간다 예술을 패러디한 팝아트 작품이다. 김일성·김정일·김정은 3대를 풍자하는 내용이 주를 이룬다. 조심스러울 수밖에 없다.

올해 DMZ국제다큐영화제 개막작인 <나는 선무다>는 그에 관한 영화다. 지난해 그가 베이징에서 전시회를 열었을 때 겪었던 일을 중심으로 그의 예술 세계를 다뤘다. ‘선무’는 ‘선이 없다’는 의미의 예명으로, 예술에는 경계가 없다는 그의 예술철학을 대변한다. 그러나 그는 베이징 전시회 과정에서 분명 예술에 경계가 있다는 것을 체험했다. 영화는 긴박했던 전시회 전후를 담았다.

|

||

|

ⓒ시사IN 조남진

1998년에 탈북한 화가 선무는 북한에 있는 부모형제에게 피해가 갈까 봐 ‘얼굴 없는 작가’로 활동 중이다. |

||

북한에서 미술을 전공한 그는 군복무 중 선전물 담당 화가로 활동했다. 그래서 사회주의 프로파간다에 정통하다. 3년 동안 중국에서 탈북자 생활을 한 뒤 라오스와 타이를 거쳐 한국에 들어온 그는 미술대학에 들어가 그림을 다시 배웠다. 그리고 그린 사람이 김일성이었다. 그는 그 순간을 이렇게 회고했다. “붓을 들었는데 떨렸다. ‘내가 정말 이 사람을 그려도 되는 것인가’ 하는 생각이 들었다. 북한에서는 일반인이 함부로 김일성·김정일의 그림을 그릴 수 없다. 그림을 그릴 때 누군가 뒤에서 칼 들고 위협하는 것 같아서 계속 뒤돌아보았다. 그렇게 그림을 완성한 후 ‘내가 남쪽으로 왔구나’ 하는 걸 실감할 수 있었다.”

남쪽에서의 경험은 충격의 연속이었다. 미술대학 신입생 환영회에서 하는 야한 게임에 놀라고, 미대 교수와 강사들이 특별한 기법을 강요하지 않고 그리고 싶은 대로 그리라고 하는 것에 놀라고, 그렇게 뭘 그렸는지 모를 그림이 팔리는 것에 놀랐다. 그런 그가 가장 놀란 것은 예술가가 경찰을 대하는 태도였다. “사진작가 노순택씨와 2인전을 하는데 경찰이 찾아왔다. 그러자 노 작가는 ‘무슨 이유로 하는 조사냐. 영장 가지고 와서 조사하라’고 강하게 항의하며 돌려보냈다. 나는 북으로 다시 쫓겨나나 싶어 간이 콩알만 해졌는데 그 모습을 보면서 ‘저것이 남한인가’ 하는 생각을 했다. 암튼 큰 걸 배웠다.”

사진가 노순택과 선무의 독특한 ‘북한 프로젝트’

서울시립미술관의 특별전 ‘북한 프로젝트’에도 그의 작품과 노순택 작가의 사진이 동시에 전시 중이다(9월29일까지). 둘의 작업은 대비된다. 노 작가는 북한에서 남한의 모습을 보고 그는 남한에서 북한을 본다. “처음에는 노 작가가 북한 사진으로 남한을 이야기할 수 있다는 말이 이해가 되지 않았다. 나는 남북이 별개라고 봤다. 그냥 생각 없이 찍은 사진이라고 생각했다. 그런데 이제 공감이 된다. 나도 남한에서 북한을 볼 수 있게 되었다.”

1998년에 탈북해서 남한 사회에 어느 정도 적응했다고 생각한 그는 지난해 베이징에서 전시회를 추진했다. 그런데 전시회를 열었던 미술관이 개관하는 날 봉쇄되었다. 가슴에 김일성 부자 배지를 단 북한 사람들이 전시장을 둘러쌌고 중국 공안은 전시회 주최 측을 조사했다. 그는 남북 대립의 냉혹한 현실을 실감하고 돌아서야 했다. 그때 압류된 그림이 아직도 베이징에 남아 있다.

이렇게 가파른 삶을 살았지만 그의 그림에는 위트가 있다. 어떻게 보면 북한 사회를 비꼰 것 같지만 다르게 보면 남한 사회를 비튼 것 같기도 하다. 그는 자신의 그림이 바로 자신의 이야기이고 인생이라고 했다. “그림을 통해서 나는 숨어도 숨은 것이 아니고 나서지 않아도 나선 것이 된다. 이것이 예술의 힘이라고 생각한다. 북에서는 김일성·김정일 부자를 위한 프로파간다를 했는데 여기서는 나를 위한 프로파간다를 한다는 생각이 든다. 내가 세상에 하고 싶은 말을 그림으로 대신하려 한다. 그것이 내가 그림을 그리는 이유다.”

Via 시사IN

얼굴 없는 탈북화가, 북 선전화 비틀어 남북 지운다

지난해 7월 말 중국 베이징의 웬덴미술관(元典美術館), 탈북 미술가 선무(線無·44)의 개인전 ‘홍·백·남(紅·白·藍)’ 개막식은 아수라장이 됐다. ‘탈북인을 소환하겠다’는 북한대사관의 신고를 받고 중국 공안들이 들이닥쳐 작품 80여 점, 도록 1000부를 압수했다. 선무를 보러 온 한국의 미술계 인사들도 ‘전시장에 오지 마세요’ 다급히 스마트폰 사발통문을 돌렸다. 선무는 황급히 귀국했다.

국립현대·서울시립미술관 전시

수용소·김정일·강성대국 빗댄 작품

북한 그림·사진 전시장 바닥에 깔아

북에 가족 있어 이름·얼굴 감춰

작업대 위엔 남·북 소주 함께 놓여

1998년 배고픈 가족들에게 돈과 식량을 가져다 준다는 중국의 친척을 기다리다가 두만강을 건넌 게 영이별이었다. 중국·라오스·태국을 거쳐 2002년 한국에 들어왔다. 북한에서 미대생이던 그는 한국에 들어와 홍익대 회화과와 동대학원을 졸업했다. 중국에 갈 때마다 이름도 나라도 없이 고생하던 시절 생각이 났다. 그래서 베이징 개인전에 더 의미를 뒀다. “일주일이라도, 하루라도 멋있게 전시하자고…. 쉽지 않으리라 예상은 했지만 저렇게까지 무지막지하게 나올 줄은 몰랐다.” 12년이 지났지만 달라지지 않았다. 어디에도 그의 나라는 없었다. 선무는 가명이다. 북에 남은 가족을 생각해 얼굴도 이름도 가리고 활동한다. 선(휴전선)이 없어졌으면 하는 소망을 담아 ‘무선(無線)’이라고 이용백 작가가 지어준 이름을 뒤집어서 쓴다.

선무의 작업실. ‘나는 누구인가’ ‘나는 선무다’라는 그림에서 비애와 정체성 혼란이 보인다. [권근영 기자]

광복 70주년은 곧 분단 70주년이기도 하다. 이를 돌아보는 전시가 곳곳에서 열린다. 국립현대미술관 서울관의 ‘소란스러운, 뜨거운, 넘치는’, 서울시립미술관 서소문 본관의 ‘북한 프로젝트’ 등 주요 국·공립미술관 두 곳에서 동시에 초대받은 미술가는 선무가 유일하다. 서울관에 쏟아져 나온 270여 점 중 마지막으로 걸린 것이 바로 선무의 그림이다. 북한의 선전 포스터 형식을 본떠 소년 소녀가 일사불란한 군무를 선보이는 장면 아래 ‘우리는 평화를 원해요’라고 썼다. ‘우리가 평화로우려면 어찌해야 하는가’ 반문하는 듯한 이 그림을 화두처럼 안고 관객들은 전시장을 나온다. 서울시립미술관은 금기시됐던 ‘북한’을 아예 주제로 내걸었다. 북한 유화와 포스터, 우표, 그곳 사진이 대거 전시됐다. 선무의 작품은 그 사이, 바닥에 깔려 있다. ‘정치범 수용소’ ‘김정일’ ‘강성대국’ 등을 나무판마다 새겼다. 그걸 밟고 지나가야 북한 그림을 볼 수 있다.

철책선이 한강변을 두르고 있는 행주산성 인근 작업실에서 그를 만났다. 방마다 빨갛고 파란 그림이 걸려 있었다. 교복 입은 어린이들이 한껏 미소지으며 율동하는 그림 아래엔 ‘세상에 부럼(부러움) 없어라’라고 적었다. 행복을 가장하고 과장하는 어린이들의 한결같은 표정을 보면, 이곳의 미래가 오싹하다. 선무는 작업대 위에 평양 소주와 참이슬을 나란히 놓고 데생하고 있었다. “남과 북의 사람들이 앉아서 한잔씩 나누면 참 좋겠다. 대동강 맥주와 남한 소주로 폭탄주도 만들어 먹으면 얼마나 재미있겠나.” 퍽 단순한데 절절하다. 그가 살아온 삶의 궤적 그대로이기 때문이다.

뉴욕타임스·슈피겔·BBC 등 해외 언론의 인터뷰가 이어지지만, 그의 그림은 전시 때마다 환대와 박대 극단을 오간다. 2008년 부산 비엔날레에는 그가 그린 김일성 초상화가 철거됐다. 서울 전시 때는 주민 신고로 경찰이 출동했다. “나는 어느 한 편에 서서 이야기하는 게 아니다. 그동안 내가 어떤 조직이나 독재자를 위해 프로파간다를 해 왔다면, 이제는 나를 위한 프로파간다를 한다. 지구인이라는 생각으로 두 지역에 대해 이야기한다.” 남한에서 결혼해 낳은 두 딸을 보며, 자신의 어릴 적 모습 그리고 이제는 꽤 컸을 북의 조카를 떠올린다. 이 아이들이 북에 살았다면 어떤 모습일까. “예술계에서는 인간의 차별이나 높고 낮음, 계급 이런 게 중요치 않은 것 같다. 이 세상에 예술이란 장이 있고, 그 안에서 내 생각을 거리낌없이 이야기할 수 있다는 게 좋은 거다.”

작업실 천장엔 태극기와 인공기 그림이 서로 칭칭 묶인 채 천장에서부터 드리워져 있었다. “베이징 전시 오프닝 때 아이들이 이걸 푸는 퍼포먼스를 하려 했는데….” 겪어온 시간에 회한도 미움도 많겠지만 그의 눈은 미래를 향한다. “예술이 세상에 얼마나 영향을 줄지 모르겠지만, 나는 그림을 통해 세상을 바꾸고 싶다.”

권근영 기자 young@joongang.co.kr

◆선무(線無)=북한 태생. 1980년대 TV에서 김일성이 그림 그리는 아이들을 독려하는 장면을 보며 화가 꿈을 키웠다. 98년 탈북해 홍익대 회화과(2007)와 동대학원(2009)을 졸업했다. 2007년 노순택·선무 2인전 ‘우리는 행복합니다’(호기심에 대한 책임감 갤러리)를 시작으로 ‘세상에 부럼없어라’(갤러리 쌈지, 2008), ‘Korea Now’(상상마당 갤러리, 2009), ‘선을 넘다’(주한 유럽상공회의소 사무실, 2011) 등 여러 차례의 개인전을 열었다.

Via 중앙일보

월간미술 : SPECIAL ARTIST 선무

선무라는 작가는 우리 미술계에 상징하는 바가 크다. 이는 탈북자 신분인 그의 개인적인 상황에만 기인하는 것이 아니다. 남북 분단현실에서 그의 작업 하나하나가 갖는 의미가 오롯이 미학의 문법에 기반하여 읽히지 않기 때문이다. 올해는 광복 70주년을 맞는 해이기도 하지만, 분단의 씨앗이 잉태된 지 70년이 되는 해이기도 하다. 그의 또 하나의 이름 ‘선무(線無)’처럼 그의 작품이 어떤 테두리 없이 읽힐, 이 땅에 경계가 사라질 그날은 언제가 될까?

야구공에 유채로 남북한 국기의 요소를 표현했다

당대적 존재로서의 선무, 혹은 보이는 것을 통해 보이지 않는 것을 드러내기

김동일 대구가톨릭대 사회학과 교수

10여 년 전 선무를 처음 만났을 때 이런 작가가 있다는 사실이 그저 놀라울 뿐이었다. 그가 겪은 탈북작가에 대한 편견에는 내가 마치 그가 된 것처럼 함께 분노했다. 그때 우리는 어리고 여렸으며 필요 없이 신경질적이고 또 독했다. 이 글을 준비하면서 다시 만난 선무는 그때와 다르지 않았지만, 예술가로서는 더 과감하고 확신에 차 있었으며 인간적으로도 더 성장해 있었다. 나 역시 예술가들이 세상의 변화를 유도해야 한다는 확신은 그때보다 더 확고해져 있었다. 그 확신 속에서 선무는 이미 의미 있는 궤적을 그려가고 있었다. 선무는 예술을 통한 사회의 변화, 나아가 사회에 대한 변화의 요구를 예술이라는 통로와 수단을 통해 제기해나가고 있는 것이다. 어찌 보면 예술에 대한 사회의 요구는 거역할 수 없는 운명일지도 모른다. 물론 그 요구에 응답할 수 있는 예술가란 매우 한정되어 있고 선무는 그 요구에 적합한 방식으로, 그것도 매우 자기화한 방식으로 응답하는 데 성공하고 있다.

분단의 모순과 선무의 비극

선무에게 사회의 영향은 매우 개인적 비극의 형태로 나타났다. 그 비극은 조선 말의 혼란과 일제 식민지배, 그리고 끝내 6·25전쟁이라는, 한반도를 휩쓸고 지나간 민족의 모순과 분리되지 않는다. 선무는 자신의 의사와 상관없이 그 비극의 연속된 전개의 한가운데에 서게 되었다. 그는 남과 북이 첨예하게 대치하는, 그것도 시대착오적 권력 세습과 불가해한 우상화가 강제되는 한반도의 북쪽에서 태어났다. 북한 사회의 모순을 더는 감당하기 어려운 상황에 이르렀을 때 그는 ‘탈북’이라는, 분단사회에서 한 행위자가 할 수 있는 가장 극단적인 행위로 대응했다. 선무는 자신과 가족에게 가해지는 굶주림과 정당성 없는 폭력을 받아들이지 않았다. 그는 또 다른 꿈을, 또 다른 열망을 품었다. 탈북은 그 꿈과 열망을 실현하기 위한 시도였다. 흥미로운 점은 선무가 예술을 통해 탈북자 선무 개인의 험난한 경험뿐 아니라 분단과 냉전, 이산으로 점철된 한반도와 세계 정치의 모순을 그대로 형상화하고 있다는 사실이다. 선무에게 예술은 압도하는 사회적 모순에 대응하는 무기였던 것이다. 선무의 붓끝은 사회적 모순에 대한 미학적 대응의 가능성의 경계를 모색하고 있다. 당대 예술은 언제나 사회의 요구에 의해 정당화되었다. 예술 아닌 모든 것으로부터 이탈하고자 했던 모더니즘 예술의 경우에도 이 점은 예외가 아니었다. 예술의 자율성과 독자성은 산업화와 자본주의, 그리고 1, 2차 세계대전으로 인한 사회적 변화의 결과였다(특히 우리의 경우 추상미술의 도입은 이른바 ‘미군의 군홧발’로 상징되는 광복 이후 정치경제적 상황과 무관하지 않다). 그러한 예술과 사회의 관계 속에서 이 지리멸렬한 한국미술의 새로운 가능성을 모색한다면, 선무의 미학적 실천은 특별한 방식의 하나일 수 있다.

탈북자 대 예술가, 선무의 이중적 정체성

선무는 탈북자인 동시에 예술가이다. 이 점은 가장 분명하지만 가장 쉽게 잊혀지는 사실이기도 하다. 여기서 선무와 선무의 그림들에 관한 가장 흔한 오해와 혼란이 비롯된다. 즉 정치적 관점에서 그의 그림을 이해하는 것이다. 그가 탈북자인 것은 맞지만 그의 그림을 탈북자의 것으로만 치부하는 관점은 옳지 않다. 그의 그림들은 정치적 프로파간다(선동)를 뛰어넘는다. 선무는 예술가이며, 따라서 그의 그림은 당연히 예술로서 다루어지고 해석되어야 한다. 선무의 작품들이 예술로 해석되어야 하는 이유는 의외로 예술의 본질적 특성에서 기인한다. 예술은 인간의 가장 본질적인 소망을 형상화하는 가장 의미 있는 수단이라는 것이다. 선무의 그림은 인간의 간절한 소망을 담고 있다. 그 소망은 그 자신만의 개인적인 소망일 뿐 아니라 통일을 기원하는, 한반도의 모든 사람의 소망이다. 나아가 북핵을 걱정하고 세계 평화를 기원하는 모든 사람의 간절한 소망이기도 하다. 그의 작품이 미국과 독일을 비롯한 세계인의 관심을 받는 것도 그 때문이다. 오히려 그들은 여기 남한 사람들보다 더 간절하고 순수하게 한반도의 통일과 평화에 관심을 갖는지도 모른다(그의 작업들은 이미 슈피겔, 뉴스위크, 타임, BBC 등에 의해 심도 있게 소개된 바 있다). 정작 그의 작품을 민감하게 다루는 것은 한반도 내부의 상황이다. 그의 작품들이 전시장에서 철거되거나, 때로 관객보다 경찰이 전시장에 더 많은 경우는 10여 년 전이나 지금이나 다르지 않다.

보이는 것을 통해 보이지 않는 것을 드러냄

선무의 작업이 매우 특수한 미학적 실천인 또 다른 이유에 대해서는 보다 섬세한 비평적 분석이 요구된다. 선무는 오직 유능한 미학적 행위자들만 실천할 수 있는 정교한 미학적 방법론을 구사하고 있다. 이 미학적 방법론은 탈북자의 정치적 선동과는 명백히 구분된다. 선무가 구사하는 미학적 방법론의 핵심은 눈앞에 놓인 ‘기표’(記表, signifier)와 그가 부여하는 ‘기의’(記意, signified) 사이의 간극을 정교하게 재조직하는 작업이다. 예컨대 2007년 청와대 뒤편 부암동의 한 대안공간을 시끌벅적하게 만들었던 <조선의 신>은 겉보기에 위풍당당한 북한의 지도자(김정일)를 사실적으로 묘사한 것처럼 보인다. 그러나 사실 이 작품은 그를 경찰에 신고한 주민들의 우려에도 불구하고, 그들의 최고 존엄의 머리 위에 날카로운 별을 거꾸로 위치시킴으로써 시각적 비판을 가하려는 시도였다. 비슷한 상황은 2008년 부산비엔날레 전시장에서 철거되는 수모를 겪은 <조선의 태양>에서도 반복되었다. 겉으로는 김일성의 상반신을 북한식 선전화 방식으로 표현한 듯 보이지만 그 아래 놓인 꽃(김일성화)은 조용히 ‘NO’의 형태를 취하고 있다. 김일성, 나아가 그가 수립한 북한정권은 ‘아니’라는 것이다. 그는 단순히 화가라기보다는 시각적 기호학자로 볼 수 있다.

중의와 내포의 이중 해석학

그는 눈에 보이는 것을 눈에 보이는 그대로 제시하지 않는다. 오히려 눈에 보이는 것에 완전히 상반되는 의미를 부여한다. 이런 방식은 그의 초기작에서부터 지금까지 계속되고 있다. <우리는 행복합니다>는 더 이상 행복할 수 없는 북한 어린이들의 기쁨을 담고 있다. 그러나 그들의 기쁨과 행복은 도무지 자연 상태의 어린이로서는 가능해 보이지 않으며, 역설적으로 그러한 불가사의한 기쁨을 ‘강요’하는 인위적이고 강압적인 사회체제를 드러내고 고발하는 효과를 갖는다. 드러나는 것을 통해 드러나지 않는 의미를 내포하는 미학적 방법은 팝아트 양식을 차용한 작품들에서도 발견된다. 나이키 운동복과 아디다스 운동화를 신고서 익살스럽게 미소짓는 북한 지도자의 모습에는 자신과 자신의 가족들, 그리고 북한 동포 대부분을 가난과 굶주림으로 몰아넣은 폐쇄정책에 대한 비판과 그것을 극복하기 위한 개방 요구를 동시에 내포한다. 그가 자신의 작품이나 전시 제목으로 사용하는 “우리는 행복합니다”, “세상에 부럼없어라” 등의 표현 역시 단순한 선언이 아니라 부러움 없이 행복한 세상에 대한 간절한 소망과 그것을 불가능하게 만드는 한반도의 상황에 대한 근본적인 비판을 함축한다.

해방된 상상의 공간으로서의 예술과 소통

중의(重意)와 내포(內包)의 이중의미화(double signification)는 선무가 수행하는 미학적 실천을 단순한 정치적 수사로부터 분리한다. 선무가 분단과 탈북의 정치적 층위에 위치하는 것은 부정할 수 없지만, 그보다 더 분명한 것은 그가 예술가이며, 이 점은 그의 그림을 이해하려 할 때 생각보다 훨씬 중요하다. 오히려 화가로서 선무의 정체성은 탈북자로서의 그것보다 선행할 수 있다. 그는 탈북 이전에도 이미 화가였다. 예술가로서 선무는 선무를 선무이게 만드는 본질적 조건이라는 것이다. 흥미로운 점은 조국의 분단이 그에게 정치적 구속성을 행사한다면, 예술은 선무에게 그러한 정치적 구속으로부터의 ‘해방’을 가져다준다는 것이다. 예술은 본질적으로는 상상의 공간이라는 점에서 정치적 구속성으로부터 자유롭다. 또한 해방된 상상의 공간은 예술이라는 이름으로 자유로운 소통을 가능케 한다. 정치적 맥락에서 선무는 이편 아니면 저편에 서야 한다. 이러한 상황은 북에서나 남에서나 본질적으로 다르지 않을 것이다. 그러나 예술이라는 해방된 상상력의 공간에서 그는 그 어느 일방을 옹호할 필요가 없다. 해방된 상상의 공간에서 선무는 민족의 통일과 행복에 대한 보다 근본적인 소망을 정치의 구속으로부터 벗어나 자유로운 방식으로 전달한다. 분단과 굶주림을 극복하고 행복한 한반도, 평화로운 세상으로 나아가고자 하는 선무의 요구는, 소중한 가족을 북에 두고 온 선무 자신의 개인적 소망일 뿐 아니라 남과 북을 막론하고 같은 소망을 갖는 지구상의 모든 사람과 나눌 수 있는 보편적인 메시지가 된다.

광복 70년 그리고 선무

이러한 해방된 상상력과 자유로운 소통의 조건은 저절로 주어지는 것이 아니라 자신이 그려온 정치적 궤적과 미학적 궤적을 서로 교차하는 방식으로 재구성하는 선무 자신의 성취라 할 수 있다. 선무에게는 미안한 일이지만 한국 현대미술의 현장 속에서 선무는 대단히 반가운 존재이다. 그의 비극은 그 자신에게는 형용할 수 없는 아픔이지만 그가 그 아픔을 형상화하고 극복해 나가는 과정은 예술과 사회의 관계라는 지평 속에서 새로운 가능성을 제공하는 것이 사실이다. ‘광복 70년’은 단순히 해방 이후 시간의 총량을 의미하는 것이 아니다. 그것은 한반도의 과거의 질곡을 극복하고 현재의 상황과 미래의 가능성을 전망하려는 의지의 표현이다. 광복 70년의 시대적 요구에 예술이 대응해야 한다면, 그 가능성은 선무의 작업을 통하지 않고서는 유의미하게 논의되기 어렵다. 그만큼 선무라는 개인, 그리고 그의 미학적 대응은 모두 당대적 의미를 획득하고 있기 때문이다. ●

선무 Sun Mu

선무는 1972년 황해도에서 태어났다. 홍익대 미술대학 회화과와 동 대학원을 졸업했다. 2008년 첫 개인전을 열었으며 한국을 비롯해 멜버른, 뉴욕, 베이징 등지에서 12회의 개인전을 열었다. 또한 한국과 독일에서 열린 다수의 기획전과 그룹전에 참여했다. 현재 경기도에서 작업하고 있다.

서울시립미술관 <북한프로젝트전> 전시광경 바닥 설치작업은 <평양의 자유>와 <우리 식대로> 나무판에 유채 30×25×2cm(각) 2011

interview

“나 자신을 어떤 것에 가두고 싶지 않다”

작품에 등장하는 인물 묘사가 매우 직접적이다. 예컨대 정치 지도자가 그렇다. 그런데 그들이 등장하는 작품 메시지가 매우 직접적이라면 아이들이 등장하는 작업은 어떤 희망(예를 들면 통일된 세상이나 보다 나아진 남북관계, 정치적 상황 등)을 비유하고 있다고 본다. 한반도의 지도자라고 하는 사람들, 특히 북녘에 있는 지도자들을 보면서 오직 권력을 위해 백성의 삶은 안중에도 없는 통치를 일삼고 있으니 이는 분명히 잘못됐다는 생각을 했다. 나는 아이들을 통해서 우리들의 미래를 이야기하려 한다. 작품에 무엇이 나오든지 간에 남과 북의 허무하고 쓸데없는 이념대결이 낳은 죽음에 대한 안타까움을 이야기하려 한다.

그야말로 남북이 처한 정치적 상황의 딱 중간, 경계에 서있다는 느낌이 들었다. 작가로서, 정치적인 상황이 판이한 두 곳에서 생활해본 시민으로서 경계에 대한 생각과 느낌이 특별할 것이다. 몇 년 전에 재독동포 송두율 교수의 글을 읽을 기회가 있었는데 그분의 생각이 나랑 많이 비슷한 것 같더라. 나 역시 경계에서 이쪽과 저쪽을 바라보면서 무엇이 서로에게 도움이 되고 상처가 되는지를 알기에 경계에서의 역할이 중요하다고 생각한다. 경계, 중간에서 역할은 여러 가지가 있을 테지만 예술의 역할도 중요하다. 예술이야말로 경계에서 자유롭게 비판하고 구애받지 않고 미래를 이야기할 수 있는 장이고 그 속에 내가 있다는 사실을 매우 감사하게 생각한다.

어떻게 보면 우리 미술판에서 작가 선무는 분단 현실의 상징적인 인물일 것이다. 그런데 그것이 분단 현실 때문이기도 하겠지만, 남한에 정착하면서 생겨난 또 다른 종류의 한계일 수도 있겠다는 생각이 들었다. 글쎄. 이 세상에서 선무라는 존재가 어떻게 불릴지는 더 두고 봐야겠다. 분명히 남과 북은 서로 다른 체제로 반세기 넘게 살아왔고 나라 이름도 서로 다르다. 하지만 외국 사람들은 좀 다른가 보다. ‘북코레아, 남코레아(north Korea, south Korea).’ 이게 다다. 여기에 조선은 뭐고 대한민국은 뭐냐 이거다. 이데올로기 전쟁으로 입은 상처는 남과 북이 고스란히 가지고 있고 치유되지도 못했는데. 랭전은 끝났다고 하지만 여전히 존재하는 허무한 이념대립. 이런 것을 보고 듣고 느끼면서 한심하다는 생각이 든다.

‘국경을 넘기 전 바라봤던 중국령 지역과 경계를 넘고 바라봤던 북한령 지역’을 떠올린 말은 가슴 저릿했다. <국경선>(2007), <두만강>(2007, 2008), <어디가 동쪽이냐>(2005) 등은 국경을 넘기 직전 작가의 상황을 잘 드러내는 작품으로 보인다. 가만히 앉아서 잡혀 죽느니 내 갈 길 가다가 죽어야 후회 없을 것이란 생각에 무작정 남쪽으로 가기 위해 노력했다. 죽음을 각오하고 세상과 마주하니 두려울 것이 없었다.

탈북 후, 중국에서 이른바 ‘낭인(浪人)’처럼 지냈다고 했는데 그때 경험이 바탕이 된 작품을 찾아보기 힘들다. 이유가 있는가? 이유가 있다. 실제 인물들을 작품에 담기가 조심스러워서다. 지금도 나고자란 마을을 그리지 않는다. 혹시나 모를 이념 전쟁에 희생양이 되거나 불행해질 수도 있기에 아직은 미루고 있다. 물론 스케치는 생각나는 대로 해두었지만 나중을 기약하고 있다.

남쪽에 정착해 이런 저런 현상을 목격하면서 그간의 생각이 많이 바뀌었을 것이다. 가장 많이 바뀐 생각은 무엇이며, 그것이 드러난 작품은 무엇인가? 가장 인상 깊은 사건은 광화문 초불(촛불)시위였는데 광우병 쇠고기 수입 반대 시위 현장을 직접 보고 느끼려고 광화문 네거리에 직접 나가 보았다. 광화문의 초불을 보고 김일성광장의 회불(횃불)을 떠올렸다. 많은 생각이 들었다. 가족이 나와 앉아서 평화적으로 자신들의 의사를 표현하는 광경은 참 아름답기까지 했다. 그래서 종이를 칼로 오려서 <초불>이라는 작품을 하기도 했다

작업은 정치 상황을 희화화(유머러스하거나)한 듯하다가도 분단의 엄혹한 현실이 섬뜩하게 드러나기도 하고, 현 상황에 대한 시사적인 내용이 직접적으로 드러나기도 한다. 말 그대로 다채롭다. 그 이유는 간단하다. 뭘 모르니까. 보통 예술이라는 장에도 여러 방법, 방식이 있고 의도적으로 원하는 방법과 방식을 따라 할테지만 그런 저런 지식이 없으니 생각 나는 대로 막 할 수 있었고 그럴 수 있다고 본다. 나의 생각을 어떤 식으로 표현할지 생각하고 그냥 하는 것인데 주변에서 이것을 정리해 팝아트라 불러주더라. 하지만 이 또한 잘모르겠고 알고 싶지도 않다. 나 자신을 어떤 것에 가두고 싶지 않다.

“나는 끝까지 조선사람으로 남겠다”는 생각으로 남한행을 결심했다고 했다. 그렇다면 앞으로 작가로서 활동하면서 변화하는 남북관계에 따라 무엇인가 할 일, 이른바 소명(召命)이 생길 것으로 보인다. 그것은 무엇일까? 남쪽에 와서 처음 전시를 시작하면서 어떤 사명감 같은것을 가지고 살았다. 그런데 그 사명감이 뭐냐. 어떤 철학교수가 말하기를 사명감 또한 이데올로기 아니냐고 하더라. 그래 나는 나로서 산다, 나는 누구냐, 뭘 하는 놈이냐, 내가 나로서 당당히 살아갈 때 가치가 있다. 이제는 조선 사람도 좋지만 지구인으로 살려한다. 조그만 지구에 살면서 서로 싸우고 죽이고 편 나누고 아주 그냥…,

앞으로 전시계획, 작업계획에 대해 알려달라. 올해 국립현대미술관과 서울시립미술관에서 여는 분단에 관한 전시에 참여한다. 내년에는 홍대 주변에서 개인전을 열 생각이다. 작업은 계속 해서 사람 사는 세상과 한반도의 비극과 미래를 이야기하려 한다.

황석권 수석기자

Via 월간미술